Was Rachmaninov the most complete musician of the past 150 years?

Jeremy Nicholas

Thursday, February 2, 2023

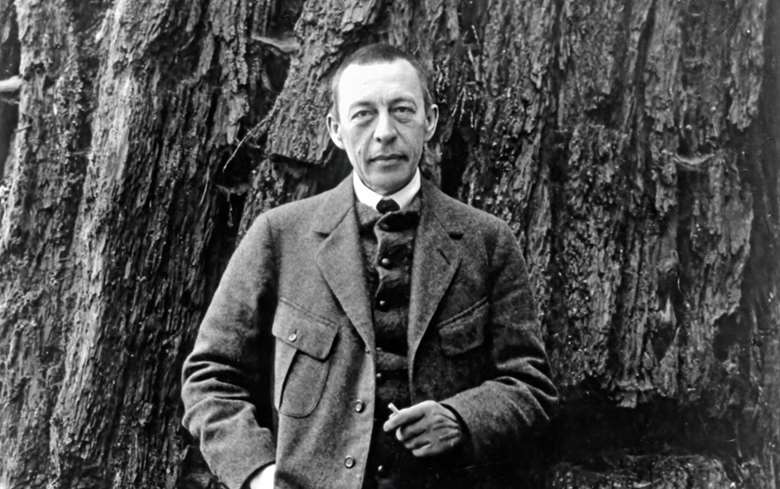

Sergey Rachmaninov was a remarkable artist who excelled as composer, conductor and pianist

Rachmaninov was perhaps the most complete musician of the past 150 years. He is someone who operated at the highest level in three different disciplines: conducting, composing and piano playing. Examples of great instrumentalists who became great conductors are too numerous to list, but few also achieved equal eminence as composers. There are myriad pianists who were also composers, but how many were also famous conductors? Lastly, one struggles to name any composer who was equally successful as a conductor and an international concert pianist.

See also:

What is the first thing that comes to mind when Rachmaninov’s name crops up? For some people, it is the way he looked: that close-shaven head, the lugubrious features and his statuesque bearing. Stravinsky’s silly quip, ‘He was a six-and-a-half-foot scowl,’ suggests a gloomy, forbidding personality – and as a young man he was certainly dour and taciturn, refusing to be pushed around even by his revered teacher Nikolay Zverev. But when listening to many of his recordings, it is impossible not to recognise a personality brimming with humour and mischief (try the tongue-in-cheek endings of Chopin’s E minor Waltz and Mendelssohn’s Spinning Song).

Stravinsky’s quip, ‘He was a six-and-a-halffoot scowl’, suggests a forbidding personality … but his music is imbued with high spirits, joy

His music is imbued with nostalgia, heartbreak, yearning, yes, but also indomitable optimism, high spirits and joy. Home videos and photos show a playful family man. The second part of that Stravinsky quote should be better known: ‘He was an awesome man … His silence looms as a noble contrast to the self-approbations which are the only conversation of all performing and most other musicians. And, he was the only pianist I have ever seen who did not grimace. That is a great deal.’

The Composer

For many, Rachmaninov means his Second Piano Concerto, one of the most beloved works in the entire classical music canon, and by far his most frequently played and recorded work. Audiences the world over love it for its lush orchestration, its string of memorable themes and the sheer, overwhelming emotion of it all. Only musical snobs and the poor souls who laugh at Brief Encounter demur. For others, Rachmaninov means the celebrated Prelude in C sharp minor, his most popular solo piano piece, sold to a publisher by the young composer for a few roubles. It made his name but became a millstone when audiences insisted he play it in every recital.

What he said about his works shows he had to be in touch with his innermost feelings to create what he created

Daniel Grimwood‘Henselt taught Zverev taught Rachmaninov,’ points out the pianist-musicologist Daniel Grimwood. ‘So you have Henselt, a composer who wasn’t Russian but was adopted by Russia, and, as his grandpupil, a composer who remained Russian but left Russia. You find a lot of Henselt in Rachmaninov. If you listen to the Henselt Concerto and then listen to Rachmaninov’s Second, you think, “Ah, that’s where he got that idea from.” And in every movement of the Henselt Concerto, quite prominently displayed, are the first three notes of Rachmaninov’s C sharp minor Prelude.’

