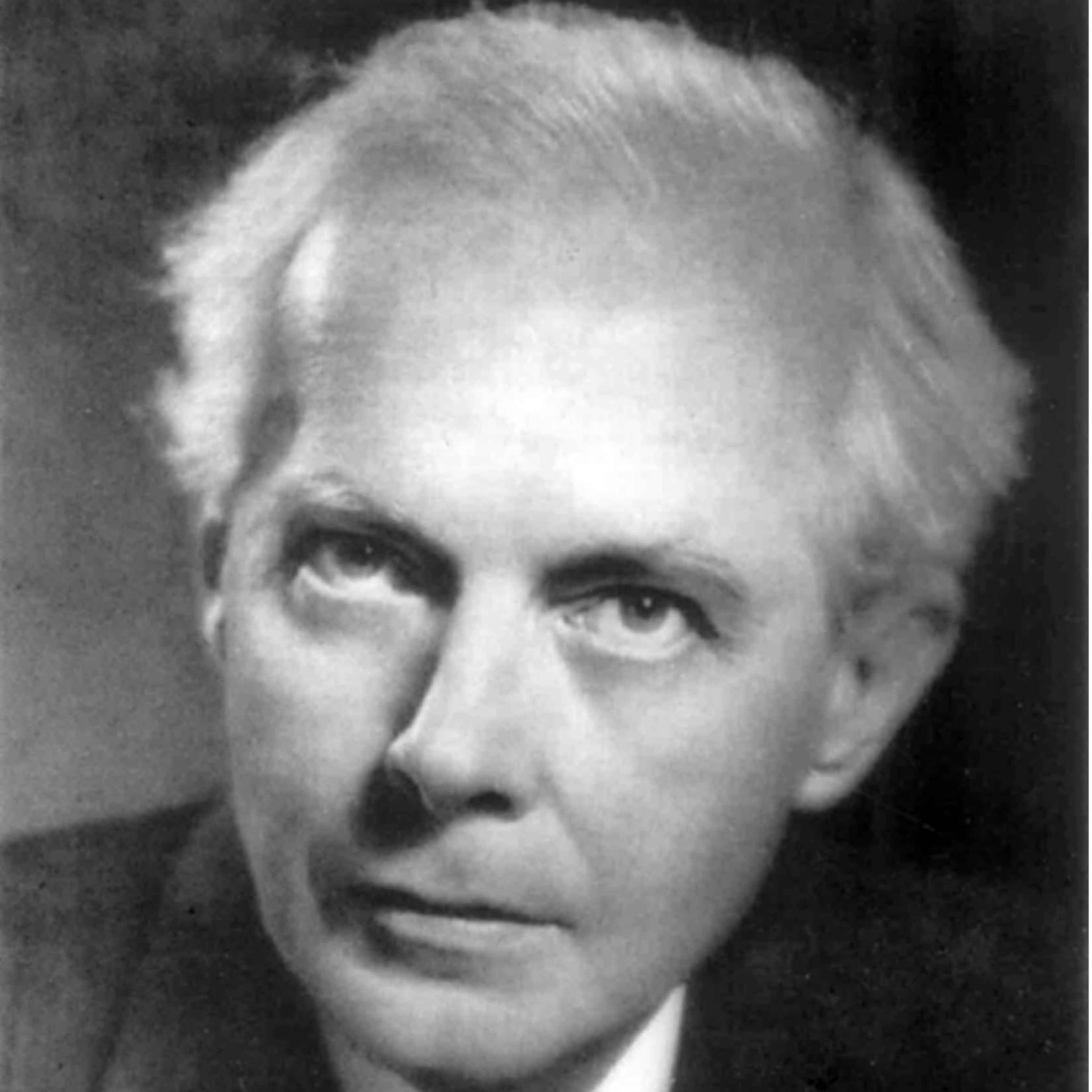

Bartók

Born: 1881

Died: 1945

Béla Bartók

One of the 20th century’s most important and individual composers, cherished for his intellectual rigour, uncompromising individuality and personal sound world.

