Schumann’s Piano Concerto: a guide to the best recordings

Jed Distler

Friday, January 3, 2025

Schumann’s sole completed piano concerto remains among his best-loved works. Jed Distler listens to a selection of the prominent pianists who have contributed to the concerto’s substantial discography

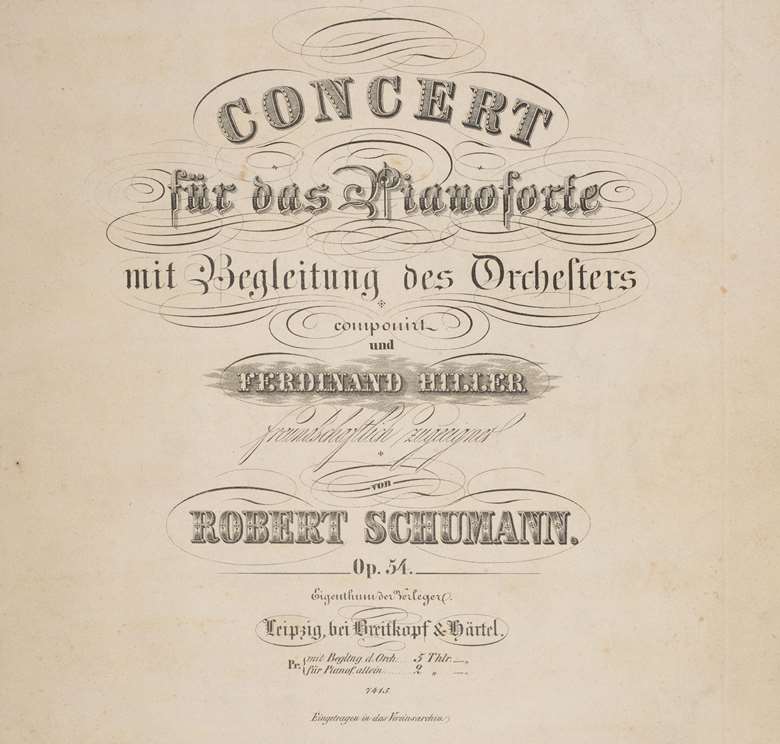

Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor began life in the form of a monothematic single-movement Phantasie for piano and orchestra, composed in 1841. After unsuccessfully offering it to the Leipzig published Kistner and Härtel, Schumann set the piece aside. He revised it four years later in 1845, adding a slow movement and finale to complete a three-movement concerto.

Prior to his 1840 marriage to pianist Clara Wieck, Schumann had mainly composed solo piano works and songs. ‘Don’t take it amiss if I tell you that I’ve been seized by the desire to encourage you to write for orchestra. Your imagination and your spirit are too great for the weak piano’, Clara wrote to Robert in 1839. Her encouragement instigated her husband’s prolific output of orchestral, choral and chamber pieces between 1841 and 1845. Indeed, traces of her own youthful Concerto in A minor occasionally permeate Robert’s first movement, whose coda incorporates a four-note motif from Clara’s third movement. And both concertos’ first movements contain a lengthy slow episode in A flat major bridging the exposition and development sections.

The Intermezzo opens with a coy and playful dialogue between piano and orchestra. Pianist Claudio Arrau asked conductor Colin Davis who was Clara and who was Robert, a quip that nevertheless contains more than a kernel of truth. Husband and wife figuratively merge as one in the passionate central episode in C major, where the cello section’s gorgeous melody is answered by gently decorative piano filigree. Following a return to the Intermezzo’s opening music, Schumann reiterates the first movement’s main theme in the major mode, with soft falling figures from the piano. It leads directly into an exuberant finale, characterised by a wide variety of cross-rhythmic activity, where the soloist has no choice but to channel his or her surface virtuosity towards purely musical values.

