Liszt

Born: 1811

Died: 1886

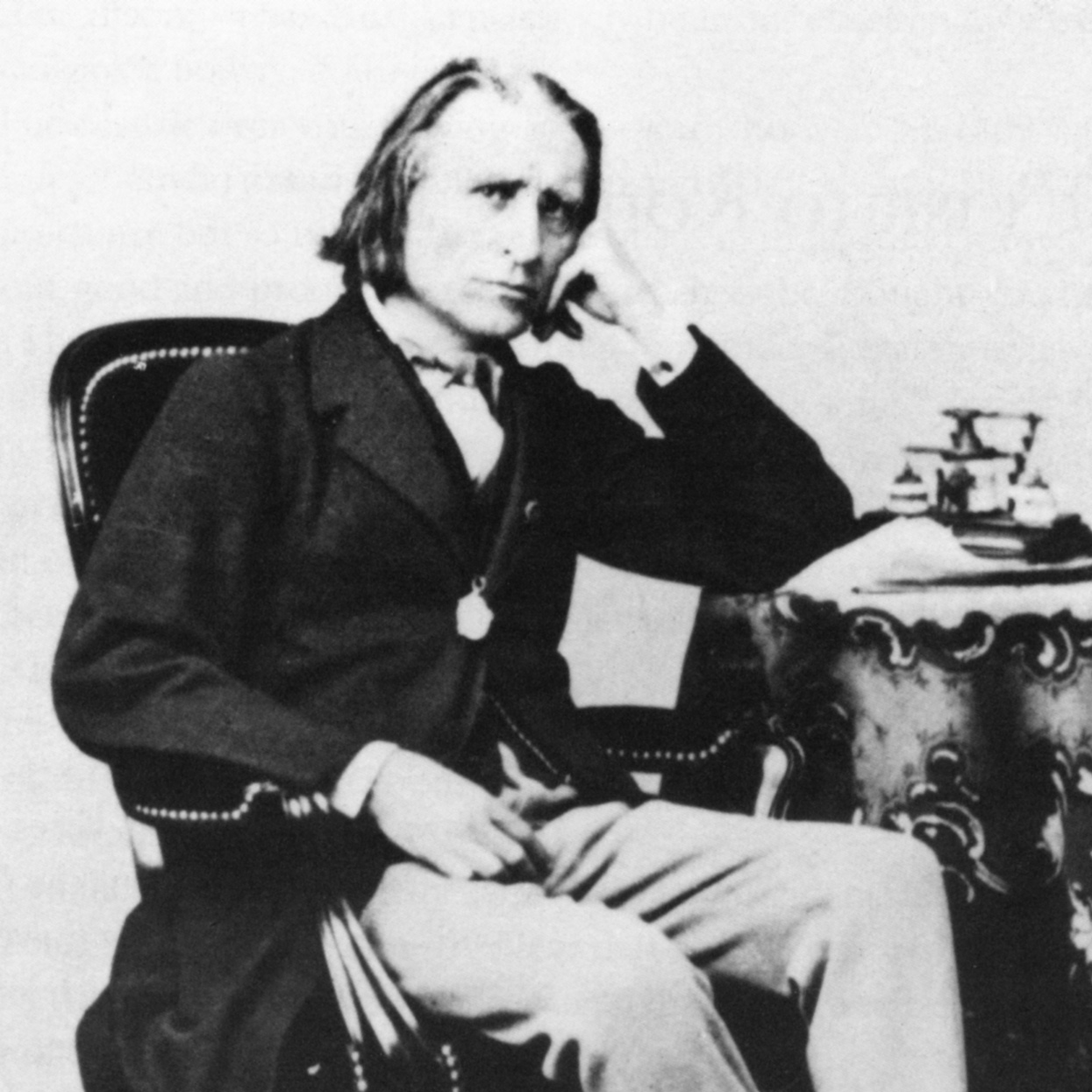

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt (born October 22, 1811; died July 31, 1886) was the very embodiment of the Romantic spirit. He worked in every field of music except ballet and opera and to each field he contributed a significant development.

