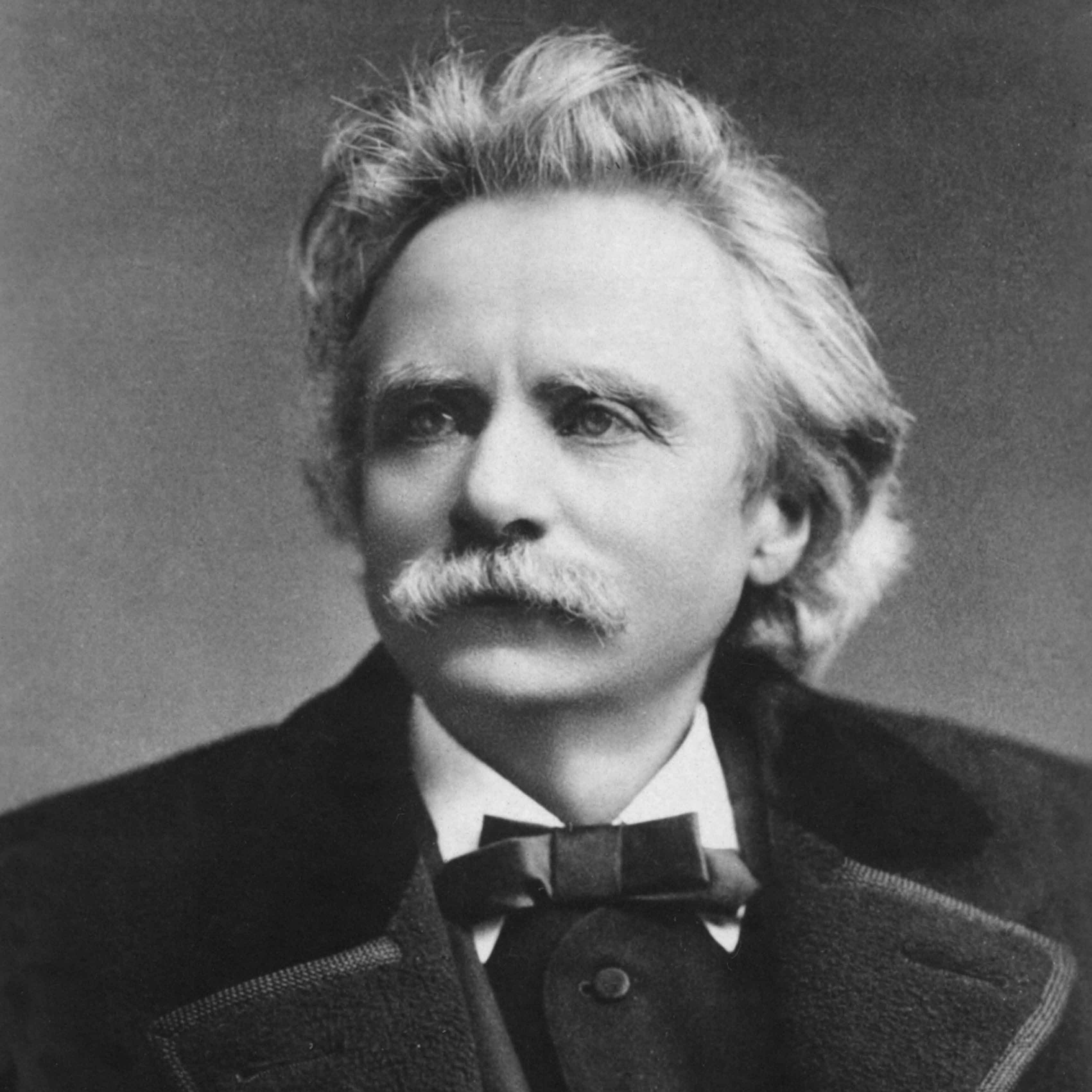

Grieg

Born: 1843

Died: 1907

Edvard Grieg

Grieg’s music is Norway in just the same way that Elgar and Vaughan Williams are England. It is full of the idioms of Norwegian folk music synthesised with the German Romantic tradition. Like Chopin, Grieg was more comfortable in miniatures than large forms (his early symphony was not a success), used the piano for the vast bulk of his musical expression and fed off a proud nationalism.

