A Pianist’s Nibelung’s Hoard: Inside the Rediscovered Liszt-Stradal Collection

Kenneth Hamilton

Friday, March 7, 2025

Kenneth Hamilton describes the exciting discovery of a precious collection of Liszt materials in a small museum in the Czech Republic, part of the legacy of Liszt’s pupil August Stradal

The previous instalment of this column was announced as the first of two parts outlining Chopin’s teaching practices, so readers may quite rightly be expecting this issue to contain the second part. Indeed, this is what I myself expected. But I have something so exciting to share that the second part of ‘Chopin as teacher’ has been put on hold temporarily, and will follow in the next issue. Please read on for something completely different.

Some years ago, I came across the following lines in a book called Erinnerungen an Franz Liszt (‘Memories of Franz Liszt’) by his student August Stradal:

'Liszt gave freely of his time to those he was convinced understood him and sensed his greatness. He untiringly and enthusiastically made corrections, demonstrated certain passages, and made many annotations in the scores of the student he was working with. I consequently possess a thick volume of Liszt pieces into which the master wrote many comments for me – truly a priceless "Nibelung’s hoard".'

Stradal isn’t a household name these days, although in his lifetime he was fairly well known as a performer, a minor composer and a prolific arranger for piano. He not only transcribed numerous orchestral works by his teachers, Franz Liszt and Anton Bruckner, but also a vast range of music from the Baroque era onwards, including pieces by Buxtehude, Frescobaldi and Purcell – composers rarely encountered in Romantic piano transcriptions. Some readers may have heard Víkingur Ólafsson’s fine, meditative recording of the Bach/Stradal Andante from the Organ Sonata No 4, or Risto-Matti Marin’s admirable discs of the complete Liszt/Stradal Symphonic Poems.

Stradal was born in 1860 in Teplice in Bohemia. He died in 1930 in what was then Schönlinde and is now Krásná Lípa. At the time of his birth, the area was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and predominantly German-speaking; by the time of his death, it was part of Czechoslovakia. It is now in the Czech Republic. The political vicissitudes of the region (similar to Liszt’s own ‘borderland’ birthplace of Raiding) significantly hindered Stradal’s career after the First World War and had even more serious consequences for his Viennese-born wife Hildegard (1864-1948). She was expelled from Krásná Lípa after the Second World War, along with others of German/Austrian origin, and ended her days in an old folks’ home in Halle in Saxony-Anhalt. Hildegard was herself a professional singer and writer, with several collections of poetry to her name. She published a touching biography of her husband, August Stradal: Ein Lebensbild, in 1934. And (as we shall see below) she was evidently no passive partner in respect of the writings attributed to her husband.

Stradal had briefly been a pupil of Theodor Leschetizky before coming under Liszt’s spell in late 1884. ‘The master’ quickly assumed a quasi-paternal role in his life – Stradal had lost his own father while still a child. He became not only a student, but an especially trusted one, who acted as an amanuensis and travel companion. In gratitude, Liszt dedicated the delicately contemplative nocturne En rêve (Dreaming) to him in 1885. Stradal was a member of that close coterie of outstanding Liszt students (Arthur Friedheim, Alexander Siloti, Bernhard Stavenhagen and August Göllerich were some of the others) who saw the master on a virtually daily basis during his last years. This was a distinctly different relationship from that experienced by the ephemeral hordes of students who congregated around Liszt during his famous masterclasses. Many of these were ‘a pitiful crowd of sycophants and incompetents’, as the conductor Walter Damrosch memorably put it. Genuinely talented students, on the other hand, not only performed at the masterclasses, but were also given private lessons. ‘Those who had the right to desire explicit information’, Arthur Friedheim reminisced, ‘could always have Liszt explain the intricacies and subtleties of pedalling, and even get him to suggest useful fingerings.’

August Stradal, then, was one of the favoured few. When, some time ago, I was writing a book chapter entitled ‘Liszt’s long-ignored legacy to his students’, I wondered whether Stradal’s ‘Nibelung’s hoard’ of scores annotated by the master could possibly have survived, and if so, where on earth it was. I knew that Stradal had died in Krásná Lípa, and I knew that the town museum in Rumburk, around four miles away, had Stradal’s clavichord on display, but there was no sign of his score collection – until now.