Quick links

Franz Liszt: a biography

Composer, teacher, Abbé, Casanova, writer, sage, pioneer and champion of new music, philanthropist, philosopher and one of the greatest pianists in history, Liszt was the very embodiment of the Romantic spirit. Yet he remains the most contradictory personality of all the great composers. He was as arrogant and egocentric as he was also humble and generous; he was a profoundly spiritual man yet delighted in the pleasures of the flesh – at least 26 major love affairs and several illegitimate children (Ernest Newman said, ‘He collected princesses and countesses as other men collect rare butterflies, or Japanese prints, or first editions’); attracted to the life of a recluse, he loved luxury and the adulation of the public; he practised at the highest level of his art yet could demean himself with meretricious theatrics: all in all, a fascinating man.

Hungarian wunderkind

By nine Liszt could not only play the difficult B minor Concerto of Hummel in public but was able to extemporise on themes submitted by the audience. Prince Nicholas Esterházy was impressed enough to arrange for a group of Hungarian aristocrats to fund the musical education of the prodigy to the tune of 600 florins a year and Liszt, with his mother and ambitious father, moved to Vienna in 1821. His piano mentor there was the illustrious Carl Czerny, who refused to accept payment for the pleasure of teaching the Hungarian wunderkind. Liszt’s composition teacher was Salieri. Soon Liszt was giving concerts. At one, attended by Beethoven and in which Liszt played an arrangement of a Beethoven piano trio from memory, the great master is said to have kissed his brow and exclaimed, ‘Devil of a fellow! – such a young rascal!’ Liszt also made his bow as a composer at this time, one of those asked to contribute a variation on a theme by Diabelli.

Still only 12 and a finished pianist, Liszt left Vienna for Paris. A concert at the Opéra in March 1824 established him as one of the finest pianists ever heard. The fashionable salons welcomed him both in the French capital and in London. By the age of 16 Liszt was famous throughout Europe and financially self-sufficient.

Liszt’s father died suddenly of typhoid fever, enjoining his son to hand over his fortune to his mother in recognition of the person who had made it possible. Liszt, exhausted by constant touring, bowed out of the limelight for a few years, teaching, reading everything he could get his hands on and embarking on the first of his many passionate love affairs. Religion and philosophy for a time replaced music as the dominant force in Liszt’s life.

Chopin, Berlioz and Paganini

Then in 1830 he met three musicians who changed everything: Chopin, Berlioz (then virtually unknown) and Paganini. From Berlioz he learnt about the possible sonorities of the orchestra – Liszt’s later orchestral works testify to that; from Chopin he absorbed the poetry and refined, sensitive taste of the Pole’s piano style. But it was the electrifying effect of Paganini’s stage presence and the spectacular demands of his music that immediately fired Liszt’s imagination. Paganini had dramatically extended the possibilities of the instrument with his astounding technical prowess and Liszt consciously set out to emulate on the piano what Paganini had achieved on the violin. To achieve this involved creating a new pianistic technique.

For the next two years, Liszt shut himself away to master his objectives, daily practising assiduously to the point of exhaustion. His re-emergence on the concert platform was a major artistic event and the pianistic artillery he had acquired swept all rivals aside.

The height of his powers

In 1834 Liszt met the beautiful Comtesse Marie d’Agoult. The fact that she had a husband and three children was of no importance when it came to such a grand passion. Within a year, she had left her husband and joined Liszt in Geneva where Blandine, the first of their three children, was born. She died in 1867. Their second child was Cosima, born in 1837, destined to become the wife of Richard Wagner. Daniel, their third child, was born in 1839 in Rome but died at the age of only 20. For the next decade Liszt toured all over the continent, from Turkey and Russia to Portugal and Ireland, amassing a fortune along the way, heaped with honours, the intimate of royalty and statesmen wherever he appeared. Then in 1847, at the height of his powers, he changed direction.