Shortly after completing the concerto in mid-July 1845, Schumann suffered a major physical collapse, yet he managed to attend the work’s premiere in Dresden on December 4, with Clara as soloist under the baton of Ferdinand Hiller. Since then, it’s been a repertoire staple in concert and on disc. The 20 pianists I discuss in this survey count among the work’s strongest interpreters on recordings, not to mention many others that readers will undoubtedly criticise me for omitting!

Acoustic and electric

The concerto’s first recording, with pianist Alfred Cortot and Landon Ronald conducting, appeared late in the acoustic era and received an unusually detailed review in these pages exactly 100 years ago (1/1925). Their 1927 electrical recording was superseded by a sonically and musically superior 1934 remake. Cortot’s freewheeling, highly nuanced style makes every note of the solo part count, even his rather melodramatic entry into the third movement. To the general public, however, Myra Hess and the Schumann Concerto were synonymous, as borne out in numerous public performances of it from 1912 until the end of the pianist’s career. Indeed, her 1937 HMV recording was a best seller. Hess’s poetic yet careful pianism is at opposite ends from Cortot’s ecstatic volatility, while Walter Goehr’s pick-up orchestra leaves much to be desired. You hear similar cultivation and caution in Hess’s 1952 remake (also included on the APR set of the pianist’s complete studio recordings), which, however, can boast sonic and orchestral advances, with sympathetic support from Rudolf Schwarz and the Philharmonia Orchestra (3/54).

Alfred Cortot (photo: Bridgeman Images)

The Philharmonia’s formative years are represented by Dinu Lipatti’s 1948 recording with Herbert von Karajan. Considering the tragically short-lived pianist’s iconic status, Lionel Salter’s original negative assessment in these pages (11/48) surprised me. He claimed Lipatti to be ‘out of his element in this work’, treating it ‘too much as a virtuoso’s piece’ and missing ‘the romantic yearning and wistful sentiment which are the very essence of Schumann’. As for Karajan’s contribution, ‘he scarcely bothers to shape the orchestra’s phrases’, while setting ‘some extraordinary tempi’. Rehearing this performance via APR’s most recent restoration, effected from original shellac pressings, I notice more room tone and definition than in previous transfers, with palpable shape, nuance and poise from both soloist and conductor.

Salter also disparaged Claudio Arrau’s 1944 recording with Karl Krueger and the Detroit Symphony (Naxos or Sony, 3/47), while Trevor Harvey waxed ambivalently about the pianist’s 1957 EMI remake with the Philharmonia under Alceo Galliera (EMI/Warner, 5/58). However, Edward Greenfield found Arrau’s 1963 Philips version with the Concertgebouw Orchestra patently inferior to the EMI LP. In the latter, I admire the patient finesse and seriousness with which Arrau unravels the solo part’s thick strands and difficult-to-voice polyphony, despite surprisingly murky mono sonics compared to the far fresher-sounding if musically less interesting 1956 Solomon/Menges/Philharmonia recording (Testament, 7/59, 12/02). Yet Philips’ engineers did better justice to the pianist’s gorgeous and unsplintering sonority, not to mention Christoph von Dohnányi’s firmer, less deferential orchestral support. Arrau’s 1980 Philips remake with Colin Davis and the Boston Symphony (2/82) is no less distinctive, save for an ever-so-slightly less incisive first-movement cadenza.

By contrast, Arrau’s almost exact contemporary Rudolf Serkin would never have won awards for the plushest or most velvet tone. Yet his lean sonority could grip you in the concert hall for its power, projection and definition. More than in his 78rpm-era and mono LP Schumann Concerto recordings with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra, his 1964 stereo version with the same orchestral forces embodies boldness, angularity and sheer swagger in the outer movements. The force and conviction behind Serkin’s accentuation of the finale’s cross-rhythmic phrases and the first movement’s imitative writing represents an ideal blend of head and heart. Yet in the Intermezzo, Serkin shows his genial and expansive side via his conversational responses to Ormandy’s sumptuous orchestral framework, especially when the big C major theme kicks in.

