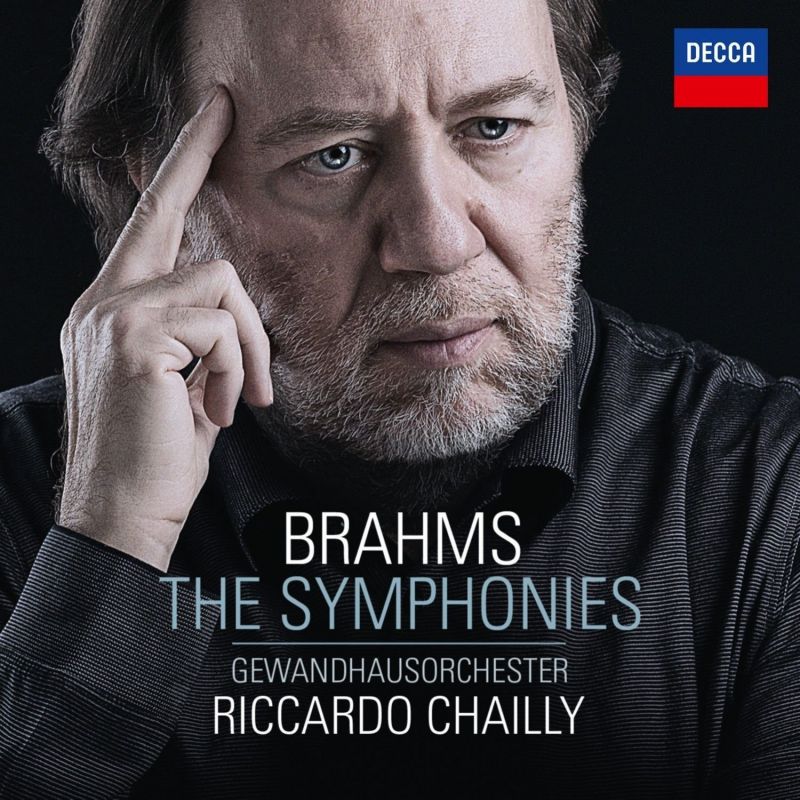

BRAHMS The Symphonies

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Johannes Brahms

Genre:

Orchestral

Label: Decca

Magazine Review Date: 10/2013

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 334

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 478 5344DH3

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Symphony No. 1 |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra Riccardo Chailly, Conductor |

| Symphony No. 2 |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra Riccardo Chailly, Conductor |

| Symphony No. 3 |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra Riccardo Chailly, Conductor |

| Symphony No. 4 |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra Riccardo Chailly, Conductor |

| Variations on a Theme by Haydn, 'St Antoni Chorale |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer |

| Tragic Overture |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer |

| Academic Festival Overture |

Johannes Brahms, Composer

Johannes Brahms, Composer |

Author: Richard Osborne

Leipzig was never especially kind to Brahms. His First Piano Concerto was jeered off the stage there in 1859. Fences were mended in later years – it was in Leipzig that Brahms conducted his own Second Symphony for the first time – but it is a curious fact that during the last century the Gewandhaus Orchestra made virtually no Brahms symphony recordings of distinction. Even Kurt Masur’s late-1970s Philips cycle was a flop.

Riccardo Chailly has changed all that. During his eight-year reign in Leipzig, the Gewandhaus Orchestra has become as articulate a Brahms ensemble as any in Austro-Germany. It helps, of course, that Chailly himself is a trusted Brahmsian. As Alan Sanders noted in these columns at the time of the launch of Chailly’s Royal Concertgebouw cycle in November 1988, his Brahms is ‘strong, serious, unidiosyncratic and very directly expressed’.

Chailly belongs to that select group of conductors on record who direct all four Brahms symphonies almost equally well. Such conductors – Weingartner, Klemperer, Boult, Wand and Loughran in his fine Hallé cycle – tend to belong to the spare-sounding, classically orientated school of Brahms interpretation, a school to which Chailly himself also subscribes.

This is less richly coloured Brahms than you will hear in Berlin or Vienna, though the sound palette is by no means limited. The Leipzig string-playing can be wintry or warm. Yet when violas and cellos ravish the ear in the Fourth Symphony’s slow movement, the ravishment is never bought at the expense of a trademark clarity of texture that renders audible each instrumental line, right down to the contrabassoon’s quietest note. The clean, open sound of the orchestra’s superb winds also helps aerate textures. The first oboe is outstanding, as are the horns, which happily have not entirely lost their eastern European accent.