The relationship with Marie d’Agoult had gradually disintegrated and, when they finally parted, Liszt took the children to live with his mother in Paris. Here his mistresses included Marie Duplessis (immortalised by Dumas as the Lady of the Camellias and by Verdi in his opera La traviata) and the dancer Lola Montez. While on a concert trip to Kiev in 1847 he met the Polish-born Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein, cigar-smoking, unhappily married, intellectual and who suffered from a morbid fear of fresh air. This was Liszt’s last great love. The two discovered a mutual interest in religion and mysticism, and within a short time the Princess had abandoned her husband and 30,000 serfs to join Liszt in Weimar, where he had been appointed Kapellmeister to the Grand Duke.

Liszt the music director

Here they lived as an unmarried couple for the next 10 years. Liszt’s duties were to direct performances of orchestral and operatic works. By the end of the decade, he had transformed Weimar into one of Europe’s greatest musical centres, the headquarters of the Music of the Future. Musicians flocked to Weimar. The works Liszt presented and conducted were of the widest variety, from premieres of new and experimental works to high-quality revivals of the classic repertoire. Liszt never allowed his personal preferences to dictate what he produced at Weimar. Even composers he personally disliked or whose music he did not care for had a hearing. He was also courageous enough to present a revival of Wagner’s Tannhäuser, a work by a political revolutionary sought by the authorities. He then followed it up with the world premiere of Lohengrin. He fought for funds to present other works by Wagner. The Duke’s refusal to fund the enterprise was one of the reasons for Liszt’s eventual departure.

Two other activities occupied Liszt during his reign at Weimar: teaching and composition. The amount he produced is simply staggering. What we hear today is only the tip of the iceberg. These years include 12 symphonic poems (a form he invented), the Faust and Dante symphonies, two piano concertos and the Totentanz for piano and orchestra, the great B minor Piano Sonata, literally hundreds of other pieces for the piano as well as revisions of all the piano music he had written in the 1830s and ’40s.

Although he resigned from his musical duties in 1859, Liszt remained in Weimar until 1861. The religious life again attracted him, however, and in 1865 Pope Pius IX conferred on him the dignity of Abbé. In 1879 he received the tonsure and the four minor orders but he was never ordained a priest. Yet he was allowed to discard the cassock and even marry if he so wished.

Liszt's lasting influence

From now on Liszt divided his time between his religious interests in Rome and teaching piano in Pest and Weimar (he was invited back in 1869). Liszt’s influence on the coming generation of music-makers is hard to exaggerate – the likes of Borodin, Balakirev, Rimsky-Korsakov, MacDowell, Smetana, Debussy, Saint-Saëns, Fauré, Grieg and even Brahms (for a time) all benefited from his advice and encouragement; he nurtured a whole school of pianists, giving his time with a generosity that has rarely been matched. He never asked for any fees. Towards the end of his life, one Liszt pupil, the great pianist Moriz Rosenthal (whose recordings attest to his prodigious gifts), summed up Liszt thus: ‘He was more wonderful than anybody I have ever known.’

His final triumph was a visit to England in 1886. Though aged and suffering from dropsy, he gave some public concerts again, including a private recital at Windsor Castle for Queen Victoria. He attended a performance of his oratorio St Elizabeth. The reception given to him wherever he went moved him deeply and he stayed on an extra week before travelling to Bayreuth for the festival. During a performance of Tristan and Isolde he had to be taken from the auditorium: pneumonia had set in, swiftly followed by congestion of the lungs. The last word he uttered was ‘Tristan’.

Gramophone Classical Music Podcast: Liszt episodes

Liszt's piano music, with Alexander Ullman

Charles Owen on the Swiss book of Liszt's Années de pèlerinage

Benjamin Grosvenor on the piano music of Liszt

Liszt's piano music: Joseph Moog

Liszt the pianist, with Dejan Lazic

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.