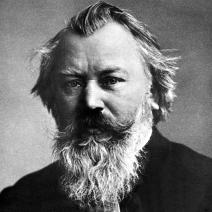

Brahms

Born: 1833

Died: 1897

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms (born May 7, 1833; died April 3, 1897) was one of the giants of classical music, he appeared to arrive fully armed, found a style in which he was comfortable – traditional structures and tonality in the German idiom – and stuck to it throughout his life. He was no innovator, preferring the logic of the symphony, sonata, fugue and variation forms.

Quick links

Guides to Brahms's music

Johannes Brahms: a biography

Johannes Brahms’s father was an impecunious double-bass player, eventually good enough for the Hamburg Philharmonic. At the age of six he was discovered to have perfect pitch and a natural talent for the piano. He made his first public appearance playing chamber music at the age of ten. A passing American impresario heard him and offered the wunderkind an American tour, but his teacher Otto Cossel forbade it before turning him over to Marxsen.

To supplement his income, the teenager played in taverns and, some say, bordellos. It remains a moot point whether this period left its psychological scars. His parents were an ill-matched couple and he frequently witnessed their violent arguments as a child; some have suggested he may have been impotent. Whatever the reason, Brahms never married and seems to have resorted to prostitutes when the need arose. In the 1880s, so the story goes, Brahms entered a somewhat dubious establishment and was accosted by a well-known prostitute with the greeting ‘Professor, play us some dance music,’ whereupon the great composer sat down at the piano and entertained the assembled company. Brahms sublimated his love and desire for women in his music. ‘At least,’ he said, recognising his awkwardness with women, ‘it has saved me from opera and marriage.’

Early works and influences

He began to compose, too, but when he met up with the Hungarian violinist Eduard Reményi, Brahms leapt at the chance of becoming his accompanist and off they went on tour. It proved to be a fortuitous move. In Hanover, he was introduced to Reményi’s old student friend the violinist Joseph Joachim, only 22 years old but already Konzertmaster to the King. Brahms and Joachim formed a firm friendship and Joachim, who was part of the Liszt circle, took Brahms with him to Weimar to meet the great man. Of more significance was Joachim’s introduction to Robert and Clara Schumann, then living in Düsseldorf. There’s a brief note in Schumann’s diary recording the event. It reads simply: ‘Brahms to see me (a genius).’ In his last article for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Robert Schumann wrote of Brahms as a young eagle and predicted great things from him. In fact, so enamoured did the Schumanns become of the young man that they invited him to move into their house. Schumann introduced Brahms to his publishers Breitkopf und Härtel who published his early works. When Schumann tried to commit suicide, Brahms was there at Clara’s side to help and comfort; he was there with her when Schumann died in 1856.

There’s no doubt that Brahms was in love with Clara but doubtful whether the relationship ever developed into anything more than a platonic friendship. They decided to go their separate ways after Robert’s death but Brahms’s correspondence with her reveals a deep spiritual and artistic affinity – it was probably the most profound human relationship Brahms ever experienced. Only a few years later, he was castigated by his friends for compromising a young singer named Agathe von Siebold. She inspired many songs and attracted him immensely but after becoming engaged to her wrote: ‘I love you. I must see you again. But I cannot wear fetters...’ Agathe naturally broke off the engagement.

The great works

Meanwhile, he had written his magnificent First Piano Concerto. It was hissed at its premiere in 1859 and the year later he had a further disappointment when he was turned down for the conductorship of the Hamburg Philharmonic.

See also: Top 10 piano concertos

Then an invitation to conduct in Vienna, his mother’s death in 1865 and father’s remarriage, loosened his ties with Hamburg. Eventually, in 1872, he decided to make the Austrian capital his base. His German Requiem and Alto Rhapsody from the late 1860s made him famous but it was the next two decades which saw the flowering of his genius.

He was offered the conductorship of the famed Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in 1872 but was so consumed with the need to compose that he resigned in 1875. Within three years he had completed his Symphonies Nos 1 and 2, the Violin Concerto besides the Academic Festival and Tragic overtures. From the rigours of conducting and playing his music all over Europe, Brahms escaped every summer to the country, either to stay in Baden-Baden where Clara Schumann had a house or to Ischl where Johann Strauss II had a villa (the two men were good friends).

Autumnal romanticism

In 1878 he was taken to Italy by a surgeon friend, the first of many visits to a country he came to love. Masterpiece followed masterpiece in the 1880s: the B flat Piano Concerto, the Third and Fourth symphonies and the Concerto for violin and cello.

See also: Top 10 symphony composers

In the 1890s, he abandoned larger forms and concentrated on chamber music and more intimate, personal piano works, all tinged with nostalgia and a warm, steady glow of autumnal romanticism. Perhaps they reflected a growing realisation of life’s transience: it seemed as though all those who mattered to him were dying and when Clara Schumann too died in 1896, it affected him deeply. His appearance deteriorated, his energy disappeared and he was persuaded to see a doctor. Only months after Clara’s death, he too had gone, like his father, from cancer of the liver.

Brahms's legacy

Brahms had much in common with Beethoven. Short in stature, unable or unwilling to have lasting relationships with women, bad tempered and lovers of the countryside, they even walked about Vienna in the same way with head forward and hands clasped behind the back. Like Beethoven, Brahms had an unhappy childhood and was a prickly, uncompromising man. He nevertheless had a wonderfully generous side to him when the mood took him – his help and encouragement to young composers like Dvořák and Grieg who needed a leg up. He was a sociable man who attracted many friends but he could be quite remarkably tactless on occasion, blunt to the point of gruffness, grumpy and cruelly sarcastic in later life, characteristics that didn’t make his relations with other people any easier. After one party in Vienna, it’s said Brahms left saying, ‘If there’s anybody here I haven’t insulted, I apologise.’

Younger members of the New German School, the Liszt- and Wagnerites, sneered at his rock-like loyalty to Classical thought and design. Some, like Hugo Wolf, a Wagner follower, bitterly attacked Brahms. Tchaikovsky had no time for him at all. ‘I have played over the music of that scoundrel Brahms,’ he confided in his diary. ‘What a giftless bastard!’ One element is lacking in his music and that is wit. ‘When Brahms is in extra good spirits,’ quipped his friend the violinist Hellmesberger, ‘he sings “The grave is my joy”.’ It’s all serious stuff, there’s no superficial prettiness and few hints at empty virtuosity in his keyboard writing – it’s all logically worked out by a meticulous, perfectionist craftsman. Some find him a turgid Teutonic. Certainly a lot of his music, especially his early work, can sound thick textured and plodding. But Brahms’s many masterpieces have a confidence and ebullience, an irresistible lyricism and melodic charm that have no sign of losing their appeal and rich rewards long after his death.

The Gramophone Podcast: Brahms episodes

Stephen Hough on Brahms's late piano music

Edward Gardner on Mendelssohn and Brahms

Jack Liebeck on the Brahms and Schoenberg violin concertos

Anne-Sophie Mutter and Pablo Ferrández on Brahms's Double Concerto

Key recording

The Symphonies

Gewandhausorchester / Riccardo Chailly (Decca)

'Chailly belongs to that select group of conductors on record who direct all four Brahms symphonies almost equally well. Such conductors – Weingartner, Klemperer, Boult, Wand and Loughran in his fine Hallé cycle – tend to belong to the spare-sounding, classically orientated school of Brahms interpretation, a school to which Chailly himself also subscribes.'

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.