Tchaikovsky

Born: 1840

Died: 1893

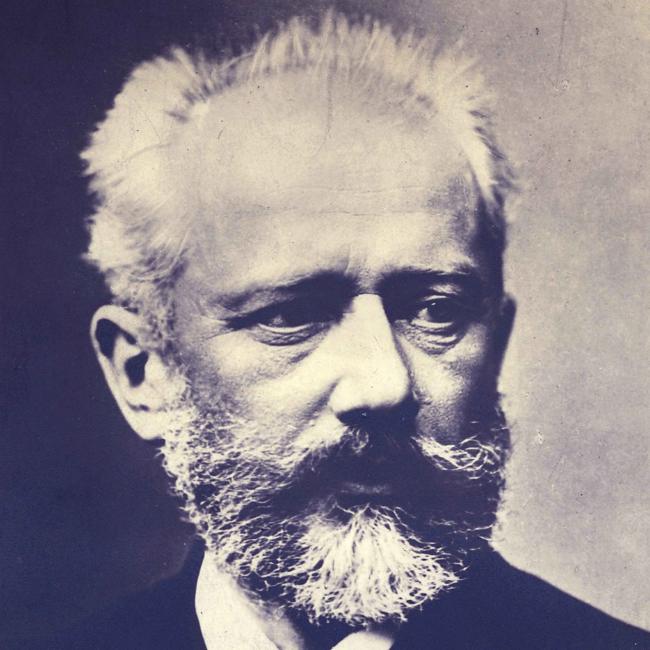

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (born May 7, 1840; died November 6, 1893) is the most popular of all Russian composers, his music combining some nationalist elements with a more cosmopolitan view, but it is music that could only have been written by a Russian. In every genre he shows himself to be one of the greatest melodic fountains who ever lived.

Quick Links

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: a biography

Tchaikovsky's father was a successful mining engineer while his mother was the artistic, sensitive one, French by birth, and a good linguist. Pyotr was the second of her six children. He had a good education, a French governess and a stable beginning to his life. As early as eight, though, signs of neurosis manifested themselves, often brought on by listening to music.

In 1848 his father resigned his government post, hoping for a better position in Moscow. This did not materialise and Pyotr and his elder brother were packed off to boarding school. This second period of relative security ended in 1854, when his mother died of cholera. His relationship with her was profound to the point of obsession and it can be argued that he never recovered from this blow.

See also: Top 10 Romantic composers

Giving up the day job

His period at the St Petersburg School of Jurisprudence led to a job as a clerk in the Ministry of Justice, a job for which he was singularly unsuited. The decisive factor was the founding of what would become the St Petersburg Conservatory in 1862 by Anton Rubinstein. Tchaikovsky followed his teacher Nicholas Zaremba to the Conservatory and the following year resigned his post to become a full-time musician. Only two years later, Rubinstein’s brother Nikolai invited Tchaikovsky to teach harmony at the Moscow Conservatory.

The first large-scale works

For a time, he lived in Nikolai Rubinstein’s house in Moscow while his first large-scale compositions began to emerge (Symphony No 1,Winter Daydreams, among them). His nervous disorder began to manifest itself again in the forms of colitis, hypochondria, hallucinations and numbness in his hands and feet.

See also: Top 10 symphony composers

In 1868 a Belgian soprano, Désirée Artôt, part of an opera company visiting St Petersburg, became attached to Tchaikovsky and for a while he contemplated marriage. She, however, was as celebrated for her sexual peccadilloes as for her singing and soon after married a Spanish singer. Tchaikovsky accepted it all philosophically (on the surface at least). The music that followed the affair was the first version of his famous Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture, one of his most popular works, containing the most radiant love music he ever wrote.

Failure and rejection

Tchaikovsky’s career progressed in an untroubled way for the next few years. He contributed music criticism to Moscow newspapers, made many trips abroad, taught and continued composing. Then came a series of crises. Late in 1874 he finished his Piano Concerto No 1 and played it through to Nikolai Rubinstein, to whom he had dedicated it. Rubinstein denounced it as ugly and unplayable. Tchaikovsky was stunned. Rubinstein eventually relented and became a fervent champion of the concerto but Tchaikovsky was flung into a morbid depression by Rubinstein’s reaction to the work and the initial failure of his ballet Swan Lake. He tired of his work at the Conservatory, he had financial problems and, above all, nagging away at the back of his mind, was the guilt attached to his homosexuality.

