Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No 2: a guide to the best recordings

Jeremy Nicholas

Monday, May 13, 2024

Tchaikovsky’s Second Piano Concerto has long lived in the shadow of its ubiquitous predecessor and fallen victim to well-meaning editorial excisions. Jeremy Nicholas assesses its eight-decade discography

Ihave to start on a personal note. Decades ago, I had no idea that Tchaikovsky had written more than one piano concerto. Then one day I alighted on an LP announcing not only a second Tchaikovsky piano concerto but a third. Pianist – Gary Graffman. Conductor – Eugene Ormandy. I bought it, played it and fell in love with both works.

Often, when you hear something for the first time it becomes your benchmark, and so it was with this recording of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No 2 … until I learnt many years later that what I had been happily listening to all that time was not the full score. For the first 60 years after the publication of the Second Concerto, Graffman and Ormandy, like almost everyone else, played what is known as the Siloti version. Because this was issued with the imprimatur of the composer, musicians everywhere understandably assumed that this score contained nothing but the authentic final thoughts of Tchaikovsky.

There are basically two versions of ‘Tchaik 2’ sanctioned by the composer – one with no cuts, the other with cuts authorised and agreed by Tchaikovsky. This survey focuses on the former, but the Siloti version, like it or not, is part of the history of the work and must be considered.

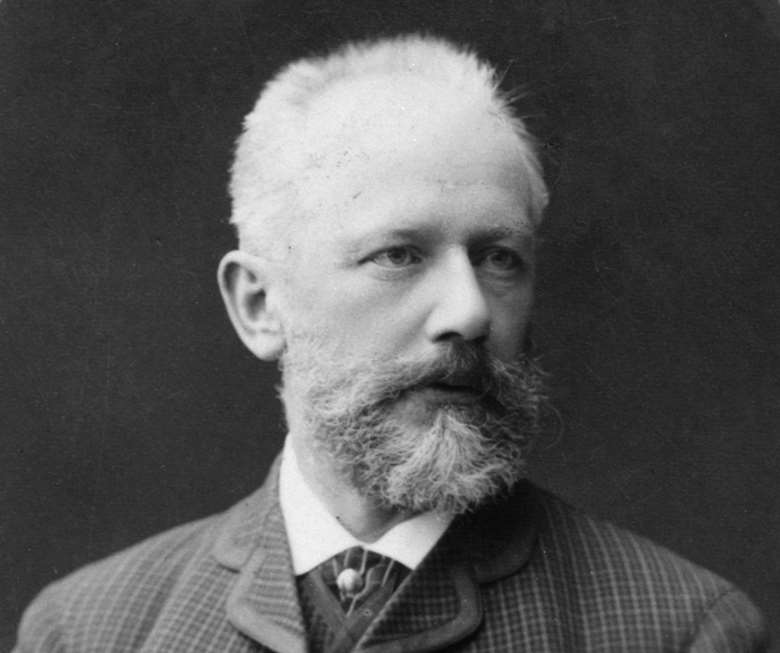

Siloti radically revised the work; Tchaikovsky didn’t approve all the changes (photography: Fine Art Images / Bridgeman Images)

The chronology of the concerto’s creation is easy to follow. Tchaikovsky began it on October 10, 1879, and sketched the first movement in 10 days and the finale during November. In mid-December he wrote that ‘the sketch of my concerto is now complete and I am very satisfied with it, especially the second half of the Andante’ (my italics). The orchestration was complete by April 28, 1880, and the concerto was dedicated to Nikolay Rubinstein (despite the critical mauling the latter had handed out to the First Piano Concerto, of which Rubinstein had since become a major champion). The score and orchestral parts were published by Jurgenson in February 1881. Less than a month later, Rubinstein died. The premiere was now entrusted to Sergey Taneyev and took place on May 18, 1882, under the baton of Anton Rubinstein.

In late 1888 Tchaikovsky himself conducted performances in St Petersburg, Prague and Moscow with Vasily Sapelnikov. For these, he made three small cuts: in the first movement, bars 319‑42; and in the Andante, bars 247‑81 and 310‑26. These are the only cuts we know for definite that he sanctioned. Then, in 1893, Jurgenson entrusted to Alexander Siloti the job of editing the concerto’s republication. Siloti (1863-1945), pianist, composer and prolific transcriber, was also Rachmaninov’s cousin. Not only did Siloti propose revising and simplifying the piano part but radically altering the formal structure of the first and especially second movements. Tchaikovsky wrote to Jurgenson in August 1893 saying that he had agreed to certain of Siloti’s changes but there were others that he quite definitely could not accept. ‘He is overdoing it in his desire to make this concerto easy, and wants me to literally mutilate it for the sake of simplicity. The concessions I have already made and the cuts which both he and I have introduced are quite sufficient … There will be no great changes – it will be a matter of cuts only.’

