Review - Eloquence’s Piano Library

Jeremy Nicholas

Friday, January 3, 2025

Jeremy Nicholas browses through two collections of keyboard treasures

Before dipping into these two bran tubs of pianistic heaven, I must take you back more than a decade to another collection of piano discs. DG issued a 10-CD box-set bizarrely (and quite inaccurately) entitled ‘The Liszt Legacy’ (9/12). In plain white covers came the first CD releases of recordings made in the 1950s and early 1960s by Claudio Arrau, Alicia de Larrocha, Raymond Lewenthal, Benno Moiseiwitsch and Egon Petri originally issued on the Westminster and American Decca labels. (Arrau was the only one among them to have inherited the echt ‘Liszt Legacy’, his teacher Martin Krause having studied with the great man.)

All 10 CDs, though, were highly desirable, with all sorts of goodies: the two devoted to Lewenthal had two sets of Scriabin Preludes, a selection of popular encores and 11 toccatas by various composers; Petri dazzled in Liszt transcriptions and in original works and Bach arrangements by his mentor Ferruccio Busoni; there was elderly Benno Moiseiwitsch in Schumann (Carnaval, Kreisleriana, Kinderszenen), his own arrangement of Mussorgsky’s Pictures and some Beethoven – the great man’s final studio sessions. These constituted six of the 10 CDs. No collection should be without them.

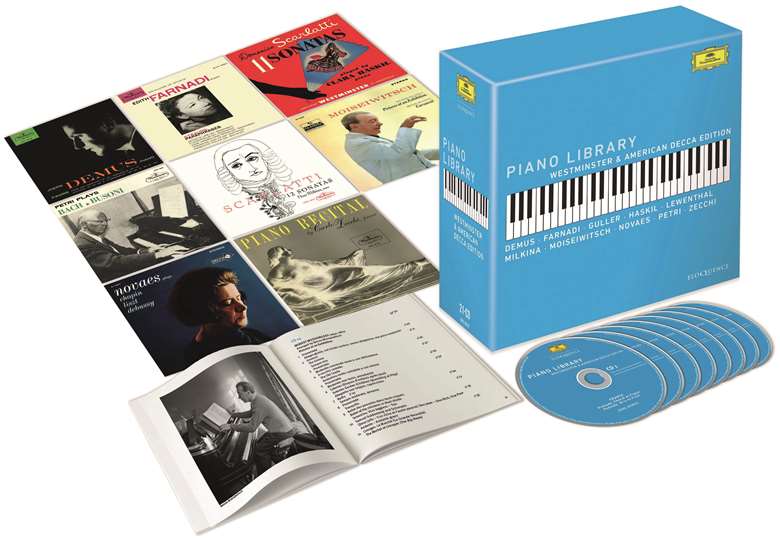

These six discs reappear in this new 21‑CD box-set entitled – more accurately, if more prosaically – ‘Piano Library: Westminster & American Decca Edition’. The only difference between what you might already have in ‘The Liszt Legacy’, apart from some changes in running orders, is that all the discs are now presented in mini-reproductions of the original LP covers. It’s like seeing photographs of old friends. However, for some reason the two Arrau and two de Larrocha CDs are not included. So if you now ditch ‘The Liszt Legacy’ you will lose Arrau in four Beethoven sonatas and Chopin’s Fantaisie (all from 1954 and hitherto previously unreleased in any format), and de Larrocha in fascinating albums from 1955 and 1956 in which she plays Turina, Mompou and Granados, including her first and, arguably, finest traversal of Goyescas.

The new Piano Library set also takes the opportunity to add more Lewenthal: the first release on CD of three Beethoven sonatas (Pathétique, Moonlight and Appassionata) and seven short ‘these you have loved’ encores by Beethoven, Brahms, Chopin and Schumann. Arguably of greater significance, in addition to the wonderful Petri discs of Liszt and Busoni, we now have the first CD releases of his 1956 recordings of the same three titled Beethoven sonatas recorded by Lewenthal, plus the Hammerklavier. The latter, one of Petri’s ‘party pieces’ and which he had previously recorded for American Columbia, while not technically perfect, is a tremendously impressive reading of great individuality and insight. The producer of both Beethoven discs was, I note, the fledgling Charles Gerhardt.

The chief USP of the set – apart from the quality of playing and the legendary names – is that almost all the recordings have never previously been released on CD. Some have not been available for the best part of 70 years. Better late than never. The CDs are arranged in alphabetical order of pianist beginning with D for the Austrian Jörg – Joerg on the LP sleeve – Demus (1928-2019). Though recorded on an indifferent piano, Franck’s Prelude, Chorale and Fugue and Prelude, Aria and Finale are given heartfelt accounts on one disc – the Chorale is memorable, like listening to tiny waves lapping the shores of a lake – and on the other a selection of Fauré, a second composer not usually associated with Demus.

F is for Edith Farnadi (1911‑73). Why is this wonderful artist not celebrated more widely? Still waiting for CD release are outstanding accounts of Liszt, Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky and Bartók concertos, plus myriad solo Liszt recordings that really deserve their place in the sun. Meantime, we must content ourselves with the first-ever recording of the complete Schubert-Liszt Soirées de Vienne, still a rarity on disc (No 6 is the only famous one and, frankly, with good reason) and the earliest recordings of three J Strauss II-Godowsky paraphrases (or symphonic metamorphoses, as he called them). Unusually, all three are played without any cuts and with every repeat observed. Seventy years on, they remain among the finest of all Godowsky recordings. Farnadi tops these off with two further ear-tickling Strauss transcriptions by Dohnányi and Schulhoff.

