Three pioneers of film music: Shostakovich, Korngold and Copland

Andrew Farach-Colton

Tuesday, October 11, 2022

Among the many concert hall composers seduced by cinema were Shostakovich, Korngold and Copland. Yet each brought an individual outlook and had very different experiences, relates Andrew Farach-Colton

‘It’s time to take cinema music in hand, to eliminate the bungling and the inartistic and to thoroughly clean the Augean stable. The only way to do this is to write special music’

Dmitri Shostakovich declared the words above in an article published in advance of the premiere of the silent picture New Babylon in March 1929. It was his first full-length film score and he was 23.

The young composer was already something of an industry veteran, however, for in order to help his family make ends meet, he’d spent a considerable portion of his later teenage years accompanying silent films on the piano in several of St Petersburg’s larger movie palaces (it was only following the spectacular success of his First Symphony in 1926 that he was able to quit that line of work, which he found gruelling and repetitive).

In tandem with New Babylon’s directors Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg – founders of an experimental theatre group known as the Factory of the Eccentric Actor – Shostakovich boldly forged a new relationship between sound and image. ‘In those years,’ according to Kozintsev, ‘film music was used to strengthen the emotions of reality, or, to use current terminology, to illustrate the frame. We immediately came to an agreement with the composer that the music would be linked to the inner meaning and not to the external action.’

Perhaps because of the many years he’d spent working in the cinema as an accompanist, Shostakovich had a clear and immediate sense of music’s potential to function not merely as a narrative accessory but as a powerful tool to express psychological, spiritual or even philosophical signs and subtleties. ‘For example,’ the composer explained, ‘at the end of the second reel the important episode is the German cavalry’s advance on Paris, though the scene ends in an empty restaurant. Silence. But, in spite of the fact that the cavalry is no longer on screen, the music continues to remind the audience of the approaching threat.’

From the start, too, Shostakovich conceived of the film score as a cohesive entity rather than a patchwork quilt of cues, describing his music for New Babylon as maintaining an ‘unbroken symphonic tone throughout’. And, though he employs a broad stylistic coalition that includes raucous polkas, inebriated waltzes, acerbic quotations (most notably, from ‘La Marseillaise’) and bleak cantilenas, one marvels at the score’s coherence. To my ears, at least, New Bablyon’s easy eclecticism looks forward to some of Shostakovich’s more enigmatic masterworks, including the Sixth, Ninth and Fifteenth symphonies.

New Babylon was a total flop. The film’s expressionist imagery puzzled audiences, cinema orchestras struggled with the complicated music, and the synchronisation problems were nightmarish, given the unreliability of the technology. Yet Shostakovich appears to have been unfazed, and continued experimenting and pushing boundaries in this new genre as the era of the silent film ended and the soundtrack was born.

There are spectacular moments in Alone (1931), including the scene at the end of the first reel, where an ethereal, Italianate chorus of crockery begs the heroine to stay in Leningrad. The Golden Mountains (1931) features an imposing fugue for organ and orchestra (unfortunately cut from the final version of the film). Shostakovich’s inventiveness was simultaneously aided by improvements in sound quality and hampered by politics, as Stalin tightened his grip on the Soviet cinema. Following the composer’s fall from the government’s grace in 1936, writing music for films became a matter of survival, while experimentation was to be studiously avoided. Little music from this period is from Shostakovich’s top drawer. There are exceptions, however, like the charming, rather Mahlerian score he provided for the cartoon The Tale of a Silly Little Mouse (1940).

It would be a decade after Stalin’s death before Shostakovich returned to the world of the cinema with real enthusiasm, providing music for a pair of Shakespearean films by his old friend Kozintsev: Hamlet (1964), composed soon after the Thirteenth Symphony; and King Lear (1971), written hard on the heels of the Fourteenth. Both scores are typical of the composer’s late style in their emotional starkness and structural concision, and are perfectly in tune with Koznitsev’s grimly granitic imagery. And, last but not least: Sofia Perovskaya (1968), produced to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Revolution, is far from Shakespeare, though it, too, inspired what’s arguably Shostakovich’s most hauntingly atmospheric, profoundly eloquent film score.

