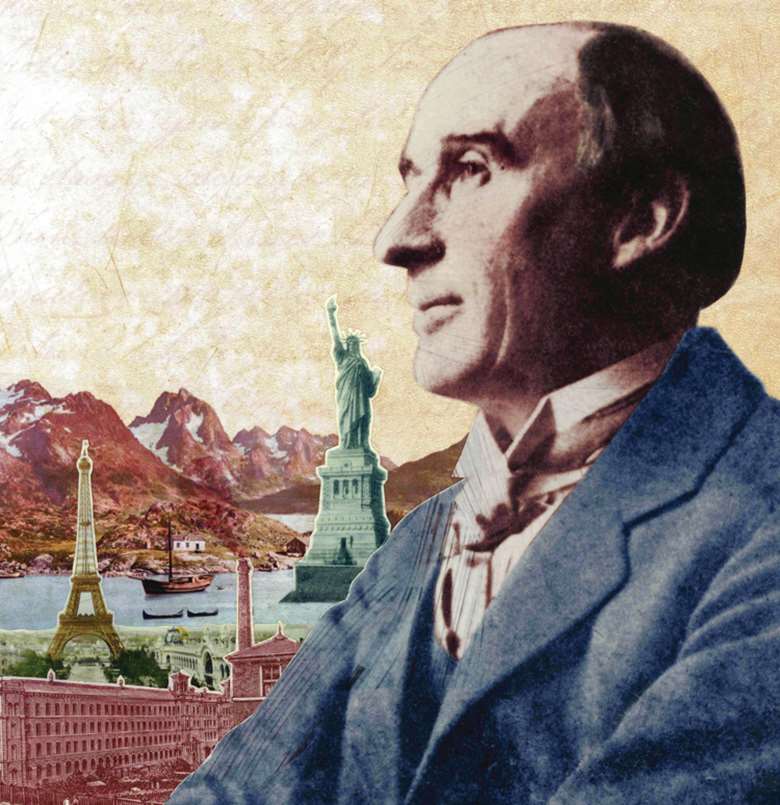

Frederick Delius – the cosmopolitan composer

Jeremy Dibble

Thursday, January 29, 2015

Delius was a truly international voice in an increasingly nationalist age. Jeremy Dibble traces the composer’s travels and the works that resulted

Born in Bradford on January 29, 1862, Fritz Theodor Albert Delius was, by birth, an Englishman, even though his immediate heritage, as the son of parents from Bielefeld, was German. Yet, if we are to define Delius in terms of his colourful life, his cultural purview, his wide interests, his wanderlust and, most importantly of all, his musical voice, then the task of placing him geographically remains problematic in an age when one of the most significant and dynamic factors in musical composition, and in Western culture in general, was nationalism and national identity.

More than 150 years after Delius’s birth, a new European polity may have brought a different perspective to the old nationalist fervours but our perception of musical history of this epoch is still powerfully informed by national styles – French, German, Russian, Italian, Czech, Polish, Norwegian, even English – yet the music of Delius fails to fall happily into any national category. In fact, it’s Delius’s eclecticism, his receptiveness to a wide range of cultures, and the very resistance his musical style demonstrates towards established models and stereotypes (and this includes his maverick approach to musical syntax, form and tonality) that makes him such an elusive figure. At the same time, his highly individual harmonic language, derived largely from Grieg, yet overlaid with the influences of Wagner, Strauss and Debussy, is unlike any other, and is conspicuously personal and immediately recognisable to the ear. Indeed, Delius’s very elusiveness has rendered him something of a controversial figure, for his style – a kind of musical Marmite – seems, on the whole, to engender extreme polarities of opinion, attracting followers of immense fervour and devotion (a group to which I count myself), or detractors who feel listless in their revulsion. The music of Delius, for some, exudes an irresistible perfume and has the power to evoke a sense of deep nostalgia and longing; for others, there will always be a profound association with nature and landscape. Yet, while Delius’s music may have a beguiling pastoral aspect – one that sought to illustrate the varying landscapes of Scandinavia, the American tropics and even perhaps the English north country – this is only one side of a much broader personality which embraced the music of the black Americans of the deep south, the Weltschmerz of poets such as Whitman, Jacobsen, Bjørnsen, Verlaine and Ernest Dowson, and Nietzsche’s obsession with the dance of life.