In Vienna in the 1880s Brahms symphonies were ‘new music’, known for the relative astringency of their sound. These Leipzig performances give us a hint of that astringency. Recorded with a fair degree of immediacy in a clean but lively acoustic, it is music-making that provokes more than it soothes. Listeners like the schoolboy in the Punch cartoon, who thought the claret might be improved by the addition of a teaspoon of sugar, should be on their guard.

Back in 1988, Chailly’s Brahms was seen as being not especially Italianate. If it wasn’t then, it is more so now. His account of the Haydn Variations resembles Toscanini’s in the tautness of its argument and its finely adjusted sense of tempo relations within and between variations. In the symphonies, however, the analogy works less well. Where Toscanini in his later years would often harry the music, bending it too much to his will, Chailly’s approach is more nearly aligned to Klemperer’s, where swift tempi, buoyant phrasing and forward winds are married to strongly drawn lines which move the music unerringly towards its appointed goal.

It is an approach that informs the entire cycle. Weingartner spoke of the First Symphony ‘taking hold like the claw of a lion’, which indeed it does in Chailly’s performance. But, like Klemperer, Chailly brings a similar approach to the first movement of the Second Symphony. The result is a degree of urgency which more pastorally minded Brahmsians might think better suited to the tragic pronouncements of the Fourth Symphony than the ‘lion and the lamb’ mood of the Second. Yet everything is of a piece. Rarely have I heard so angst-ridden a realisation of the moment towards the end of the first movement where a woodland horn effects an extraordinary dissolution of the germinal D-C sharp-D motif with which the symphony begins. There will be no such controversy about the symphony’s two closing movements. It’s difficult to imagine them being better done. As to the Fourth Symphony, Chailly’s new account has a concentration of gesture and urgency of movement which his earlier Concertgebouw reading rather lacked. The opening still sounds understated but the performance builds steadily until the coda glows white hot.

Wilhelm Furtwängler liked to argue that it is in moments of transition that the deeper truths lie. This may be so but it requires Brahms-conducting more like that which we encounter in Kurt Sanderling’s epic 1971-72 Dresden cycle to realise the point. Broad tempi and sudden indwellings are not Chailly’s way. Yet his account of the Third Symphony – as finely ordered and dramatically direct a performance as any on record – misses few if any of the work’s darker undercurrents. The nocturnal mysteries of the two inner movements are beautifully realised.

Most Brahms symphony cycles occupy three discs. This one occupies two, with a third disc given over to an intriguingly prepared anthology of Brahms orchestral pieces of varying degrees of familiarity. It begins with the Tragic Overture. It’s here that you can acquire in summary form a sense of the quality of timing and attack in these Leipzig performances, of the players’ scrupulous observation of dynamics and Chailly’s practised way with those almost imperceptible changes of rhythmic motion which lead us through the work’s haunted dream states. After that, we drop into an unexpected pool of quiet for the first of two orchestral transcriptions of late Brahms piano pieces. The Haydn Variations follow and, after them, a pleasing rarity: the nine-movement suite for small orchestra which Brahms derived from his Liebeslieder Waltzes at the request of conductor Ernst Rudorff. Here, more than in the three Hungarian Dances with which the disc ends, we have a shrewd sense of the Gewandhaus players giving their rivals in Vienna and Budapest a decent run for their money.

Towards the close of the anthology we have the Andante of the First Symphony as it was originally heard in Karlsruhe, Munich and Cambridge in 1876-77. Brahms was a great destroyer of drafts, so this is a rare example of a significant staging-post which survives in the public domain. The Cambridge performance was not conducted by Brahms. He had been reluctant to cross the North Sea to receive in person the honorary degree which Cambridge had proposed and which it now churlishly withdrew.

Not the least of the unexpected delights of this new set is the juxtaposition of this Andante, which Cambridge folk heard in 1877, with the rip-roaring performance by Chailly and his Leipzig players of the Academic Festival Overture which Brahms wrote for Breslau University some four years later. A chance juxtaposition or a well-aimed raspberry? The latter, I’d like to think.

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.