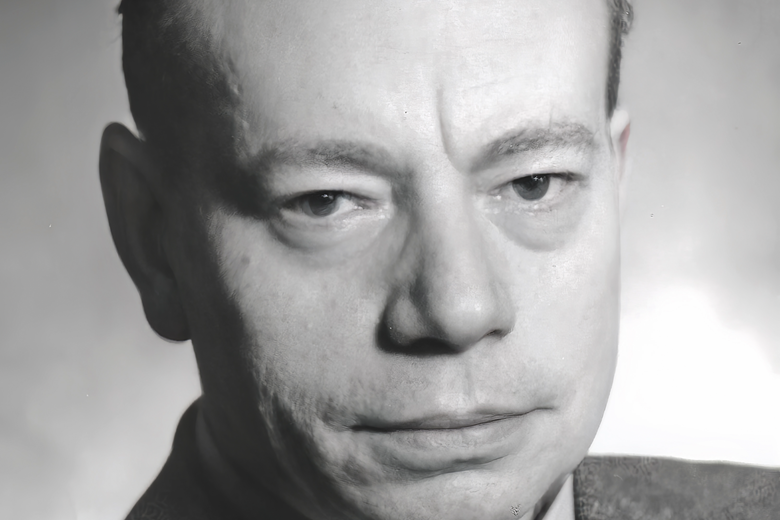

Victor Schiøler: The Forgotten Danish Virtuoso

Mark Ainley

Friday, March 7, 2025

Mark Ainley celebrates the exalted artistry of the Danish pianist Victor Schiøler, whose posthumous reputation lapsed – at least outside his own country – until the Danish label Danacord helped to reintroduce this great pianist to a wider public

Register now to continue reading

This article is from International Piano. Register today to enjoy our dedicated coverage of the piano world, including:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to International Piano's news pages

- Monthly newsletter