The seeds of Delius’s wanderlust were sown in one sense by accident, and in another by his innate sense of rebellion. His father, Julius Delius, by all accounts a martinet who ruled the home with a rod of iron, was determined to see his sons follow him into the wool business. This industry, which prospered in the Yorkshire industrial conurbations, had rewarded him with wealth and local influence, and this he naturally wished to pass on to his male children. Ernst Delius, the oldest son, left England to try his hand at sheep farming in New Zealand, leaving Fritz [he later anglicised his name to Frederick] as the natural successor. Mutiny was probably maturing in Fritz’s mind when, after his formal education at Bradford Grammar School and the pioneering International College in Isleworth (which promoted a liberal international education in business acumen and free trade), he entered the workplace in his father’s factory in 1881 but, thanks to Julius’s quick wits, he saw to it that Delius’s abilities were exploited more profitably as a travelling agent in Europe. This gave rise to a series of largely (though not totally) unproductive yet serendipitous sales excursions to European locations which would prove entirely providential to the impressionable would-be composer.

In 1881 Delius found himself in Chemnitz, the third largest city in Saxony, which was not far from Dresden, Berlin to the north, Weimar and Jena to the west, and Leipzig to the north-west. The presence of the violinist Hans Sitt made it possible to continue his studies on the violin, and there was the revelation of Wagnerian opera in the form of Die Meistersinger in Dresden. Such experiences inevitably led Delius to lose sight of the real reason for his German expedition. In 1882 a trip to the Swedish centre of the clothing industry in the municipality of Norrköping, in the south-east of the country, began more promisingly, but commercial interests were soon forgotten again as he became infatuated by the wondrous scenery of rural Sweden and even more so by the Norwegian fjords and mountains (as well as acquiring a certain facility for the languages of both countries). An irritated and frustrated Julius Delius, conscious of his son’s propensity for artistic distraction, decided more strategically to send him to St-Etienne in France, a location where cultural temptations were less accessible. Delius loathed it and, in defiance of his father, hastened to Monte Carlo, gambled his money – with positive results – and enjoyed the delights of the Riviera replete with more opera visits, concerts and violin studies. On being recalled to Bradford, Delius also took the opportunity to visit his father’s brother, Uncle Theodor, in Paris, which, with its concentration of salons, artists, poets and composers – ultimately the most lively European musical centre of the time – stoked the fires of paternal resistance even more fundamentally. Yet, as Thomas Beecham remarked, in spite of these repeated setbacks, an irate Julius ‘remained undefeated’. Fritz, for his part, eager to mollify his exasperated father, persuaded him that he might find success growing oranges in Florida. Hence, with a companion, Charles Douglas, Delius sailed for America in March 1884.

America

Delius spent in total just over two years in the United States. In north-eastern Florida, he resided in a shack at Solana (known today as Solano) Grove on the St Johns River, about 45 miles from Jacksonville (where, at the University, it has been preserved since 1961). It turned out that he had no more propensity for growing oranges than he did for selling wool but, like on so many occasions in Delius’s life, he had the knack of turning experiences and encounters to his advantage. In the tropical Floridian creeks, he would shoot alligators with the locals, and at night enjoy the sound of their distant choral improvisations and spirituals – an ambience, he always claimed, that supplied the initial impetus for him to become a composer. Furthermore, a chance meeting in Jacksonville with a New York organist, Thomas Ward, enabled him to learn the rudiments of harmony, counterpoint and form. After only a year and a half, and with a musical career planted firmly in his mind, Delius abandoned all notion of orange-growing and set up as a music teacher in the more fashionable Virginian town of Danville. Here he was, to the delight of his father, financially successful. But Danville was not big enough to accommodate Delius’s more ambitious vision for himself. He moved to New York, and when Julius agreed to fund 18 months at the Leipzig Conservatory – with a view to his son possibly continuing his musical profession in the US – Delius set sail for England in June 1886. Much against the wishes of his family, he did not pursue a musical career in America, but he did return to Florida in 1897, probably to see if his deteriorating property could be rented out or sold off.