There are two discs of Scarlatti sonatas. One, unpredictably, is from Clara Haskil (her only recording for the Westminster label, made, so Mark Ainley’s absorbing booklet tells us, on Sunday, October 1, 1950). Most of the 11 sonatas will be unfamiliar – Kk193 in E flat is a gem. The LP’s brief course (c37 minutes) is extended on the CD by the addition of three previously unpublished Chopin mazurkas recorded for American Decca in 1951 by Youra Guller. Rare they may be, but of limited musical interest. The other disc of Scarlatti sonatas (12 of them) is from the Moscow-born Matthay pupil Nina Milkina (1919-2006), whose second disc here is devoted to four keyboard sonatas by CPE Bach. I value these two as highly as anything else in the collection. The playing is simply enchanting – unmannered, witty, radiating pure love of the music – and extraordinarily well recorded.

Two other rare LPs are the sole recordings the artists made for the label. Carlo Zecchi (1903‑84), in his only long-playing disc, gives us a recital programme of Scarlatti, Bach, Mozart, Chopin and Schumann (Kinderszenen). Lovely to have, but I don’t hear a big personality at work, something that cannot be said of the great Guiomar Novaes (1895-1979) in her robust Chopin (Barcarolle) and a selection of four Debussy pieces. Best of all are Liszt’s two Études de concert, a Liebestraum No 3 that reminds you that it is a song transcription and a Hungarian Rhapsody No 10 with deliciously executed glissandos.

So much for the ‘Westminster & American Decca Edition’. Its companion is the 22-CD set ‘Piano Library: Deutsche Grammophon Edition’. Its raison d’être is quite different from its stablemate and its interest less consistent – both in terms of artists and performances. Jonathan Summers in his accompanying booklet explains that most of the discs were the result of competition wins. Eight of them were recorded between 1978 and 1980, LPs issued by DG in the ‘Concours’ series of live performances with either a morning rehearsal or repeat public performance also recorded for patching. Another subtitled series set up by DG was named ‘Debut’, aimed at helping young artists at the beginning of their careers.

Once again, the pianists are presented in (more or less) alphabetical order. By far and away the most famous name among the 21 happens to begin with A. It may be that disc 1 will be sufficient reason to invest, for here is Vladimir Ashkenazy recorded live at the fifth International Chopin Competition (1955) playing Chopin’s F minor Concerto, Ballade No 2, a couple of études and mazurkas and rounding off with Scherzo No 4. (Adam Harasiewicz won first prize, Ashkenazy came second, Fou Ts’ong third.) Those two LPs on the Heliodor label (remember that?) are presented here in their original mono state. The CD is made up with a selection of six of Rachmaninov’s Études-tableaux, Op 33, recorded live in Warsaw in 1956 by Lev Oborin, who had won the Chopin Competition in 1927, another mono Heliodor release and itself originally a filler for a Rostropovich album.

Oborin (1907-74) was a major Soviet artist with a long career. Others were not so fortunate. The hugely gifted Dino Ciani was killed in a car crash in 1974 at the age of 32. He is remembered here in two fine studio performances from 1970 of Weber’s rarely played Sonatas Nos 2 and 3 (fascinating to compare his far more expansive view of the former with its 1939 recording by his teacher Cortot). Youri Egorov left us in 1988 aged 33 due to complications from Aids. You can hear why he was so highly regarded in live performances of Prokofiev (Sonata No 6), Brahms (Paganini Variations) and Schumann (Carnaval). The South African pianist Steven De Groote (1953‑89), winner of the Leventritt Competition in 1976 and the Van Cliburn in 1977, died four years after miraculously surviving the severe crash of the plane he was piloting. His live recordings of Beethoven’s Eroica Variations and Schumann’s Études symphoniques from 1978 are on disc 7.

Those blessed with longer lives include Veronica Jochum von Moltke, eldest daughter of conductor Eugen Jochum, still with us at the age of 97. Her 1963 recordings of Schumann’s Sonata No 2, Novelletten and Drei Fantasiestücke, Op 111, have never previously been released on CD. The four Nachtstücke, Op 23, omitted from the DG LP because of lack of space, are published here for the first time in any format. Elly Ney (1882-1968) is, second to Ashkenazy, the other big name here, infamous for her support of the Nazi party during the 1930s and the Second World War, something I always find difficult to forget even when I’m listening to such illuminating and, yes, noble performances of Beethoven’s Pathétique, Moonlight, Appassionata and Op 110 sonatas.

Other names have faded from view entirely: Mikhaïl Faerman, Diana Kacso, David Lively, Alexander Lonquich and Zola Mae Shaulis (a magnificently brisk Goldberg Variations without repeats, Prokofiev’s Sonata No 7 and five Bach Toccatas, BWV911‑915). Brief accounts of all their careers are in the booklet. One mystery is the career of the Cuban pianist Jorge Luis Prats (b1956), one of the mighty technicians of the age, and surely one of the most laid back. His single LP for DG was made in 1979 – Beethoven Sonata Op 101, Schumann Toccata and Ravel Gaspard de la nuit, a Prats speciality. Why no more? Why is he not signed to a label? Why is he not better known? If this box illustrates nothing else, it is that competition wins do not necessarily a career make, and that the road to success as a concert pianist can be a remarkably rocky one.