The Ill-Tempered Clavier: The Unspoken Taboo of Criticizing Classical Music’s Sacred Names

Charivari

Friday, March 7, 2025

Charivari has had enough of pretending to like things he doesn’t, including composers whose music is considered by some to be beyond criticism or the vagaries of personal taste

Do you dislike the music of certain composers but are afraid to admit it? I have many knowledgeable and musically literate friends who do, but cannot, for professional reasons, divulge their opinions for fear of being pilloried, much as they would not admit to being a Brexiteer in a room full of Remainers, or wear a Rangers scarf in the Celtic stands.

If they do put on a tin hat and venture a peek over the trench top, they risk being shot down as an uneducated oaf, beyond the pale and not worth conversing with. You see, those involved in the creative arts are overwhelmingly of a left-leaning persuasion, and I have noticed over the years that people on the left tend to be less generally accepting of the views of right-leaning friends than the other way around. I don’t know why that should be, but it is so: the left seem to be less tolerant of opinions (including political and musical) with which they disagree than those right-of-centre.

This came home forcibly last week when I was chatting to a distinguished (left-leaning) opera director whose company I’ve enjoyed for many years. We were discussing the merits of Elektra (the Richard Strauss opera), which he was going to see at Covent Garden. He was raving about what a great work it was. I disagreed. I said I thought it was one of the ugliest of 20th-century operas and not a great night out. He countered by saying it was a great work that opened the door to the rest of 20th-century opera. There I agreed. That is exactly what I have against it, I said. It helped kill off the genre as a popular entertainment. Well, said my opera friend, in that case I have just four words for you. Oh yes? I asked. And what are they? He then instructed me to go forth and multiply. End of discussion. All further views shut down. There could be no other acceptable opinion on the merits of Elektra than his.

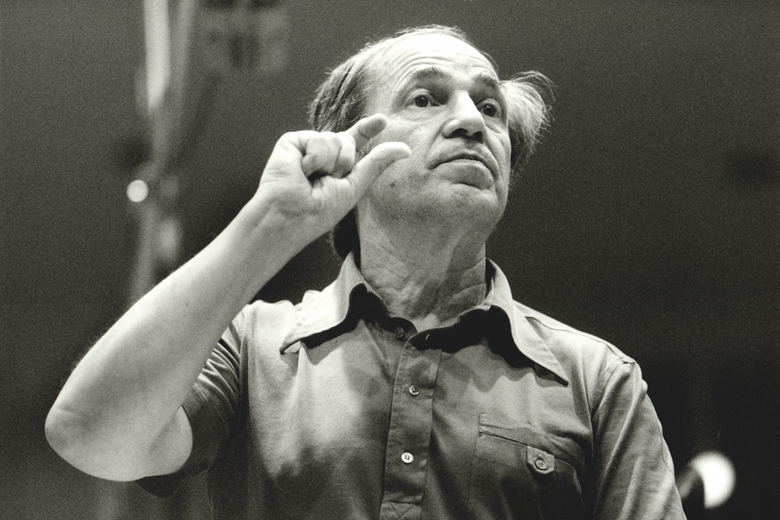

And then there was the Christmas party when one of my esteemed colleagues was holding forth on the merits of Boulez’s Second Piano Sonata and the genius of Boulez in general. Readers of this column will not be unfamiliar with my views on the late iconoclast. Not an aural experimenter of the Stockhausen and Cage ilk but a fiercely intellectual avant-garde thinker who, in his younger days, announced that he would like to see all the opera houses in the world burned down. He despised the likes of Puccini and Rachmaninov, mainly, I think, because they had the effrontery to write melodic, accessible music that entertained the hoi polloi. Boulez seemed convinced that his own music was not only better but more important, even though it became abundantly clear even in his lifetime that very few people enjoyed playing it and even fewer enjoyed listening to it. But criticise Boulez at your peril. When I said that for me an hour spent with Boulez is an hour wasted, the look of disbelief and astonishment on the face of my esteemed colleague was like something out of a Bateman cartoon: ‘The Man Who Said He Hated Boulez!’

A German friend who shares my view reminded me that there is a concert hall in Berlin called the Pierre Boulez Saal. ‘Very few people know his music – very little of it is ever heard there – but,’ he advises me, ‘do not to fall into this trap. Hold back diplomatically, otherwise you will be treated with hostility or not taken seriously. Even musicians, professors and others don’t dare to express their true opinions.’

This is a microcosm of the wider world today where people feel unable to speak on controversial (and much thornier) issues for fear of being shouted down, cancelled or losing their jobs. From whence came this aggression? Instead of a pleasant or even heated exchange of opposing views that end with a slap on the back and mutual respect, there is dismissal, bad blood, and the keyboard warriors of social media, seen nowhere more clearly and depressingly than on the campuses of our universities with their over-sensitive, easily-offended inhabitants.

With this in mind, whether artist, composer, promoter, broadcaster or critic, you will rarely find anyone making their living in the world of classical music who would dare voice any criticism of any of my personal sextet of hallowed names, six composers whose music just doesn’t appeal to me, six untouchables whose names all happen to start with B: Bruckner, Berg, Britten, Birtwistle, Busoni (whose centenary went by virtually unnoticed, with the notable exception of International Piano) and, primus inter pares, Boulez, whose centenary the BBC will no doubt be pushing down our throats this year. IP

This feature originally appeared in the SPRING 2025 issue of International Piano