The effects of Delius’s time in America manifested themselves at Leipzig when, as a student, he composed Florida in 1887, a suite for orchestra which, in the published score, he dedicated gratefully ‘to the people of Florida’. Performed privately in 1888 in Leipzig at the restaurant Rosenthal under Hans Sitt’s direction, it was not heard publicly until 1937, when Beecham conducted three movements of the suite at Queen’s Hall. A vibrant, atmospheric piece, Florida (subtitled in German in the manuscript ‘Tropische Szenen für Orchester’) contains many of those essential ingredients of Delius’s musical persona: bold modulations, an affinity for landscape and nature (notably in ‘Daybreak’ and ‘Sunset’), a delicate orchestral palette full of characteristic woodwind filigree and, through his continuing assimilation of Grieg, a musical language heavily influenced by the harmonic originality of the Norwegian composer. Florida also looked forward to later compositions. Its third movement, ‘Sunset’, which, in the original manuscript, also contains the description ‘Bei der Plantage’, evokes a Negro spiritual that is strikingly close to ‘I got plenty o’ nuttin’’ from Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. The American ambience is palpable and almost like nothing else he composed.

Material from the first and fourth movements Delius later employed in his second opera, The Magic Fountain of 1893, the plot of which is based on the discovery of Florida in 1513 by Ponce de León. Sadly this intriguing and inventive score has only been recorded once, by Norman Del Mar, the BBC Concert Orchestra and BBC Singers with John Mitchinson and Katherine Pring (BBC; 11/87 – nla), and is much in need of a modern performance. The latter part of the first movement of Florida also includes the famous Delius ‘lollipop’ ‘La Calinda’, which, like various passages from The Magic Fountain, was used in another American opera, Koanga, completed in Paris in 1897. Based on The Grandissimes: A Story of Creole Life by the American novelist George Washington Cable (published in New York in 1880), the setting is a sugar cane plantation on the Mississippi River in Louisiana during the second half of the 18th century. The story focuses on a handsome new slave, Koanga – an African prince and voodoo priest – and Palmyra the mixed-race maid. Sounds of distant slave choruses and the addition of banjo (again foreseeing Porgy) add to the tropical impression, and the wedding music, which incorporates ‘La Calinda’, is enormously buoyant. Yet the plot concludes in bloody violence with the death of Koanga and Palmyra’s suicide, leaving the opera to end in the disturbed tranquillity of the Epilogue.

Other American resonances appear in the tone-poem Hiawatha, also a student work, and in Delius’s other early Suite d’orchestre, written in 1889 and 1890 and which (in terms of subject matter) contains a prophetic reference to Koanga in the movement ‘La Quadroone’ (quadroon meaning someone of mixed race – specifically a quarter black). But the climax of Delius’s spiritual affinity with America, and especially with the tropical landscape of the Mississippi, has to be his two orchestral essays both entitled Appalachia. The first, conceived as an American Rhapsody in 1896, makes reference to the civil war songs ‘Yankee Doodle’ and ‘Dixie’ as well as an old slave song. The latter is then deployed in a second, more extended work in 1902, where the slave song, worked up into an impressive and unconventional symphonic set of variations, is heard in a sonorous choral form at its conclusion.