Rachmaninov onboard ship to America (Tully Potter Collection)

Henselt’s once-ubiquitous concerto was a work with which the young Sergey would have been all too familiar. And it is piano music with which most people primarily associate Rachmaninov. There are few major pianists who don’t have any Rachmaninov in their repertoire (Brendel and Barenboim arguably being the most prominent). Frequently, the sheer physical difficulty puts it beyond the reach of many players because of the stretches involved. Rachmaninov had enormous hands and, of course, wrote for them. He could hit a 13th cleanly, which needs a span of 12 inches. The pianist Cyril Smith affirmed that Rachmaninov could ‘with his left hand stretch C–E flat–G–C–G, while his right could manage C (2nd finger)–E–G–C–E (thumb under)’.

Most pianists play one or more of the four piano concertos and the ever-popular Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. Various preludes from the two sets he wrote (Opp 23 and 32) are familiar (if not always identifiable by name). Other works – such as Piano Sonata No 2, the Moments musicaux and the Suite No 2 for two pianos – are regularly heard. Then there’s the Cello Sonata, and the E minor Second Symphony, with a slow movement that can reduce the stoniest critic to tears. Vocalise is the best known and surely the most moving of all his songs.

Rachmaninov used unashamedly 19th-century models for his art, reason enough for the snootier critics to dismiss him

Yet, rather like Liszt and Saint-Saëns, Rachmaninov is known for a tiny fraction of his output. Grimwood agrees: ‘His output isn’t particularly gigantic, but it’s big enough. People hand out judgements on his music without knowing the Corelli Variations, the Études-tableaux or any of the stage works. They are not known by the general public because it is Rachmaninov not doing what people want him to be doing. They want him to be doing Piano Concerto No 2 all of the time. He was absolutely steeped in opera. For me, one of his greatest works is The Miserly Knight. It is totally original. There are no female voices. There’s virtually no action; no chorus. It’s riveting from beginning to end – one of the most pessimistic pieces of music ever written! He is essentially a man of the theatre, so his music is always narrative.’

To The Miserly Knight and his student opera Aleko we must add his choral masterpiece The Bells and the All-Night Vigil (aka Vespers), The Isle of the Dead, Symphony No 3 and, perhaps above all, the Symphonic Dances. ‘Think of the second of the Symphonic Dances and what that has given to film music,’ says Grimwood. ‘It’s a different route into what is now our modern world without being troubled by the avant-garde or the serial or anything else foreign to his nature.’

Rachmaninov used unashamedly 19th-century models for his art, reason enough for the snootier critics to dismiss him. Piano Concerto No 2 was, for Paul Rosenfeld, ‘a little too much like a mournful banqueting on jam and honey’; Symphony No 2 was dismissed by Virgil Thomson as ‘mud and sugar’. Most famous was the notorious entry on Rachmaninov in the 1954 edition of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians comparing him unfavourably with the Balakirev school, Taneyev and Medtner, prophesying that, ‘The enormous popular success some few of Rachmaninoff’s works had in his lifetime is not likely to last, and musicians never regarded it with much favour.’ As Grimwood explains, ‘Prevailing fashions meant nothing to Rachmaninov. If you’re going to listen with a prejudiced ear, you’re going to miss the point if you don’t take his music on its own terms.’

The Conductor

Until he left Russia in 1917, Rachmaninov was best known as a composer and conductor. Today, he is less well remembered for the latter (only three recordings were made with him in that role: The Isle of the Dead, the orchestral version of Vocalise and Symphony No 3), but his first important conducting post was two seasons (1904-06) with the Bolshoi Theatre. During his visit to the US in 1909-10, he gave 19 performances as pianist and seven as conductor with the Boston SO. He was offered conductorship of the orchestra but declined. His most influential conducting post was with the Moscow Philharmonic Society (1911-13).

After his beloved Ivanovka estate was confiscated by the communist authorities, it became clear that he could survive in Russia no longer. Unexpectedly, he was offered a tour of 10 piano recitals in Scandinavia, providing the perfect excuse for him and his family to obtain permits and leave the country in December 1917.

During that tour, he was made three offers: conductorships of the Cincinnati and (again) Boston symphony orchestras, and 25 piano recitals. He turned down the conducting offers to pursue the career of a piano virtuoso. After his departure from Russia, he all but stopped composing. His Op 39 Études-tableaux (1917) were the last completed works before he left. In his remaining 26 years, he produced just six further opuses.

The Pianist

In a 2010 poll, 100 professional pianists were asked to name their top three favourite pianists. The winner by some distance was Rachmaninov. ‘It’s a paradox’, Grimwood remarks, ‘that he was one of the great pianists of his generation, but only reluctantly. It wasn’t part of his life plan to become what he became.’