Tchaikovsky died three months later without ever seeing the revised publication. It appeared in 1897 with all the rewrites, alterations and cuts to which Tchaikovsky had objected. Unforgivably, Jurgenson issued it as ‘Nouvelle édition, revue et diminuée d’après les indications de l’auteur par A Ziloti’. (Interesting to read a letter written by Josef Hofmann in 1924 advising the Curtis Institute not to employ him: ‘In my opinion Siloti is a musical joke.’)

One recording gives you the opportunity of being able to compare both versions of the slow movement on the same disc. That comes from Stephen Hough with the Minnesota Orchestra under Osmo Vänskä. You can tell how much music Siloti slashed from the Andante (second movement) by looking at the timings: 13'27" in Tchaikovsky’s original; a mere 7'06" in Siloti’s abridgement. From its first performances, there had been criticism over this movement. In what is one of Tchaikovsky’s most expressive and heartfelt slow movements, it is almost as though the piano had been demoted to an accompanying role, dominated not by the soloist but by the duetting of a solo violin and solo cello.

While Siloti’s solution was far too drastic, there was an inherent problem with the structure, which Tchaikovsky himself recognised. Hough offers his own solution to the problem in a third version of the Andante. This, in his words, gives ‘a symmetry to the whole movement, lending a psychological cohesion, and obviating the need to remove any music’. Hyperion’s release, which also includes the Piano Concertos No 1 and 3, the Concert Fantasia, Op 56, and a couple of Hough’s solo song transcriptions, is an important reference point. All the works receive thrilling live performances and if your introduction to these works was through them, you would be fortunate indeed. My only cavil is over the last section of the finale of No 2, where clarity is sacrificed for speed. It sounds like an adrenalin rush – highly effective, I’m sure, if you were there in the audience but disconcerting for repeated listening (it is, after all, marked l’istesso tempo). Still, Hough’s performance, dating from 2009, is a classic.

The earliest recordings

The G major Concerto was recorded just three times in the 78rpm era. The earliest was the great Benno Moiseiwitsch in August 1944 with the Liverpool Philharmonic and George Weldon standing in for an indisposed Malcolm Sargent. The opening Schumannesque subject is far from Allegro brillante e molto vivace, more maestoso e pesante. In fact, many of the older recordings begin like this – four-to-a-bar instead of the more alert two-in-a-bar. Nevertheless, Moiseiwitsch carries all before him – until, that is, the first movement’s massive second cadenza. Not only is this abbreviated with the help of someone’s dreadful Tchaikovsky pastiche but the orchestra’s tutti re-entry is, calamitously, played by the soloist, a terrible decision that not even Siloti would have countenanced. Siloti’s abbreviated Andante (Moiseiwitsch is not above adding some left-hand thirds of his own to the mini-cadenza) is followed by the full finale with Moiseiwitsch’s rewritten final bars.

Apart from cutting swathes of the first and second movements, Eileen Joyce in May 1946 also decided to write her own ending (she does not even finish on Tchaikovsky’s unison tonic minim). She and the LPO under Grzegorz Fitelberg were recorded in better sound (it was Joyce’s first outing on Decca) but for some reason the performance was not issued until 2017 in the 10-CD set of her complete studio recordings.

Also from 1946 is the little-known (until its release on APR last year) recording by Shura Cherkassky with the Santa Monica Symphony Orchestra under Jacques Rachmilovich. As I wrote at the time, ‘though it is a compelling performance from the soloist, daring, constantly pushing forwards, electrifying at times, impulsive at others, [it] fails on three counts: the less than ideal acoustic of the Los Angeles venue, the undernourished Santa Monica Symphony and the savage cuts of the Siloti edition’. Cherkassky it is who is largely responsible for the work’s return to the (fringes of the) repertoire, for it was one he championed throughout his career.

The LP era

In his famous 1955 recording with the Berlin Philharmonic under Richard Kraus, Cherkassky displays the same lightness of touch, clarity of texture and characteristic charm as on the shellac recording (the two first-movement cadenzas are superbly articulated and nuanced – not simply a fast finger-fest). The Andante is a mish-mash of authorised Tchaikovsky and some (but not all) of the Siloti cuts. It’s a pity, because the playing is exquisitely expressive and entirely convincing, and in the finale every note has clarity and purpose – a rare achievement. As Trevor Harvey said in his 1956 review, ‘the opportunity of hearing such piano-playing should not be missed’.

Cherkassky’s third iteration of the concerto was made in 1981 with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and Walter Susskind, whose final recording it was. The Siloti cuts notwithstanding, I would rather hear Cherkassky in the theme of the slow movement of this concerto than anyone else.