Norway

It was essentially his love of nature and high, lonely places that drew Delius to the Norwegian mountain ranges of the Jotenheim (known today as Jotunheimen) in 1882, but his encounter with Norway (and Denmark) gained much greater momentum after he began his studies in Leipzig. There, most of his friends were Norwegians such as the composer Christian Sinding and two young violinists, Arve Arvesen and Johan Halvorsen. Even more importantly, Delius’s assimilation of Norwegian music and literature occurred at a crucial juncture when a growing sense of nationalism was propelling Norway towards independence in 1905. Delius spent his first summer vacation in Norway in 1887 (he kept a diary) and, through the agency of Sinding, was introduced to Grieg (who was in Leipzig to study orchestration) during the autumn semester of that year. Lionel Carley’s book Grieg and Delius: A Chronicle of their Friendship in Letters details the extent of the correspondence between the two men, and between Delius and Nina Grieg after Edvard’s death in 1907.

Grieg, for his part, recognised Delius’s gifts from the beginning: ‘I was pleasantly surprised…by your manuscripts [probably Florida and Hiawatha] and I detect in them signs of a most distinguished compositional talent in the grand style,’ he wrote to Delius on February 22, 1888. Grieg was also signally important in persuading Delius’s father to allow Delius to continue his musical studies in Paris after he had left Leipzig in 1888. In 1889 Delius paid his first visit to Grieg’s home at Troldhaugen; it was to be the first of many visits to Norway and Denmark during the 1890s. After a break of seven years, his visits resumed in 1906 and were regular until 1915. The disruption of the war delayed any further visits until 1919 when, in spite of the expense of travelling and accommodation, he returned to Norway; the country continued to lure him for the summers of 1921, 1922 and 1923. After this, owing to his encroaching illness, he was too weak to make the journey again, a tragic scenario captured in the late Ken Russell’s documentary as the paralysed Delius, on the point of losing his sight, is carried up the mountain by Grainger and Jelka, his wife, to see the sun set for the last time.

Germany

Delius was always scathing about how much he genuinely learnt from his time at the Leipzig Conservatory but, in truth, he is likely to have gained a great deal from the rigorous exercises in harmony and counterpoint with German teacher-composer Salomon Jadassohn – exercises which would have brought a discipline to the largely rudimentary work initiated with Ward in America. Moreover, the sheer availability of live music at the Gewandhaus and at one of the best opera houses in Germany could not have failed to invigorate and enrich Delius’s vocabulary and technique, a fact borne out by the impressive accomplishments of Florida, Hiawatha, Sakuntala and Paa Vidderne. But where Germany proved to be vital was through the receptivity of German audiences and conductors to Delius’s music and the readiness of German publishers to disseminate his works (a factor which led to many of his major works being printed and performed in German). Though his appetite for Grieg never wavered, during the 1890s Delius’s hunger for modern German music grew significantly.

He visited Bayreuth and Munich in 1894 and avidly ‘consumed’ Wagner’s Parsifal, Tannhäuser, The Ring, Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger, whose orchestrally driven conceptions undoubtedly inspired pages of Koanga and A Village Romeo and Juliet (1900-01). And later in the decade, when the music of Richard Strauss was sweeping across Europe, Delius could not help but be infected by the innovative, luscious canvases of Don Juan, Tod und Verklärung, Till Eulenspiegel, Also sprach Zarathustra and Ein Heldenleben with their opulent orchestrations and gripping programmatic designs. His fascination for Strauss’s tone-poems gave rise to Paris: A Nocturne (The Song of a Great City) of 1899 and Lebenstanz (and its earlier version La ronde se déroule) of 1901. Lebenstanz also betrayed another of Delius’s growing obsessions: the literature and poetry of Friedrich Nietzsche. Strauss’s tone- poem had already done much to bring Nietzsche before the musical public, and although Delius believed the work to be a failure, he became increasingly absorbed by the German’s philosophical standpoints, particularly with the image and metaphor of ‘life’s dance’. This aspect was clearly responsible for the plethora of ‘dance episodes’ that populate his scores and which are epitomised in the two Dance Rhapsodies.

