Elgar

Born: 1857

Died: 1934

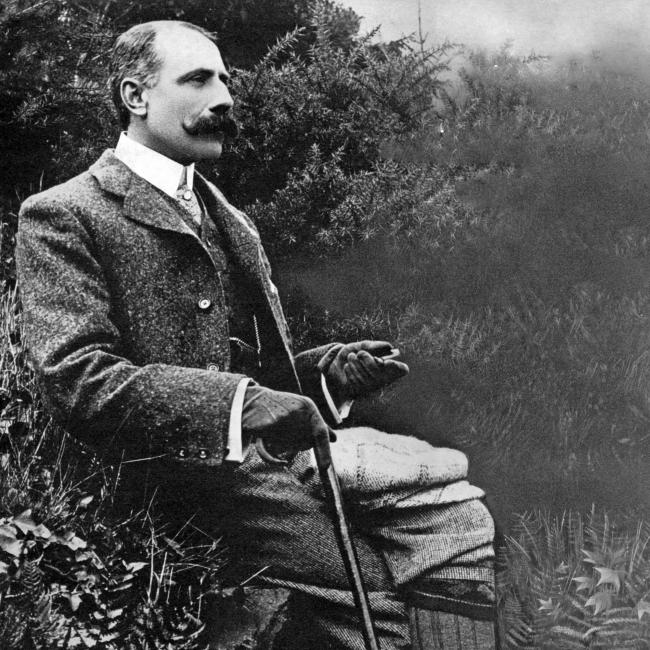

Edward Elgar

Elgar worked firmly within conventional 19th century German harmonic and structural traditions, yet his voice is quintessentially English. His lyrical side conjures up tranquil pastoral beauty; his pomposity and ebullience remind us of the British bulldog – one with teeth.

Explore Elgar's life and music...

Top 10 Elgar recordings

Ten of the finest recordings of Elgar's music, selected by Gramophone... read more

Why Edward Elgar was more than just an English gentleman

The idea that Edward Elgar wrote restrained, old-fashioned music can still persist abroad, but many international musicians are discovering that his music that is well worth championing, writes Andrew Farach-Colton... read more

Elgar Remembered

A centenary tribute by Compton Mackenzie (Gramophone, June 1957)... read more

Elgar: A Biography

Elgar’s father was at the centre of Worcester’s musical life, on friendly terms with the local gentry and clergy connected with the Anglican Cathedral. By the age of 12 his son was deputising for him at the organ and had taught himself (under his father’s guidance) the violin so that he could join in the music-making of local ensembles. He also won a reputation for his improvising abilities on the piano. Having left school at 15 and spent an unsuccessful year in a lawyer’s office, he determined on some sort of career in music. This took the form of giving piano and violin lessons locally and, in 1879, being made bandmaster at the County Lunatic Asylum.

During his five years’ involvement there, he wrote and arranged dozens of works for the motley ensemble to play at dances, entertainments and so forth – a formative experience, for he could experiment with every kind of instrumental combination at will. Simultaneously he played in an orchestra in Birmingham and conducted another amateur group in Worcester. By the time of his marriage in 1889, Elgar was thoroughly versed in the ways of composing – he would become an orchestrator of unsurpassed brilliance – and his new wife, Caroline Alice Roberts, introduced him into moneyed society. It also gave his creative impetus and his musical ambitions the boost they needed. All of Elgar’s important music was written during the 30 years of his marriage to Alice. They had one child, their daughter Carice, who was born in 1890 and died as recently as 1970.

The next 13 years saw the transformation of Elgar from a provincial small-time musician to a great composer of international standing, culminating in a knighthood in 1904. Orchestral and choral works were his main preoccupations. The demand for new choral works was insatiable and Elgar’s lifelong connection with choirs and his immersion in the Catholic faith stood him in good stead – the success of his religious and secular cantatas The Black Knight, The Light of Life, King Olaf and Caractacus paving the way for his 1900 masterpiece The Dream of Gerontius. By then, Elgar’s name was widely known as a composer of individuality and depth, especially after the appearance in 1899 of another masterpiece, perhaps his most loved work, the orchestral portaits of his friends featured in the Enigma Variations.

Now living in London, his religious faith receding, Elgar turned his attention to what he considered to be the pinnacle of the composer’s art – the writing of a symphony. He achieved his ambition in no small measure, producing two masterworks, the first in 1908, the second in 1911. A third large-scale work, the inspired Violin Concerto, was premiered in 1910 by Fritz Kreisler.

Elgar was awarded the highest British honour for artists, the Order of Merit, in 1911; the next year saw the completion of his final large-scale choral work, The Music Makers, in which, in a weirdly prophetic vision, Elgar used thematic ideas from his past work, uniting them in one single conception. How could he have known what was to occur, for after his symphonic study Falstaff (1913) he wrote nothing more of importance until 1919; there’s a final magnificent autumnal flourish with his Cello Concerto, String Quartet and Piano Quintet and then…nothing. After his wife’s death in 1920, Elgar lost the urge to create (he tried hard, though unsuccessfully, to complete a Third Symphony). He was made Master of the King’s Music in 1924 and given a baronetcy in 1931, but for the last 14 years of his life, returned to his roots in Worcester, he was all but silent as a composer.

Elgar Podcasts

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.