A guardian angel

At exactly the right time, a guardian angel appeared in his life. Through the violinist Kotek, an affluent and cultured widow, Nadezhda von Meck, heard about Tchaikovsky and engaged him to write some music for large fees. She was a remarkable woman aged 45, the mother of 11 children and passionately fond of music.

But shortly after his introduction to Mme von Meck, another crisis hit Tchaikovsky. A pretty blonde, a 28-year-old music student named Antonina Milyukova, became obsessed with him. Without disclosing to Antonina his true sexual preference, without loving her, thinking that marriage would scotch the current rumours of his ‘deviancy’, Tchaikovsky nevertheless married her in July 1877. It was a disaster. He was ‘ready to scream’ (he admitted) the first time they were alone together. Five days later, he was going out of his mind and fled to his sister’s estate at Kamenka. Later he attempted to kill himself by standing in the freezing Moscow River. He next went to St Petersburg, where his brother Anatol, a lawyer, made suitable arrangements for a separation. The couple were never divorced and never met again.

Financial security

Nadezhda von Meck was kept informed of this relationship by Tchaikovsky (though never of the real cause of its failure) and the same year (1877) settled an annual allowance of 6000 roubles on him. His Fourth Symphony (dedicated to Mme von Meck), the opera Eugene Onegin and the great Violin Concerto were but three of the works written shortly after Tchaikovsky had been given financial security.

For the next 13 years, this extraordinary relationship continued, one of the most curious and moving in musical history. It was the perfect relationship for the composer, a replacement for his lost mother, a woman who had no personal or sexual interest in him, yet who supported him financially and emotionally. In all the period of their touching friendship they never met. One of the conditions for her generous subsidy was that they should never become involved on a personal level.

The initial burst of unqualified masterpieces was followed by an uneven period (his opera Joan of Arc, the Second Piano Concerto, Capriccio italien and the Serenade for strings, the Piano Sonata and Piano Trio). By 1880 he was famous and respected. Then, between 1881 and 1888, he dried up.

Inspiration returned in 1888 with the Fifth Symphony. The government settled an annual pension on him and he made an extensive tour of Europe conducting his works to enormous acclaim. Then in 1890 came a letter from Nadezhda von Meck saying that, due to financial reversals, she was no longer able to subsidise Tchaikovsky. The composer replied expressing sympathy for her changed fortunes, pointed out that he was now financially self-sufficient and hoped their friendship would continue. The letter went unanswered. So did many more. Then he learnt that in fact Mme von Meck was not financially embarrassed and had used it merely as an excuse to discontinue the friendship. After 13 years, his trusted confidante and mother-figure had abruptly terminated their relationship. Perhaps she had discovered the truth about his homosexuality, perhaps she had become bored with Tchaikovsky’s letters; more likely, her family had put pressure on her to terminate the friendship and put an end to all the society gossip about its nature. It was a shattering blow to Tchaikovsky’s confidence and initiated a period of morbid depression.

In 1893 he completed his great Sixth Symphony, the Pathétique, and in June travelled to Cambridge to receive an Honorary Doctorate of Music. In October he conducted the premiere of the Pathétique (it was coolly received). On November 2, after an agreeable evening meal, he drank a glass of tap water. His friends were appalled. Didn’t he know it was the cholera season in St Petersburg, that no water should be drunk without first boiling it? Tchaikovsky, it seems, was unconcerned.

Death

There are many stories surrounding his death. The question of ‘Was it suicide or not?’ has fascinated scholars for over a century and provided the material for plays, novels, doctorates and romantic biographies. The most likely theory is the simplest one, that Tchaikovsky was a fatalist: someone who makes little effort in the face of threatened disaster and believes that all events are subject to fate. The fact is that Tchaikovsky died from cholera four days after drinking the water. One troubling piece of evidence confuses the cholera-suicide theories. Tchaikovsky’s body lay in state in his brother’s bedroom. It was then taken to Kazan Cathedral where mourners filed passed in their hundreds to pay their respects and touch the body. Not one of them contracted the highly contagious disease.

The Gramophone Podcast: Tchaikovsky episodes

Santtu-Matias Rouvali on Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake

Louise Alder: The Russian Connection

Arabella Steinbacher discusses Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.