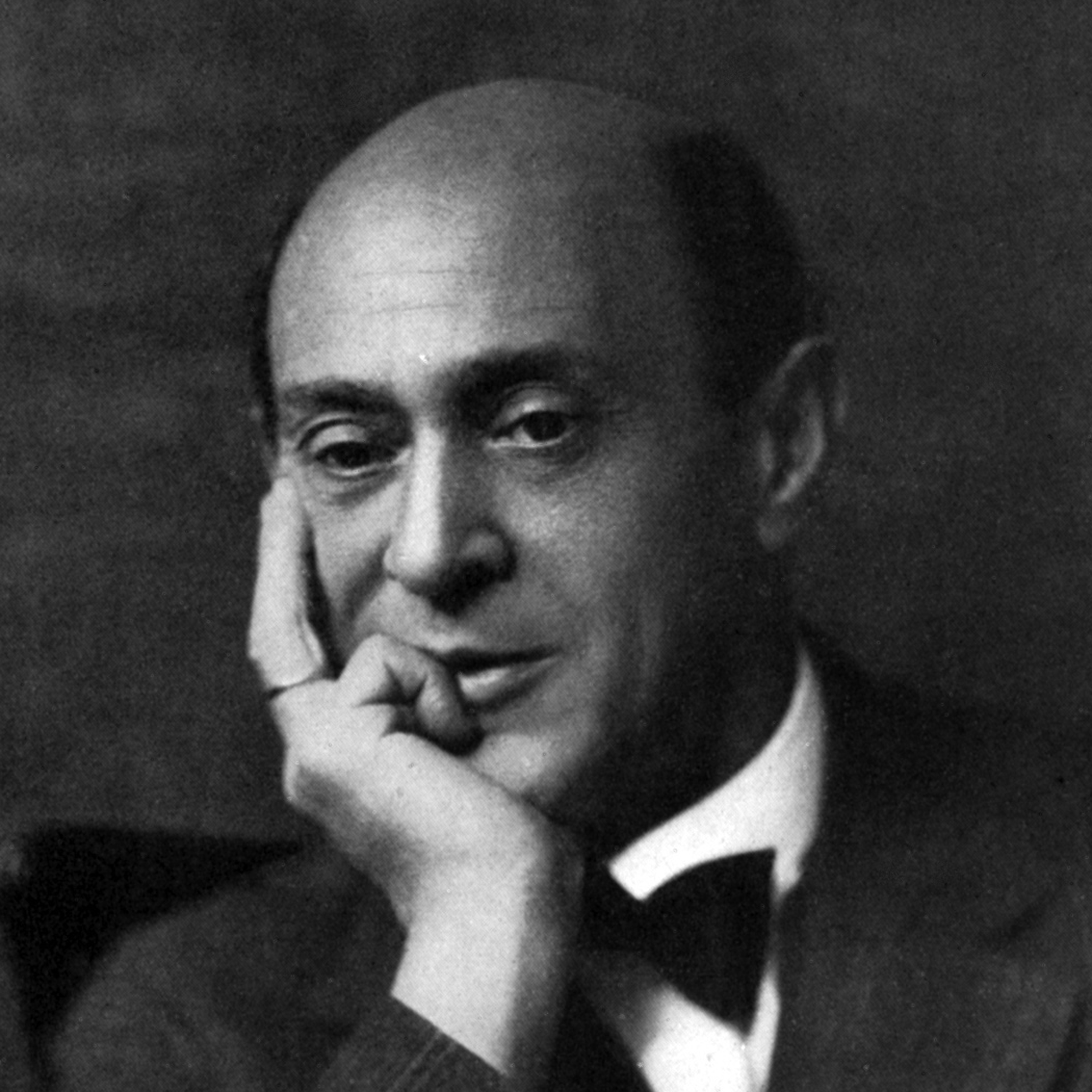

Schoenberg

Born: 1874

Died: 1951

Arnold Schoenberg

Schoenberg may fairly be said to have been one of the most influential musicians in history with his advocacy of the 12-note technique.

Explore Schoenberg's life and music...

Inside Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht

Hannah Nepil talks to members of the Belcea Quartet about Schoenberg’s masterpiece... Read more

The events in the life of this brave giant can be briefly sketched; his music and his ideas need a book to themselves. His father Samuel, who ran a shoe shop and sang in local choral societies, died when Schoenberg was 16, forcing him to take a job in a bank to support his mother and sister. For the man who was to become the most revered musical theoretician of the age and a great teacher, Schoenberg had remarkably little formal training, mainly gained from counterpoint lessons with Alexander Zemlinsky, who became his brother-in-law in 1901.

To those who think of Schoenberg as a purveyor of ‘squeaky-gate’ music, it comes as a surprise to hear his first two undoubted masterpieces, Verklärte Nacht (‘Transfigured Night’, 1899) and the mammoth Gurrelieder (1911), for they are lusciously scored, richly Romantic works in the traditions of Brahms and Wagner. From the early 1900s onwards he became increasingly adventurous and his compositions provoked a furore whenever they were played. Why? Schoenberg was frustrated by what he saw as the limitations of current musical language. What Wagner and others had been hinting at, he now openly embraced: music that, for the first time, had no key – atonal music. The sounds that emerged were greeted with incomprehension; it seemed to those listening as though they were being subjected to an assault of cacophonous, random, improvised notes. This wasn’t music as they understood it – and indeed Schoenberg was writing in a new language, so how could they understand? This was meaningless gibberish.

After a spell in Berlin where he conducted a kind of intellectual cabaret called Überbrettl, he moved back to Vienna, devoting himself to composition and teaching, gradually assimilating a reputation as a formidable musical thinker and attracting a group of devoted disciples who shared his experimental aims, among them Alban Berg and Anton von Webern, a group that musical history now refers to as the Second Viennese School (as opposed to the school of Haydn and Mozart). Critical hostility to his music in Vienna extended to antisemitic smears and violent abuse. But Schoenberg pugnaciously held his ground.

During the First World War he served sporadically in the Austrian Army. Once the conflict had ceased, discouraged by the lack of performances of his work, he formed the Society for Private Performances. Here his music and that of his followers could be heard in ideal conditions – critics were not invited. In 1922, about the time the Society was disbanded, he began work on the Suite for Piano, Op 25, the first formal 12-tone piece to be composed.

Three years later he was made a professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin. The rise of the Nazis ensured that he was dismissed from his post. Although born a Jew, he had converted to the Christian faith in 1898; moving to Paris in 1933, confronted with the German persecution of Jews, he reconverted to Judaism and left Europe for America.

The first year he spent in Boston but in 1935 he was made a professor at the University of Southern California, moving on to UCLA in 1936. Here he taught until 1944 when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 70. In April 1941 he became an American citizen; he died in Los Angeles.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.