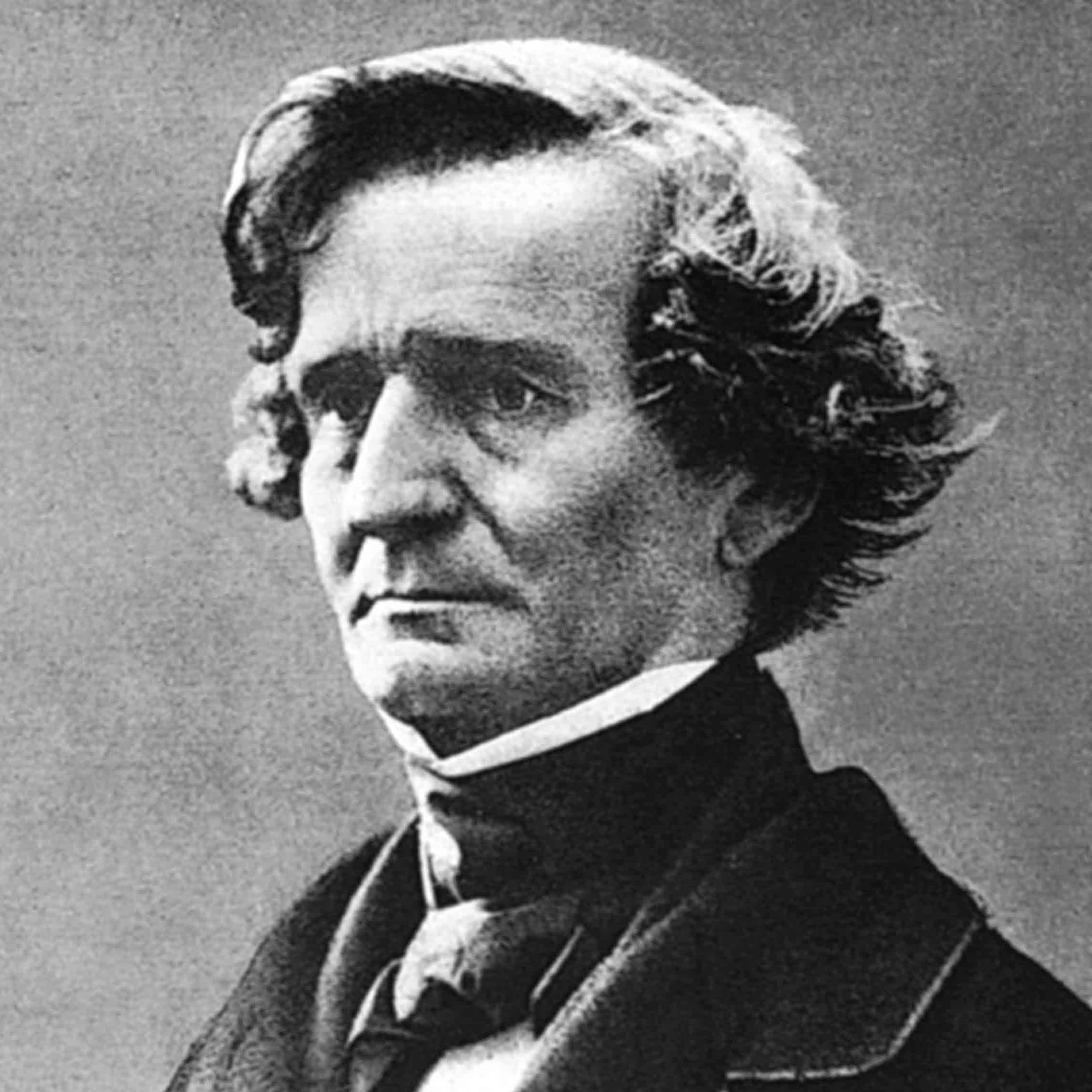

Berlioz

Born: 1803

Died: 1869

Hector Berlioz

Hector Berlioz (born December 11, 1803; died March 8, 1869) was the arch-Romantic composer, his life was all you’d expect – by turn turbulent and passionate, ecstatic and melancholic.

Quick links

Hector Berlioz: music's great revolutionary

Tim Ashley is joined by four great advocates of the composer to celebrate the self-taught, revolutionary musician whose eccentric genius is – particularly in France – only now being fully recognised... Read the article

Top 10 Berlioz recordings

Ten great Berlioz recordings by Sir Colin Davis, John Nelson, Régine Crespin, Robin Ticciati and more... Explore the list

Hector Berlioz: a biography

Berlioz’s father was a country doctor practising near Grenoble who was musical enough to give his son his first lessons on the flute, though dead set against music as a career. (Later Berlioz took up the guitar but, unusually for a composer, he never became proficient on any instrument.)

At his father’s behest, he entered the school of medicine in Paris in 1821 in order to become a doctor, taking private music lessons the while from Jean François Le Sueur. In 1824 he abandoned his medical studies in order to devote himself entirely to music and, aged 22, enrolled at the Paris Conservatoire where Le Sueur taught him composition and Antonín Reicha counterpoint and fugue.