Another Siloti version comes from Emil Gilels, recorded in 1973 with Lorin Maazel. Unlike Moiseiwitsch and Cherkassky, he opens proceedings with some urgency. The first movement is pianistically thrilling, the second comes nowhere near the expressiveness of Cherkassky and the finale is unattractively heavy-handed.

Stephen Hough recording Tchaikovsky with the Minnesota Orchestra and Osmo Vänskä in 2009 (photography: Greg Helgeson)

Despite the dated Melodiya sound, I prefer his pupil Igor Zhukov (1936-2018) with the Moscow Radio Large Symphony Orchestra and Gennady Rozhdestvensky, recorded in 1969. He takes a similar view of the finale but captures the exciting theatricality of the first movement like few others and plays the full score. Available intermittently on disc, it can be viewed on YouTube.

The latest (last?) Siloti version I have come across was made in 2012 by Simon Trpčeski (well aware the cut score was by then an anachronism) with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra under Vasily Petrenko. Here the Andante sounds almost perfunctory but the close working relationship between soloist and conductor in the outer movements is palpable, and the final pages are very exciting. Arguably the best recorded sound for the Siloti version.

The first artist to record the full score (c1951) was Tatiana Nikolayeva in a reading that is thus of some discographical importance. It’s an impressive account, with good tempos and tempo relationships, even though inevitably the sound quality is not exactly state-of-the-art. What militates against its inclusion in the top echelon is the quite insensitive re-entry of the violin and cello after the più mosso section of the slow movement, the very section that listeners were hearing for the first time on disc. Also, the tuning of the piano’s high D natural in the finale becomes a more noticeable defect as the movement progresses.

The digital age

I know many rate Mikhail Pletnev’s 1990 version highly. Fabulous technique, everything tossed off with enviable ease, big paragraphs, long phrases, pushing forwards constantly, and the accompaniment from Vladimir Fedoseyev and the Philharmonia is first class (stylish woodwind-playing), but bravura passages pass by in a meaningless blur. The Andante features a saccharine violin soloist with a narrow vibrato that I didn’t care for. Finally, speed here does not equal excitement. I found it all a bit showy and heartless.

Oleg Marshev’s account dates from 2002. His Tchaikovsky on Danacord is a good option if you want the convenience of all six works for piano and orchestra on a two-disc set (it even includes the brief Allegro in A minor for piano and strings). There are drawbacks: the recorded balance frequently favours the vin ordinaire Aalborg Symphony Orchestra at the expense of the soloist; the brass section sounds underpowered; and, despite two fine soloists in the Andante, the sluggish tempo elongates the movement to nearly 17 minutes.

Yet another Russian take comes from Denis Matsuev and Valery Gergiev (with the Mariinsky Orchestra back in 2013). The back of the CD informs us that ‘Piano Concerto No 2 is performed using Tchaikovsky’s revised version’. And so it is for the most part until the first beats of alternating bars in the first cadenza (bar 267 et seq), which Matsuev unaccountably changes from quaver/quaver rests to minims. All tension evaporates. Everything then goes swimmingly until the second cadenza, in which he makes an ugly and needless cut of 16 bars leading into the big tutti restatement of the first subject. Not good. A shame, because the slow movement is ravishing, the finale sparkling if somewhat impatient.

Kirill Gerstein: a soloist on fire, but not at the expense of clarity or thoughtful phrasing (photography: Marco Borggreve)

Ivan March thought Peter Donohoe’s account with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra under Rudolf Barshai ‘one of the great Tchaikovsky records, bringing a new dimension to the score … brilliantly vivid and full-bodied in the orchestra …set in an ideal recording relationship with the richly coloured backcloth’ (11/88). His review heralded a 1988 Gramophone Award. Is the piano a little glassy-toned? No matter. The brilliance of Donohoe’s performance puts it in a different league to Matsuev and Pletnev. He also has the grace to take note of the composer’s smallest requests, such as the three pauses in the bars before the big cadenza. Few manage to use them as successfully. In the Andante he has two world-class soloists in Nigel Kennedy and Steven Isserlis.

I was similarly enthusiastic in May 2016 over the Chandos recording with the brilliant Chinese-American Xiayin Wang, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and Peter Oundjian. The outer movements are on a par with Donohoe and Barshai. Wang plays the finale with tremendous swagger and exuberance, emphasising that this is a virtuoso showpiece intended to dazzle – no more, no less. If the two soloists are not quite as expressive and characterful as Donohoe’s, the Andante rises to a powerful climax enhanced by Chandos’s technicolour sound picture. The unusual coupling is the Khachaturian Concerto.