Delius’s first major essay on a Nietzschean theme, for baritone, male chorus and orchestra, was Mitternachtslied Zarathustras of 1898, arguably one of the pivotal works between Delius’s period of artistic self-communion and his full maturity as a composer. This choral movement was later bodily relocated to A Mass of Life, completed in 1905, the composer’s most extended Nietzschean choral work. Besides being one of his greatest and most original achievements, it is a work that largely embodies his own artistic and philosophical outlook. Moreover, when sung in German, the Mass seems to possess extraordinary parallels with other contemporary current works by Schoenberg (his Gurrelieder of 1901) and Zemlinksy (even his much later Lyrische Symphonie of 1922-23), such is the modernism of its language and content. It was an impression confirmed by the young Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály after they heard the work in Vienna in February 1911 and which caused Bartók to produce an article on Delius’s use of the wordless chorus for the music journal Zeneközlöny in Budapest.

Ultimately, however, it was Germany that first gave recognition to Delius’s genius as a composer and for this we have to acknowledge the openness and enterprise of Hans Haym and Fritz Cassirer at Elberfeld, Julius Buths in Düsseldorf and Nikisch at Leipzig. Haym directed performances of Over the Hills and Far Away, Paris, the Piano Concerto, Appalachia and the first complete performance of A Mass of Life; Cassirer premiered Koanga at Elberfeld in 1904 and A Village Romeo and Juliet (Delius’s only opera to be based on a German-language novella) at the Komisches Oper, Berlin, in 1907, while Buths conducted major performances of Appalachia, Paris, the premiere of Lebenstanz and the Piano Concerto. Busoni, who was well acquainted with Delius, also directed a performance of Paris in Berlin in November 1902. As for Delius’s other great choral masterpiece, the hauntingly melancholy Sea Drift, a setting of Walt Whitman for baritone, chorus and orchestra, this was first given in May 1906 at the Essen Tonkünstlerfest under the aegis of the Allgemeine Deutsche Musikverein; the conductor was Georg Witte.

England

Although Delius is known to have been openly critical of English music and its environment, he nevertheless constantly looked to England as a place where his music could be performed and enjoyed. A concert of his music in London on May 30, 1899, under the baton of Alfred Hertz, was widely and enthusiastically reviewed (it included La ronde se déroule, movements from Folkeraadet, Mitternachtslied Zarathustras, the Légende for violin and orchestra, excerpts from Koanga and Over the Hills and Far Away), but it was not until well into the next decade that performances of his music began to exceed those of Germany. Henry Wood took an active part in this process, though of course it was the significant meeting of Delius and Beecham in October 1907 at Queen’s Hall that guaranteed the future of Delius’s music in the country of his birth.

Delius’s acquaintance with other English musicians also flourished at this time, notably with Bantock, Australian-born Grainger (whom he first met in April 1907), Elgar, Norman O’Neill and Balfour Gardiner (who generously purchased the house at Grez-sur-Loing on the Deliuses’ behalf). Delius was closely involved in the short-lived Musical League in 1909 (as its vice president) in an attempt to promote new British music, though in retrospect the amount of time spent on this project was disproportionate to the results. He was also a major inspiration (and unsuitable mentor) to the young Philip Heseltine (Peter Warlock), Delius’s first biographer, whose life was changed by hearing the part-song ‘On Craig Ddu’ as an Eton schoolboy in 1911.