I suspect that RCA Victor withheld releasing Byron Janis’s 1959 recording with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony in deference to Van Cliburn’s imminent version with the same forces. Small wonder that Janis decamped to Mercury, where he would re‑record much of his RCA concerto repertoire and more. Ultimately, Janis’s RCA Schumann appeared on a special fundraising LP and later in RCA’s ‘Point 5’ audiophile LP series. Janis’s handling of inner voices mirrors the sense of tension and release conveyed by his mentor Vladimir Horowitz, as well as the febrile songfulness he brings to lyrical passages. It’s far removed from Cliburn’s easy-going demeanour and appears more in line with Reiner’s no-nonsense precision and sophisticated balances. Similar characteristics define Janis’s Mercury remake, along with the analytic clarity of Wilma Cozart’s signature production values. The Minnesota Orchestra, Stanisπaw Skrowaczewski and the Minnesota Symphony give Janis brilliant support, even if I prefer Chicago’s first-desk soloists over their northern neighbours in these recordings.

Janis’s slightly older American colleague Eugene Istomin was supposed to record the Schumann with Leonard Bernstein, yet his producer John McClure thought an association with Bruno Walter would be better. After hearing Istomin’s recording of Brahms’s Handel Variations, the veteran conductor agreed to record anything the pianist wanted. In an interview, Istomin recalled that Walter was easy to work with, and that the conductor was very happy with the recording, calling it ‘streng aber frei’ (powerful but free). Walter was right. In general, Istomin brings together the best of Janis’s edge-of-seat involvement and Serkin’s rectitude, but with more colour and sustaining power in longer lines.

Wilhelm Backhaus (photo: Bridgeman Images)

Encountering Wilhelm Backhaus’s 1960 recording for the first time while preparing to review the pianist’s ‘Complete Decca Recordings’ box-set (4/20) was a pleasant surprise. Backhaus downplays Schumann’s mercurial mood swings in favour of symphonic continuity, as he builds sonorities from the bottom up. The thick chords never splinter for a second, while rapid passagework, decorative sequences and long trills are firmly etched and decisively shaped. In Backhaus’s hands, the cadenza’s gnarly textures and imitative writing have a Jovian force and kinetic impact that remind me of when Carlos Kleiber described conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in the opening chords of Beethoven’s Coriolan overture as if ‘running into a wall at 60 miles per hour with a Rolls-Royce’. Yet Backhaus is every inch the team player, pulling back when ensemble tuttis or first-desk soloists have centre stage. While Günter Wand obtains palpable linear clarity and across-the-floor discipline from the Vienna Philharmonic, he allows the orchestra’s individual qualities to shine, from the first oboe’s penetrating, slightly acidic tone to the affectionate yet never vulgar string portamentos.

Seventies treasures

The early 1970s brought forth two Schumann/Grieg concerto couplings that critics comfortably recommended for decades. Stephen Kovacevich and Colin Davis evidently rethought and reconsidered Schumann’s score in the manner of an art conservator removing decades worth of dust and grime from a familiar painting. Listen, for example, to the forward-balanced lower woodwinds underneath the oboe’s statement of the first movement’s main theme, the strings’ pinpoint unanimity of attack and release (quite different from Ormandy’s robustness), or the consistent rhythmic alignment between soloist and orchestra in loud tuttis. However, there’s nothing clinical or cold about this interpretation; repeated hearings reveal plenty of inflection points and poetic touches, albeit handled with the utmost subtlety.

Radu Lupu, André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra offer a comparably brisk and straightforward reading, although Decca’s plusher recorded ambience leaves a more generalised and less detailed impression. Considering the (relatively) young Lupu’s penchant for lingering and lily-gilding (for example his indulgent Beethoven Moonlight Sonata), his lyrical bent and boundless colour palette illuminate rather than detract from Schumann’s strong narrative flow. I understand the ‘firm, placid beauty’ to which Richard Osborne referred in his original review, yet disagree with his contention that Lupu’s tone in rapid passages ‘is often warm and “level” to the point of blandness’. That may have been so on LP or cassette back in the day, but emphatically not via Decca’s best CD transfers.