Explore Bartók's life and music...

Top 20 Bartók Recordings

From the Concerto For Orchestra to Bluebeard's Castle, here are Béla Bartók's greatest works in outstanding recordings from Pierre Boulez, Susanna Mälkki, Gidon Kremer, Martha Argerich and more... Read more

Béla Bartók – the life and music of the Hungarian maverick

Béla Bartók’s music takes listeners on a journey through folklore and fantasy. Rob Cowan offers a guide to exploring his compelling genius... Read more

Inside Bartók's Solo Violin Sonata

Rob Cowan talks to violinist James Ehnes about the demands of Bartók’s Solo Violin Sonata... Read more

Bartók’s piano concertos – the pianist’s sternest test

Tackling Bartók’s three piano concertos is tantamount to conquering Mount Everest – but is the view from the summit worth the climb, asks Geoffrey Norris... Read more

Bartók’s early years – like his final ones – were spent in economic hardship and poor health. His father, a director of the local agricultural college, was a good amateur pianist; his mother taught piano after her husband’s death (when Béla was seven), trekking round from school to school with her young son and daughter, eking out a living. Bartók suffered from bronchitis and pneumonia and was treated (mistakenly) for curvature of the spine.

He was shy and highly introverted, a small, retiring man who remained physically frail all his life. To make up for it, he had a cast-iron will that brushed aside rejection, incomprehension and failure. He began composing aged nine and at 10 gave his first concert as ‘pianist-composer’. In 1894 the family moved to Pressburg (Bratislava) where Bartók studied piano before enrolling at the Academy of Music in Budapest.

In 1904, the year after graduating, he made a discovery that changed his life. Up till then his musical heroes had been Richard Strauss, Liszt and his slightly older fellow countryman Dohnányi. But listening to Hungarian folk music galvanised his creative thinking. With his friend Zoltán Kodály, Bartók went on lengthy trips armed with an Edison recording machine and a box of wax cylinders to collect systematically the folk tunes as performed by the peasants of Hungary, Transylvania, Carpathia and even as far afield as North Africa (1913) and Turkey (1936). Their work, catalogued and documented, was hailed as a major piece of ethnomusicology.

Thereafter, this music fed his soul and all his subsequent music is imbued with the varied character of his native folk music. The Budapest Academy offered him a teaching post in 1907 (piano, not composition, which Bartók always refused to teach) and he stayed there until 1934. The more he composed, the more his music became austere and experimental and, though it aroused strong opposition in his own country, outside Hungary his reputation grew steadily from a limited number of performances. Parallel to this was his burgeoning career as a pianist, predominantly in his own works.

Bartók saw that after the Anschluss in March 1938, it would be only a matter of time before Hungary fell to the Nazis. He was 58 years old, supporting his mother, wife and family – what was he to do? His mother’s death in 1939 decided him. He would go to the United States. He was given a position at Columbia University and he composed and played a few concerts but the American public was indifferent. Though not totally impoverished at this time as legend has it, he certainly had very little money and his health went rapidly downhill when leukaemia was diagnosed.

Isolated, somewhat embittered at the lack of recognition and, worst of all, in increasing pain, Bartók’s final completed score turned out to be his most popular, the Concerto for Orchestra. Before he died (of polycythemia), leaving a handful of works unfinished, he lamented: ‘The trouble is that I have to go with so much still to say.’

Béla Bartók – the sounds of his two names are the sounds of the two sides of his music, one soft and romantic, the other hard and angular. Without doubt, he’s one of the 20th century’s most important and individual composers, though his influence on other composers is far more limited than is sometimes claimed. Some of his work is easily accessible (Concerto for Orchestra and the Third Piano Concerto, for instance); more often than not it makes tremendous demands on the listener. Musicians sing his praises for his intellectual rigour, for his totally uncompromising individuality and the personal sound world he dreamt up. They also like to rise to the particular technical demands Bartók makes on them. Connoisseurs of the genre are of the opinion that his six string quartets are the greatest original contribution to the medium since Beethoven.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.