Explore Grieg's life and music...

Top 10 Grieg recordings

Gramophone's guide to the essential recordings of Edvard Grieg's music – from Dinu Lipatti to Anne Sofie von Otter... Read more

Masterclass: Grieg's Piano Concerto

Pianists Stephen Kovacevich and Jean-Yves Thibaudet give their perspectives on Grieg's youthful masterpiece, and Richard Whitehouse provides a detailed analysis... Read more

Grieg remembered

Reidar Storaas surveys the life and works of Edvard Grieg (Gramophone, June 1993)... Read more

Grieg’s great-grandfather was a Scot who emigrated to Bergen after the Battle of Culloden, changed his name from Greig and became British Consul there, a post subsequently held by his son and grandson. The music came from Edvard’s mother, a talented amateur pianist, but it was largely due to the persuasion of Norwegian violinist Ole Bull, who heard the young Grieg play the piano, that a musical career came about. The parents were reluctant and Grieg, who’d had thoughts of becoming a priest, hated the Leipzig Conservatory where he was sent.

However, he had the opportunity of hearing Clara Schumann play her late husband’s Piano Concerto and Wagner conduct Tannhäuser; the young Arthur Sullivan was a fellow student. Here, too, he developed pleurisy which left his left lung seriously impaired, bequeathing him precarious health and diminished energy for the rest of his life.

He returned not to Oslo but to Copenhagen in 1863; there the revered Niels Gade, founding father of the new Scandinavian school of composition and Denmark’s leading composer, befriended Grieg, inspiring him to form the Euterpe Society, dedicated to promoting Scandinavian music. This he did with the aid of another gifted young composer, Rikard Nordraak. ‘From Nordraak,’ wrote Grieg, ‘I learnt for the first time to know the nature of Norwegian folk tunes and my own nature.’ Alas, Nordraak died in 1866 at the age of 24 (though not before he’d written what is today’s Norwegian national anthem).

In 1867 Grieg married his cousin, the talented singer Nina Hagerup, who would become the chief interpreter of his songs, but a period of despair ensued: he had found the key to his own musical voice yet his missionary zeal in promoting Norwegian composers and its music met with opposition; then his first and only child, a 13-month-old girl, died in 1869. It was a letter from Franz Liszt not only praising his music but inviting him to Rome that did more to encourage him than anything. After the meeting with Liszt in 1869, he returned to Norway and opened a Norwegian Academy of Music.

In 1869 he gave the first performance of his Piano Concerto, the work by which most people know him. This, with the first set of Lyric Pieces (for piano) and two violin sonatas that had already been published, established him as one of the foremost composers of the time. Ibsen approached him to write the incidental music for the stage version of his Peer Gynt (a job which occupied Grieg for two years). In a short time, Grieg had become so famous that the government granted him an annuity to relieve him of financial burdens so that he could concentrate on composing. Ironically, apart from the Holberg Suite, all his most successful works were written by the time he was 33.

He visited England frequently and was showered with honours and decorations wherever he went, a much-loved figure. But Grieg was a shy, retiring, modest man, a republican not much impressed by medals and orders bestowed by royalty (though he confessed they were useful for putting on the top layer of his trunks when travelling: ‘The Customs officials are always so kind to me at the sight of them’). As he grew older, Grieg grew physically weaker and more reclusive, preferring the company of his wife and the tranquillity of his home at Troldhaugen, overlooking the Hardanger fjord near Bergen.

He died of a heart attack and, following a state funeral, his ashes were sealed in the side of a cliff round the fjord at Troldhaugen.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.