Ivan Moravec (photo: Bridgeman Images)

However, who knew that a truly special, arrestingly individual yet thoroughly stylish Schumann Concerto from the Czech Republic loomed around the corner? Everything about Ivan Moravec’s collaboration with Václav Neumann is special. In the first movement, the uniquely tangy vibrancy of the Czech Philharmonic woodwinds grabs your immediate attention, followed by Moravec establishing the tone with his drop-dead gorgeous entrance. In each movement, Neumann gauges and spaces rubatos and transitions so that they sound both organic and inevitable. And, like Backhaus, Moravec is willing to accompany when the music calls for it, yet he takes proud charge at virtuoso climaxes. Even after nearly half a century, Supraphon’s lifelike sound hasn’t dated one iota.

Into the Digital era

Two antipodal Gramophone reviews typify the polarised critical consensus concerning Krystian Zimerman’s recording with Karajan. ‘Every bar is a voyage of discovery for Zimerman, executed with crystalline tone to match freshness of spirit’, wrote Joan Chissell upon the disc’s first issue. However, Peter Quantrill waxed less sympathetically over DG’s audiophile LP release 35 years later: ‘The orchestra seems not so much to accompany Zimerman … as play along from an adjoining chamber, the better perhaps to paper over interpretative cracks between soloist and conductor’ (1/17). I tend to side with PQ in regard to the piano’s domination in the mix, while Karajan’s forthright and typically blended orchestral framework contrasts with Zimerman’s emphatic assertiveness in the first movement and his slightly square and notey finale.

While the Intermezzo reflects more of a meeting of minds, it’s not quite the playful conversation generated by Murray Perahia and Colin Davis. The latter provides a looser-limbed accompaniment with the Bavarian Radio Symphony than he had with the leaner, more angular BBC ensemble for Kovacevich. There’s more interplay and overall spontaneity between Perahia and Davis in the first two movements compared to the pianist’s Berlin Philharmonic remake with Claudio Abbado (Sony, 1/98). With Abbado, however, Perahia brings more light and shade to the main theme’s dotted notes and allows the cross-rhythms to relax more as they move over the bar lines.

No Schumann Piano Concerto survey can ignore Martha Argerich’s unfettered temperament and total affinity for the composer’s emotional disquiet. The question is: which recording? Her 1978 version with Rostropovich (DG, 11/78) is relatively contained next to the soaring ebb and flow of a live version from the following year with Kazimierz Kord conducting the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra (Accord). They contrast with the stinging wildness of her 1992 remake with Harnoncourt (Warner, 1/95). Her participation in a June 2006 all-Schumann concert with Riccardo Chailly and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, once available on home video, met with deservedly high critical acclaim. She’s no less a firebrand than in the past yet arguably more settled, as borne out by the first two movements’ broader tempos and steadier trajectory. By and large, this is the Argerich Schumann Concerto to have. Decca released an audio-only version in its Decca Concerts download series (1/07) and on physical CD as part of its 2017 ‘The Piano Edition’ 55-disc box-set.

The Portuguese pianist Sequeira Costa’s 1984 recording with the Gulbenkian Orchestra under Stephen Gunzenhauser never seems to emerge from under the radar, although it’s readily available to stream or to download from Naxos. I like the excitement generated by the performers’ animation and urgency, as Costa makes expressive points through the specificity of his phrase-shaping and attentive bass lines. As with the Czech Philharmonic, the Gulbenkian’s winds and brass are prominent in the mix, while strong inner rhythmic momentum compensates for occasionally loose piano/ensemble dovetailing and shaky pickups. Some may feel the Intermezzo to be unduly terse and impatient, yet it leads you forwards as if walking on a bridge between the outer movements. The clarity of Costa’s détaché articulation in the finale helps to characterise his brisk conception, although some of the orchestra’s imprecise chording and raw patches of intonation might have benefited from retakes. Still, I enjoy this interpretation for its freshness and vitality.