Korngold

For Erich Wolfgang Korngold, scoring films would also become a matter of survival. The son of Vienna’s most powerful music critic, Korngold was a wunderkind of Mozartian proportions. Mahler heard a cantata by the 10-year-old composer and declared the boy a genius; soon thereafter, Richard Strauss had a similar reaction. At 13, his ballet-pantomime Der Schneemann was produced at the Vienna Court Opera, and by the time he was in his early twenties, Korngold’s works were in demand across Europe and in the United States.

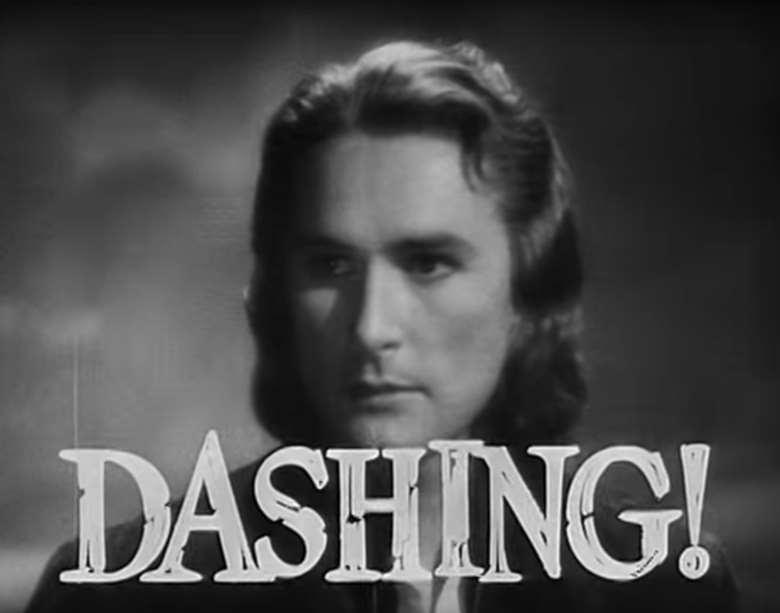

Korngold’s first foray into film came in 1934 at the behest of fellow Austrian Max Reinhardt, who was in Hollywood to direct A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The composer quickly proved himself to be a natural at dealing with the myriad complications of film production, and was immediately invited back for other projects, including his first original score, Captain Blood (1935), starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland.

Although he had just three weeks to complete Captain Blood, the epic, swashbuckling character of the score wowed Hollywood insiders and moviegoers alike. Brendan G Carroll, Korngold’s biographer, writes: ‘Film music more or less came of age with Korngold, who in this one film showed what could really be achieved with a symphonic score…His music was designed to elevate the sometimes cardboard events on the screen and to flesh out the romantic dream that he instinctively recognised as underlying the story.’ Recognition came swiftly. The following year, his score for Anthony Adverse (1936) won an Oscar. Despite his instant celebrity, Korngold felt out of place in Los Angeles and longed to remain in Vienna. But the Anschluss of 1938 left the composer and his family, who were Jewish, no choice but to make a new home in California. It wasn’t such a terrible proposition, really. Korngold’s worth was recognised by the studio moguls, and his contract was the most generous and flexible in the business. At first, Korngold seemed genuinely excited by the medium, too, telling an interviewer, ‘music is music whether it is for the stage, rostrum or cinema’. Not only that, he also saw an opportunity to educate. ‘Fine symphonic scores for motion pictures cannot help but influence mass acceptance of finer music,’ he said. ‘The cinema is a direct avenue to the ears and hearts of the great public.’

Korngold pulled out yet another Oscar-winner: The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), whose heady mix of pomp, passion and playfulness is surely worthy of Strauss. Not surprisingly, given the superlative quality of the film as a whole, Robin Hood is widely regarded as one of Korngold’s finest creations, alongside The Sea Hawk (1940) and Kings Row (1941). Yet there are other lesser-known works of equal stature. The Sea Wolf (1941), for instance, is the composer’s darkest and most modern-sounding score. It’s also one of his most coherent. With an unrelentingly tense, fog-shrouded atmosphere, it plays like a tone-poem and makes gripping listening from first note to last.