In September 1827 Berlioz became infatuated with an Irish actress named Harriet Smithson after he’d seen her as Ophelia in a production of Hamlet given in Paris. Berlioz knew no English (Miss Smithson knew no French) and his attempts to contact her met with no success; he bombarded her with love letters which at first startled her and then terrified her; he put on a concert of his works to impress her; he rented rooms near her – all to no avail. Instead, he transferred his affections to a young pianist, Camille Moke, who became a kind of surrogate Harriet. During the next three years, Berlioz worked on a symphony, a musical autobiography, a gigantic love letter to the real object of his affections which turned out to be his most enduring masterpiece, the Symphonie fantastique. It received its first performance at the Paris Conservatoire in December 1830, a date Berlioz timed to the return to Paris of his grande passion. The work was given to great acclaim, though Miss Smithson was not present at the occasion. ‘Alas,’ wrote Berlioz, ‘I learnt afterwards that, absorbed in her own brilliant career, she never even heard of my name, my struggles, my concert, or my success!’ What that astute critic Robert Schumann wrote of Berlioz the musician was equally true of Berlioz the man: ‘Berlioz does not try to be pleasing and elegant; what he hates, he grasps fiercely by the hair; what he loves, he almost crushes in his fervour.’

The ultimate accolade for a student of music was to win the Prix de Rome, awarded since 1803 by the French Academy of Fine Arts. The recipient was entitled to study gratis in Rome for four years, living at the Villa Medici. Berlioz’s first effort was rejected in 1827; his second effort in 1828 won second prize; he tried again in 1829 but no awards were given that year. Finally, at the fourth attempt, he won the prize with his La mort de Sardanapale, though it was so poorly performed that Berlioz angrily threw the score at the musicians.

He duly set off for Italy in 1830. It proved to be a disaster. Not one to take kindly to prescribed musical rules, Berlioz also disliked the food and the music. When rumours reached him that Camille had taken a lover, he was incandescent with rage and left Rome for Paris, disguising himself as a lady’s maid, intent on killing both Camille and her amour. In Genoa, however, he lost his disguise and the wait for a replacement gave him time to cool down. He returned meekly to Rome.

Returning to Paris in 1832, he discovered Harriet was also in the city again and arranged a second performance of the Symphonie fantastique for her. This time, the bewildered actress came, heard and was conquered. After a feverish courtship Berlioz and Harriet Smithson were married in October 1833. ‘We trust,’ wrote the ungallant Court Journal, ‘this marriage will ensure the happiness of an amiable young woman, as well as secure us against her reappearance on the English boards.’ Predictably, the union was not a success and, after a volatile few years spent in poverty, they decided to live apart. Berlioz took up with a second-rate singer called Marie Recio but he never quite forgot Harriet and, towards the end of her life when she had become an invalid, Berlioz was solicitous and tender in her predicament. She died in March 1853. A year later, Berlioz married Marie, a scarcely more successful partnership in which he again outlived his wife.

The same concert that brought Harriet and Berlioz together brought an important benefactor to the impoverished composer. Niccolò Paganini, then at the height of his considerable fame, commissioned a work for his newly acquired viola. The result was Harold en Italie, inspired by Byron’s poem ‘Childe Harold’, but whereas Paganini had hoped for a virtuoso vehicle for this unusual combination, Berlioz wrote a symphony with a viola obbligato – it would not produce the effect Paganini needed and he never played it. Throughout the following two decades, Berlioz composed industriously, controversial (for, after all, he was the avant-garde of his day) and increasingly successful. Commissions came from the government, he became a music critic (from 1833 to 1863 he wrote for the influential Journal des Débats) and began his career as a conductor. In 1838, so legend has it, Paganini turned up again in Berlioz’s life: after a performance of the rejected viola concerto on December 16, the great violinist appeared on stage and knelt in homage to him, overwhelmed by hearing for the first time the work he had commissioned. The next day, he sent a message to Berlioz: ‘Beethoven is dead and Berlioz alone can revive him.’ With it came a cheque for 20,000 francs.

The money enabled Berlioz to write the ambitious work he had dreamt of – the dramatic symphony Romeo and Juliet in which he wanted to relive his first feelings of love on seeing Harriet Smithson. The work was given its premiere the following November and in the audience was a young, unknown composer called Richard Wagner. It took him by storm and ‘impetuously fanned the flame of my personal feeling for music and poetry’.

With another government commission for a large-scale work (Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale), Berlioz entered into a period of unsurpassed grandeur and grandiloquence in terms of orchestral writing. The large forces he employed to play his works (and those of others) had never been assembled before. Such excesses prompted a barrage of ridicule from sceptical critics and caricaturists. It’s said that he conducted the Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale with a drawn sword while marching through the streets of Paris; in 1844 he conducted a concert including Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony with 36 double basses, Weber’s overture to Der Freischütz with 24 horns and Moses’ Prayer (from Rossini’s opera) with 25 harps – 1022 performers in all. This was exceeded in 1855 by an orchestra, military band and chorus of 1200 for his celebratory L’Impériale.

Tours of England and Russia ensued, a festival of his music at Weimar (produced by the ever-generous Liszt) was given in 1852, opera and stage compositions flowed from him – it looks like the portrait of a successful, admired composer. Yet Berlioz had no cult following, unlike Wagner and Liszt; he wrote no solo works with which his name could appear regularly on concert programmes; he had enormous difficulty in seeing his operas and stage works mounted regularly. The final years of Berlioz’s life were miserable: he believed he was a failure as a composer and conductor in his own country; he knew his most productive days were over – a fact that deeply depressed him; his health began to give out and his marriage was unhappy. The death of his only child (a son from his marriage to Harriet Smithson) of yellow fever in Havana came as a final blow.

At his funeral, his body was carried by Gounod, Ambroise Thomas and other famous French musicians to its final resting place in Montmartre. The music was his own funeral march from the Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.