Nor should one underestimate Howard Shelley directing from the keyboard on a delightful album that also features the Grieg and Saint-Saëns Second Concertos. I totally concur with Harriet Smith’s enthusiastic endorsement in her original review. Shelley’s outer movements feature unusually fleet basic tempos that allow for natural, meaningful and flawlessly dovetailed rubatos, while the finale’s zest and prismatic transparency have a buoyancy that defies you not to tap your toes in time to the music. While the resonant sound lacks bottom, at least it conveys a semblance of concert-hall realism to which one can easily adjust. This is one of the jewels of Howard Shelley’s prolifically diverse discography.

On original instruments

The HIP movement first broached Schumann’s Piano Concerto on record in 1991 with a Newport Classics release featuring Anthony Newman conducting the New Brandenburg Collegium. If you can find this out-of-print and superbly engineered release, the sensitive and cultivated pianism of Thomas Lorango (1959‑92) is worth the hunt, not to mention the beguiling timbral intimacy of his c1792-vintage Streicher instrument.

Andreas Staier (photo: Bridgeman Images)

Andreas Staier uses a later mid-19th-century Streicher model on his recording with the Orchestre des Champs-Élysées under Philippe Herreweghe. I can understand Rob Cowan’s basic assessment of the performance as more Schubertian or Mendelssohnian than Schumannesque, but he accurately cites distinctive features such as ‘judicious rubato, sensitive phrase-shaping and occasionally arpeggiated chords, with prominent brass, lightly brushed strings and keen interplay between soloist and orchestra’. Yet I find that both the piano soloist’s and conductor’s scrupulous attention to note values and dynamics brings colourful mobility to the outer movements that compensates for whatever lack of gravitas one might perceive. And in the Intermezzo’s big C major melody, the vibrato-less cellos manage to sound refreshingly clear rather than tonally emaciated.

If Staier sometimes struggles to be heard in loudest moments, Alexander Melnikov’s comparably light-sounding 1837 Érard bristles more judiciously in tandem with Pablo Heras-Casado and his Freiburger Barockorchester. Their first movement succeeds best. Melnikov is one of the few soloists to launch into the opening flourish in strict tempo, not yielding one millimetre. From that point on, the pianist and conductor pursue a more affettuoso agenda than Staier/Herreweghe, as they stretch transitional passages to their limits, tapering phrases and uncovering inner voices that may well have surprised the composer himself. In addition, the dry, biting quality of Melnikov’s Érard gives rapid accompanimental passages uncommon clarity. But their perfunctory Intermezzo hardly hints at Schumann’s grazioso directive. In his original review, David Threasher acknowledged the finale’s uncommonly moderate tempo as potentially controversial. ‘However, when played, as here, with Melnikov’s imagination, the effect is not only to reveal the ingenious construction and orchestration of the work but also – given the swing that he and Heras-Casado impart to it – to show how closely it is related to the galumphing polonaise that closes the Violin Concerto’. I find their foursquare reading joyless and enervated, and anything but a bona fide Allegro vivace. Watch the movement on Harmonia Mundi’s supplementary DVD, and you’ll notice Melnikov and Heras-Casado grimacing as if they were in pain.

Finally, for period style on modern instruments, Warner Classics’ recent release with Beatrice Rana and Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducting the Chamber Orchestra of Europe mirrors the best aspects of the Lorango, Staier and Melnikov versions in regard to balances and pacing. ‘Rana’s indulgent tempo-bending (just listen to the opening of the cadenza) and her tendency to lean heavily into the peaks of phrases may strike some listeners as bordering on the fussy’, wrote my colleague Peter J Rabinowitz, whom I also thank for his kind words about my booklet notes for this disc. However, one person’s fussy is another person’s astute or inspired, and I cannot disparage Rana’s inherent musicality.