When he and his family left Russia for Scandinavia he was 44. He did not have the repertoire of peers such as Josef Hofmann and Leopold Godowsky, and played few works in public other than his own. But thanks to the ironclad technique he had acquired during his early training with Zverev, and by dint of a rigorous practice regime whereby he added to his repertoire various other pieces he had played over the years, Rachmaninov transformed his career.

Arriving in the US in November 1918, he gave his first solo recital just a few weeks later, quickly being able to establish himself as a virtuoso soloist of the highest order. For concerto engagements, he played his Second and Third frequently. The only other works for piano and orchestra that regularly featured in his recital programmes were the first concertos of Tchaikovsky and Liszt (they soon dropped by the wayside, however) and, later (after 1940), Beethoven’s First.

Unlike the generation of musicians after him, who didn’t care to wear their heart on their sleeve, Rachmaninov was unable to disconnect himself from his emotions

Apart from the pieces he recorded for Edison (1919) and then RCA Victor (1920-42), Rachmaninov’s repertoire in the 1920s and ’30s included works by Alkan (Marche funèbre, Op 26), Bach (Toccata in E minor; French Suite No 6), Balakirev (Islamey), Beethoven (Appassionata Sonata), Brahms (Ballades, Op 10 Nos 1 and 2), Chopin (Fantaisie in F minor; Rondo in E flat, Op 16), Grieg (Ballade), Liszt (Dante Sonata; Hungarian Rhapsody No 9; Venezia e Napoli), Medtner (various skazki – ‘tales’), Scriabin (Piano Sonata No 2), J Strauss II–Godowsky (Künsterleben paraphrase) and Weber–Tausig (Invitation to the Dance). The average salary in the US in 1920 was approximately $3269. A record of fees paid to artists after the First World War by the New York Philharmonic Society reveals that Rachmaninov was paid an astonishing $1500 (one website equates that to $22,350 today) for an appearance in 1920, an amount second only to the fee commanded by Jascha Heifetz the previous year: $2250.

Rachmaninov’s discography is arguably the most consistently glorious of any pianist. First, there are no failures. Secondly, it is finite. Unlike the records of many of his peers, there are no undiscovered takes gathering dust in some record company’s vaults. He had complete autonomy over which recordings were issued and which were not. The masters of any rejected takes were always destroyed at his request. Even his own copies of the shellac pressings made from those masters were destroyed (on his instructions) by his niece Sophia Satin. A handful of studio recordings including Liszt’s Rhapsodie espagnole and Weber’s Momento capriccioso were approved but never released. They seem to have vanished and are something of a Holy Grail to collectors.

There are also no known live recordings of Rachmaninov. Unlike Hofmann, Moriz Rosenthal and many pianists broadcasting in the 1930s and ’40s who were captured by home-based recording enthusiasts, nothing that Rachmaninov played for radio transmission can be heard. Why is that the case? Because he did not permit broadcasts of his live performances for fear that they might reveal a defect in his playing. Whenever a concert was being broadcast, when it came to his spot, the network was obliged to switch to his electrical recording of his Second Piano Concerto.

In 2018, Ward Marston issued a pirate recording that had circulated among collectors for many years, of Rachmaninov in 1940 demonstrating at the piano to conductor Eugene Ormandy how he wished his Symphonic Dances to be played. It’s a truly fascinating document but one wonders if Rachmaninov was aware he was being recorded. He would certainly have known nothing of the two brief excerpts from a live 1931 recital of him playing ballades by Brahms and Liszt, included in that same Marston release.

Though we must be grateful for what we have of Rachmaninov (pianist and conductor) on disc and on piano roll (35 for Ampico, 1919-29), so much more could so easily exist were it not for RCA executives. How could they have turned down an opportunity to record him and Vladimir Horowitz together in Suite No 2 and the two-piano version of the Symphonic Dances? But they did. It is one of the great losses to musical history.

Unlike the generation of musicians after him, who didn’t care to wear their heart on their sleeve, Rachmaninov was unable to disconnect himself from his emotions. ‘Everything he said about his compositions shows that he had to be in touch with his innermost feelings in order to create what he created,’ suggests Grimwood. ‘There’s a modernity in a lot of Rachmaninov that passes people by. He was one of those composers like Scriabin who linked the world of Tchaikovsky to the world of the avant-garde. He did pass on something to the next generation even if it was not in a conventional way.’ A century and a half after Rachmaninov’s birth, the popularity of his best-known works shows no sign of diminishing.

This article originally appeared in the January 2023 issue of Gramophone magazine. Life is better with great music in it – subscribe to Gramophone today