Much of Delius’s later music ultimately found its home in English concert halls. A somewhat eccentric and unsuccessful conductor of his own works, Delius directed premieres of In a Summer Garden and A Dance Rhapsody (No 1) in 1908, the same year as Bantock first produced Brigg Fair at Liverpool (perhaps Delius’s most ‘English’ work, based on a Lincolnshire folksong provided by Grainger). The Songs of Sunset (1906-08), a notable setting of English poems by Ernest Dowson, was first performed under Beecham in London in 1911, and other major premieres followed including the Double Concerto for violin and cello (1915), written for May and Beatrice Harrison, the Violin Concerto (1916) composed for Albert Sammons, the North Country Sketches (1913-14), the unequal Requiem (1914), The Song of the High Hills, given in 1920, and A Dance Rhapsody (No 2, 1916), which Wood conducted at Queen’s Hall in October 1923.

It was also, of course, a fellow Yorkshireman, Eric Fenby, who came to Delius’s aid in 1928 as amanuensis, and helped bring into existence new or unfinished works such as Cynara (drafted 1907, completed 1929), A Song of Summer (also 1929), a major revision of the Poem of Life and Love (1918-19), recently recorded for the first time, the Third Violin Sonata (1930) and his final setting of Whitman, the Songs of Farewell (also 1930). Such was Beecham’s devotion to Delius that he also organised the Delius Festival in 1929, a tribute to an English composer not seen since the London Elgar Festival at Covent Garden in 1904 under Hans Richter (who, incidentally, had a loathing for Delius’s music). It was to Beecham that a contented Delius attributed the honour of his Order of Merit that same year. ‘I wish you,’ he wrote to Beecham, ‘who so thoro’ly understand my music and who are the one authority as to how it should be played – would re-edit my music as you are planning.’ It was a task that Beecham, who organised a further Delius Festival in 1946, gladly undertook.

France

When Delius moved in with his Uncle Theodor in Paris in May 1888, he probably had no idea that he would make France his permanent home. Renting accommodation both in and outside Paris, he was enamoured by the French capital and everything artistic it offered, an impression evoked by the vivid and diverse episodes of his tone-poem Paris, surely one of his most autobiographical essays. Without the stimulus of Paris’s salons and concert halls – where he met, among others, Gaugin, Edvard Munch and Florent Schmitt (who produced vocal scores of several of Delius’s operas) – Delius might never have experienced the freedom to discover his creative self. Yet, for all his interaction with French cultural life, his works reflect arguably little of that country’s music or language. Only one dramatic work in French survives – the one-act opera Margot la rouge, a lyric drama dated 1901-02 (the vocal score was prepared by Ravel). Entered for the Concorso Melodrammatico Internationale of 1904, it failed to win a prize; only after Fenby arrived at Grez did Delius exhume the work and reshape it into the Idyll: Once I passed through a populous city.

Earlier, in 1896, Delius had met Jelka Rosen, a painter who worked in Paris and Grez-sur-Loing (one of three villages along the Loing river due south of Fontainebleau). Rosen moved permanently to Grez in 1897 and Delius joined her after returning from America. The couple then remained in Grez (they formally married in 1903). Here, Delius spent months in contemplation and composed most of his greatest works. It was a quiet spot, with a spacious garden that led down to the river. Works such as In a Summer Garden and the two miniatures for small orchestra, On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring and Summer Night on the River, are perceived as embodying the essence of English pastoralism but perhaps the Corot-like French landscape scenes surrounding him were more responsible for nourishing his creativity.

In his last years at Grez, both Delius and Jelka were largely isolated except for the presence of Fenby. They enjoyed visits from friends and admirers, though, among them Warlock, Grainger, Patrick Hadley and, in 1933, Edward Elgar.

Delius died at Grez on June 10, 1934, and was temporarily interred in the village churchyard. In 1935, however, in accordance with his wishes, his final interment was in the churchyard at Limpsfield, Sussex. Jelka, who died a few days later, was buried next to him. A self-proclaimed atheist and disciple of Nietzsche to the end, one who spent almost his whole life as an expatriate and who questioned his very identity as a genuine ‘British composer’, his final resting place summed up the conundrums and contradictions that were the complex yet ever-compelling personality of Frederick Delius.

This article originally appeared in the February 2012 issue of Gramophone.