As you’ve gathered, those seeking a Schumann Piano Concerto recording are spoiled for choice, and I would not want to be without most of the versions cited in my overview. However, the Supraphon recording with Ivan Moravec, Václav Neumann and the Czech Philharmonic reigns at the top of my list for its ideal fusion of technical finish, insightful musicianship, imaginative profile and sonic splendour.

The Top Choice

Ivan Moravec; Czech PO / Václav Neumann (Supraphon)

This classic interpretation has everything one could wish for: a pianist of immeasurable refinement and class, one of the world’s most characterful orchestras, a congenial yet strong conductor and gorgeous engineering.

The Period Choice

Andreas Staier; Orch des Champs-Élysées / Philippe Herreweghe (Harmonia Mundi)

There’s more beneath the surface of Staier and Herreweghe’s slender dimensions than one would suspect, so don’t dismiss this recording out of hand as mere ‘Schumann lite’.

The Underrated Choice

Wilhelm Backhaus; VPO / Günter Wand (Decca)

The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra provide a genial foil to Wilhelm Backhaus’s grounded sobriety, resulting in a stimulating collaboration that proves the old adage ‘opposites attract’.

The Historic Choice

Alfred Cortot; orch / Landon Ronald (Naxos)

Alfred Cortot’s re-creative genius and full immersion into Schumann’s style and spirit results in a performance that remains ecstatically alive, especially in this 1934 recording, the best of Cortot’s three.

Selected discography

Recording Date / Artists / Record company (review date)

1934 - Alfred Cortot; LPO / Landon Ronald Naxos 8 110612; Warner Classics (40 CDs) 5419 74719-4 (9/23)

1937 - Myra Hess; orch / Walter Goehr Naxos 8 110604 (12/37, 5/01); APR APR7504 (5/13)

1948 - Dinu Lipatti; Philh Orch / Herbert von Karajan APR APR6032 (11/48, 10/20)

1959 - Byron Janis; Chicago SO / Fritz Reiner RCA 88843 09175-2; 88985 31330-2

1960 - Wilhelm Backhaus; VPO / Günter Wand Decca (39 CDs) 483 4952 (7/60, 1/63, 4/20)

1960 - Eugene Istomin; Columbia SO / Bruno Walter Sony Classical MK42024 (9/86); 88875 02617-2 (2/16)

1963 - Claudio Arrau; Concertgebouw Orch / Christoph von Dohnányi Philips 432 229-2 (9/64)

1964 - Rudolf Serkin; Philadelphia Orch / Eugene Ormandy Sony Classical MYK37256 (8/65)

1970 - Stephen Kovacevich; BBC SO / Colin Davis Decca 464 702-2PM (3/72)

1973 - Radu Lupu; LSO / André Previn Decca 414 432-2DH (2/74, 5/85); 466 383-2DM

1976 - Ivan Moravec; Czech PO / Václav Neumann Supraphon SU3508-2 (10/78, 3/01)

1981 - Krystian Zimerman; BPO / Herbert von Karajan DG 439 015-2GHS (5/82, 10/84)

1984 - Sequeira Costa; Gulbenkian Orch / Stephen Gunzenhauser Marco Polo 8 220306; Naxos 8 550277

1987 - Murray Perahia; Bavarian RSO / Colin Davis Sony Classical 88697 72100-2 (5/89)

1995 - Andreas Staier; Orch des Champs-Élysées / Philippe Herreweghe Harmonia Mundi HMA195 1731 (9/96)

2006 - Martha Argerich; Leipzig Gewandhaus Orch / Riccardo Chailly Decca (55 CDs) 483 2243DX55; EuroArts 205 5498 (7/07)

2008 - Howard Shelley; Orch of Opera North Chandos CHAN10509 (5/09)

2014 - Alexander Melnikov; Freiburg Baroque Orch / Pablo Heras-Casado Harmonia Mundi HMC90 2198 (9/15)

2022 - Beatrice Rana; COE / Yannick Nézet-Séguin Warner Classics 5419 72962-5 (3/23)