I was recently chatting to a friend and colleague, the Liszt scholar Nicolas Dufetel, during a conference at the Liszt Memorial Museum in Budapest. ‘The Stradal collection’, he said, ‘it’s in the Rumburk Museum’. ‘I thought they only had his clavichord’, I replied. ‘No – in the storerooms they have a host of scores and manuscripts! I saw them and took a few photos. But they’ve never been properly catalogued – no one knows exactly what’s there.’

So in December I flew from Frankfurt to Dresden, travelled the picturesque train line from Dresden to Bad Schandau, and changed there to a train heading to the little town of Rumburk in the Czech Republic. Over the next two days, I examined the entire Stradal collection with the kind and generous help of Assistant Curator Lucie Zamrzlová and her welcoming colleagues. The Museum (muzeumrumburk.cz/en) has a small but fascinating exhibition of Stradal’s Liszt memorabilia: Liszt’s top hat, his conductor’s baton, even a slightly macabre casket with a thick lock of his hair. And yes – Stradal’s clavichord is there too.

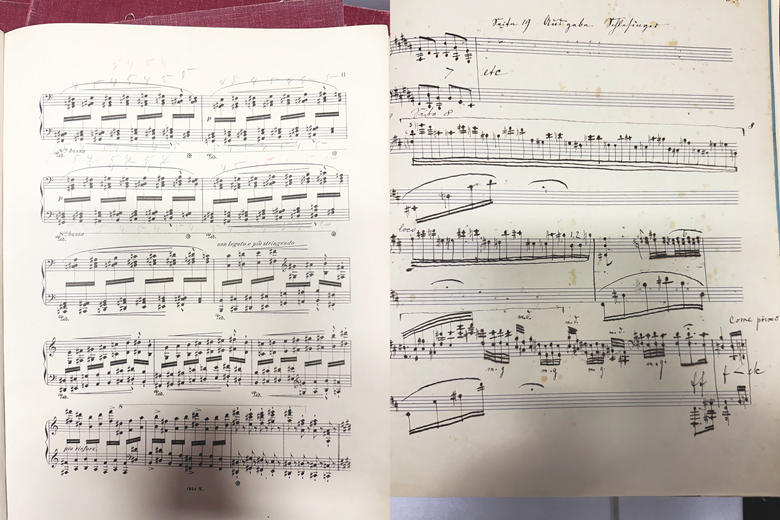

But the real treasure lies behind the scenes: scores of Funérailles, of St Francis of Paola walking on the waves, of the Second Piano Concerto and other pieces, with pedallings, fingerings and rewritings that do indeed look as if they have been inserted by Liszt himself. There’s also a manuscript in Stradal’s hand of Liszt’s late revisions to Réminiscences de Robert le Diable (subsequently published in Lina Ramann’s Liszt-Pädagogium); a manuscript in the hand of August Göllerich of Liszt’s cadenza to his transcription of Schubert’s ‘Leise flehen meine Lieder’ (written out by Göllerich as a wedding present to August and Hildegard Stradal in 1888); numerous Liszt first editions; and many manuscripts of Stradal’s own arrangements, including several that remain unpublished. And finally, there is the manuscript of a vast, also unpublished, five-volume book on Liszt’s works (not to be confused with the much shorter Franz Liszts Werke – besprochen von August Stradal, which appeared in 1904). Some of this manuscript is in August’s hand, much of it in Hildegard’s. She writes in the preface that she ‘prepared the manuscript for printing’ after her husband’s death, but she obviously did a lot more than that.

It’ll take time fully to digest this material, but perusing it was utterly fascinating. Turning the pages of the collection, I felt an uncannily close connection to Liszt and his students, as if I had been taken back to the 1880s. I recently recorded the revised version of Réminiscences de Robert le Diable for Volume 3 of my Liszt series, which will be released later this year, but there’s more work to be done. The Stradal/Liszt collection belongs artistically not only to Rumburk Museum, but to the entire musical world. ‘Truly a priceless Nibelung’s hoard’. IP

This feature originally appeared in the SPRING 2025 issue of International Piano