There is one passage in the Second Concerto that moved me to tears the first time I heard it (played by Graffman and Ormandy). It comes at the end of the big first-movement cadenza when the piano seems to be heroically fighting for its life before the orchestra throws him, as it were, a lifebelt and allows him to swim safely to shore. Garrick Ohlsson with Vladimir Ashkenazy expertly piloting the Sydney Symphony had the same effect on me. It’s all to do with the pacing, timing and phrasing of this passage – three things which this team get spot-on throughout. Ashkenazy’s attention to the woodwind- and brass-writing reveals many details commonly lost, as does Ohlsson. For example, I was made aware for the first time of the string of dotted F natural minims at the outset of the first cadenza (un poco capriccioso e a tempo rubato). And when the score says fff, Ohlsson has the power and stamina to duly oblige. It’s only the lack of fuoco in the Allegro fuoco finale that slightly disappoints, but if you want to hear every note clearly – and this is, after all, a concerto for piano, not a symphony with piano accompaniment – then you will not be disappointed.

In a round-up of classic concerto recordings in 2005, I admired the account by Elisabeth Leonskaja, Kurt Masur and the New York Philharmonic. This is their 1997 recording (not their earlier one with the Gewandhaus Orchestra, which is now less easy to find). ‘Leonskaja takes no prisoners in the outer movements’, I wrote, while drawing attention to a persistent cougher in the front row of Avery Fisher Hall in this live recording. Listening again, I hardly noticed the cougher but did pick up a door opening (?) and later a moment of conversation (?) at 8'25" in the slow movement. Not enough to mar a tremendous performance – just odd.

With each recording examined for a survey like this, an increasing number of potential pitfalls and danger points emerge, moments that are missed or inaudible, or passages that are not as effectively realised as in other versions. No recording I have heard clears every single hurdle but the one that gets closest to a clear round is from the mighty Kirill Gerstein with the Czech Philharmonic and Semyon Bychkov. Recorded in an ideal acoustic, as early as bar 33 (the answering trio of horns) you know this is going to be special. Little details are attended to – such as the flute in bar 113 making sure the first beat is played as written (quaver/quaver rest) – without detracting from the big picture. Added to this, you have a soloist who is on fire, but not at the expense of clarity or thoughtful phrasing. The Andante is as heartbreaking as any without descending to sentimentality, and few versions do the question-and-answer between soloist and orchestra in the finale better. It storms to one of the most exciting codas on record.

‘In my beginning is my end.’ After all this listening, I went back to my first encounter with the Second Piano Concerto. I had not played it for a year or two, I suppose. How would it stack up after all this, albeit with Siloti’s attenuated slow movement and the composer’s sanctioned cut in the first movement? Would I think more or less of my first love? Honestly? I think I got lucky with Graffman and Ormandy. There is a warmth, depth and exhilaration in this performance that remains unequalled. Much as I admire Hough, Donohoe, Gerstein, Leonskaja, Wang and Ohlsson in their different ways, and even though I have to contend with the cuts, Graffman is the one who moves me more than any other. That’s my purely personal preference, but for the full score it’s Gerstein.

Recommended Recordings

The Siloti Version

Gary Graffman; Philadelphia Orch / Eugene Ormandy (Sony Classical)

Apart from Graffman’s superb handling of the (extremely demanding) solo part, there is the Philadelphia sound. The strings are to die for. Balance between soloist and orchestra is ideal. The recorded sound from 1965 comes up freshly minted in its latest iteration. And the Second Concerto is followed by the Third in my benchmark recording.

The Reference Version

Stephen Hough; Minnesota Orch / Osmo Vänskä (Hyperion)

Stephen Hough’s 2009 account should be in every collection, not merely because of the spellbinding live performance, the unique inclusion of the slow movement in the original, Siloti's and his own versions, plus his own transcriptions of two Tchaikovsky songs. This is the best two-disc issue of all three concertos and the Concert Fantasia.

Gramophone Awardee

Peter Donohoe; Bournemouth SO / Rudolf Barshai (Warner Classics)

If Siloti had heard the slow movement played by Donohoe, Nigel Kennedy and Steven Isserlis, he would not have wanted to cut a note. The finale simply fizzes with high spirits and pianistic bravura. Currently issued with the other piano concertos, the Concert Fantasia, the Violin Concerto and the Rococo Variations.

Top Tchaikovsky Two

Kirill Gerstein; Czech PO / Semyon Bychkov (Decca)

Gerstein and Bychkov tick all the boxes more clearly, convincingly and consistently than even the finest competition. As everyone storms into the final bars, you really do feel like standing and shouting ‘Bravo!’. It comes in a box set with all the symphonies, concertos and other works – over seven hours of Tchaikovsky, ‘a complete portrait of the composer’ as the October 2019 review put it.

This article originally appeared in the April 2024 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue – subscribe today