But, as always in Hollywood, fashions come and go. After the war, Korngold was no longer being offered top-grade films. He nurtured hopes of returning to Europe and re-establishing his position in the world of opera and concert music. Now, however, he was branded as a movie composer (and a passé one, at that), and thus not to be taken seriously. Korngold’s sublimely lyrical Violin Concerto was written off by critics as ‘a Hollywood concerto’, and described snidely as ‘more corn than gold’. And his superbly wrought Symphony (1952) received only one performance before his death in 1957.

Copland

Aaron Copland wrote all but one of his film scores between 1939 and 1948 – Korngold’s heyday in Hollywood, which may partially explain his outburst in a 1940 article. ‘Most scores, as everybody knows, are written in the late-19th-century symphonic style…But why need movie music be symphonic? And why, oh why, the 19th century? Should the rich harmonies of Tchaikovsky, Franck and Strauss be spread over every story type, regardless of time, place, or treatment?’ Copland’s answer is obvious, and he’d already proven himself able to strike out in a new direction with his music for The City, a documentary featured prominently at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. In its best moments, The City serves as something of an urban counterpart to Billy the Kid, Copland’s choreographic evocation of the Wild West, composed just a year earlier.

In 1939 Copland published his book What to Listen For in Music, including in it a chapter on film music. ‘Film music constitutes a new musical medium that exerts a fascination of its own,’ he begins. ‘Actually, it is a new form of dramatic music – related to opera, ballet, incidental theatre music – in contradistinction to concert music of the symphonic or chamber-music kind.’

Film music clearly exerted a fascination for Copland; he’d been angling for a gig in Hollywood for several years. The success of The City gave him entrée at last, and his first assignment was an adaptation of John Steinbeck’s novella Of Mice and Men. Copland composed no more than a dozen brief cues for the film, using silence to build dramatic tension. Such sparing use of music was in stark contrast to the quasi-operatic musical flow that was current in Hollywood at the time. The industry took notice, however, and Copland was nominated for two Oscars.

Copland was not Thornton Wilder’s first pick to score the movie version of his Broadway play Our Town (the playwright had hoped to employ Virgil Thomson or George Antheil). Copland eventually prevailed, of course, and it was a wise choice, for his quiet, restrained score (1940) fits this small-town drama to perfection. Again, Copland was nominated for a pair of Academy Awards.

His next Hollywood adventure came in 1943, when he worked on The North Star, a film designed to inspire pro-Soviet feelings in the aftermath of Hitler’s invasion of the USSR. Needless to say, given the timing, the result was controversial, and the music quickly got lost in the shuffle (though it did earn the composer yet another Oscar nomination). Listening today, the score seems uncharacteristically diffuse. There are some striking moments, though, including ‘Guerillas Return’, which bears an intriguing resemblance to some of Shostakovich’s cinematic battle scenes. The Cummington Story (1945), a government-sponsored propaganda film about some Eastern European refugees living in a small Massachusetts town, was far more successful, both musically and politically. And Copland thought enough of the score’s worth that he recycled numerous sections of it in later years.

Controversy over The North Star or no, Copland was still admired by many in Hollywood, and he returned in 1948 for his second Steinbeck-based project: The Red Pony. This time, though, he eschewed Of Mice and Men’s economy of utterance and composed cues generously, producing a good hour’s worth of music. The film’s rural setting (a California ranch) is quintessentially American, and the music is (in its orchestral suite, at least) a worthy companion to Copland’s more famous ballets.

That same year, Copland scored The Heiress (an adaptation of Henry James’s novel Washington Square). This was the most traditional story he had tackled thus far, with its historical setting (New York in the 1850s) and overt love story. To some ears, Copland’s response may sound uncharacteristically lush. Yet, while it’s true that the violins seem to be the prime movers, tune-wise, I’d argue that it’s the yearning quality of the melodies themselves – abetted by gently aching harmonies – that gives the score its exceptional richness.

After The Heiress, Copland left Hollywood for good, finally taking with him an Academy Award. Eight years earlier, he had written: ‘What screen music badly needs is more differentiation, more feeling for the exact quality of each picture.’ In some half-dozen scores, he’d shown precisely how this could be done.

This article originally appeared in the April 2011 issue of Gramophone magazine. To find out more about subscribing, visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe