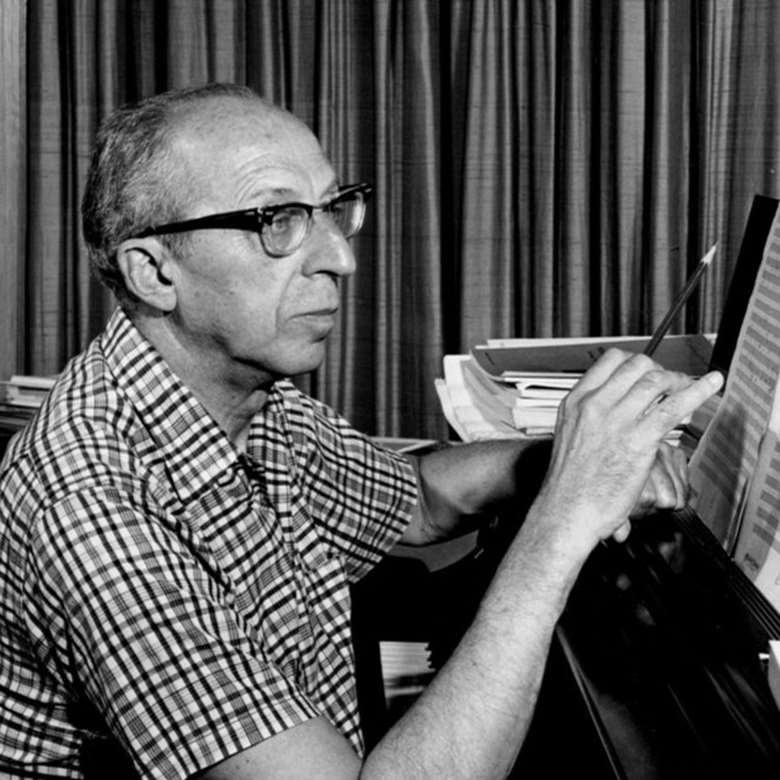

Classic Aaron Copland interview: "I'd just like to get up there and tell them how my music should go"

Gramophone

Thursday, March 24, 2016

Andrew Keener spoke to the American composer on the occasion of his 80th birthday in the February 1980 issue of Gramophone

"Not too peaceful, clarinets...violins, that 32nd note should be louder." Two characteristically straightforward requests from Aaron Copland during a rehearsal for his 80th-birthday concert with the London Symphony Orchestra last December. The remarks, spoken over the music, offer a fair indication of the unaffected rostrum manner of this distinguished composer/conductor (more than once I was put in mind of Percy Grainger's "louden lots", and similar entreaties to his performers). The beat is concise and alertly inflected at the outermost points, amounting almost to a ricochet on the second and third measures of a moderate 4/4 – unmistakably the beat of one on whom jazz once exercised a vital influence. I can remember few more electrifying performances of Walton's Portsmouth Point Overture than one which Copland gave in London several years ago. That so familiar a figure on the rostrum (the CBS catalogue currently represents him as conductor of over 20 of his works) should have come relatively late to conducting is partially explained, in Copland's own words, by the advice he once received from a much senior friend. "It is very important as you get older," she had told him, "to engage in an activity that you didn't engage in when you were young, so that you are not continually in competition with yourself as a young man." The conductor's baton, writes Copland (The New Music 1900-60: Macdonald 1968), "was my answer to that problem". At 80, he is a measured, easy-going conversationalist, the voice seeming even more youthful, the manner somehow even clearer and more relaxed when heard reproduced by a tape recorder several hours later.

Copland traces his discovery of conducting to an appearance with the Mexican Symphony Orchestra in 1947. "Eventually you feel, 'I'd just like to get up there and tell them how my music should go' – even if you know that the fellow up there, if he's Bernstein, for instance, can do it much better than you!" His approach to the rostrum appears to have been remarkably similar to his musical awakening in childhood and early adolescence in Brooklyn. "Music," he writes (The New Music 1900-60), "was a discovery I made all by myself." How, I wondered during our conversation an hour or two before the concert, did the early stages of this discovery come about? "Well, I was the youngest of five, and I used to listen to my brother and sister playing violin and piano. His big number was the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto – though he never played it in public! – and it was my job just to sit and listen. Then my sister gave me my first piano lessons...after a while, she said, 'I can't teach you any more, you'll have to get a real teacher.' So I told my father this and he said, 'Oh, we've wasted so much money on the older children, and we don't want to waste any more! ' But I talked him into it, and in the end it was a great surprise when I told him I wanted to become a composer of so-called 'classical' music. 'Where d'you get such an idea?' he asked. Where did I? I don't know. To start with I suppose it was just inborn love of music." The simplicity of manner here eludes capture in print.

Aaron Copland's distinction as one of Nadia Boulanger's first composition pupils in Paris is as widely reported as his prompt response to an advertisement in the musical press during the winter of 1920. In six months, read the announcement, a new music school was to be established in the Palace at Fontainebleau. As Copland is quick to point out, the two pieces of information have tended to become misleadingly telescoped. "It says in the books that I went to Paris to study with Boulanger, which is an absolute fiction. I couldn't possibly have heard of Nadia Boulanger in Brooklyn – but once such a thing gets printed...well, people say it's in a book, so it must be true! And you never catch up with it." Copland's apprehension towards the permanence of the written word is frequently apparent in his own essays: "The preceding paragraph proves how dangerous it is to attempt to predict the course that any current musical development will take," he writes with characteristic honesty in a 1967 note at the foot of his essay New Music in the USA, first published some 25 years previously.

While Copland admits to having uncovered much standard repertoire for himself ("During these formative years...some instinct seemed to lead me logically from Chopin's waltzes to Haydn's sonatinas to Beethoven's sonatas to Wagner's operas"), there was no shortage of fundamental musical tuition during his late teens. "I was put through harmony and counterpoint by Rubin Goldmark, a nephew of Karl Goldmark. So when I went to Paris I wasn't looking for a teacher of the mechanics of music, but for someone who knew what was going on. Boulanger did have a very inflexible side, but she was very open-minded with me, and took what I can best describe as a general attitude of approval. That was perhaps most valuable of all."

Such was Boulanger's 'approval', that with the announcement of Koussevitzky's Boston appointment in 1924, she announced to the young composer that "We must go to Boston! – there were no two ways about it. So we went and visited Koussevitzky, and by the time the visit was over, he said to me, 'You will write an organ symphony, and Mlle Boulanger will come and play the organ part with me in Boston!' I couldn't believe my ears!" Months later, fearing perhaps, that the conservative New York audience would not be able to believe theirs when faced with such asperity as that of the Symphony, the conductor Walter Damrosch announced, "If a young man at the age of 23 can write a symphony like that, in five years he will be ready to commit murder." Luckily, writes Copland, his prophecy came to nothing.

Aaron Copland's spell in Paris also brought him into contact with the Spanish pianist Ricardo Viñes – one of a surprising number of non-French pianists who were distinguishing themselves in French music. "He used to play modern repertoire, and I thought he'd teach me how to play Debussy and Ravel, Falla, that sort of thing." Confidingly: "But I don't remember learning much from him. He never said very much – he'd shake his head...say goodbye!' Copland chuckles. Rather like his earliest musical awakening, one suspects that his style and development as a pianist have largely come from within. That his playing possesses the unmistakably idiomatic feeling of his popular works of the thirties and forties can be heard from his own recording of the Piano Concerto with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. The work is described by Copland as "the last of my experiments with symphonic jazz", in which he had taken the "limited scope" of the idiom as far as he felt able.

Between this Concerto and the well-known orchestral compositions came a group of altogether more astringent works, some of them of an almost Webernian economy. They include a piece for string quartet, Vitebsk, for piano trio (based on a Jewish theme), and the Variations for piano, which Copland describes as "still comparatively difficult to perform and difficult for an audience to comprehend". That these works – and a group of equally uncompromising more recent ones including Inscape (1967) - should have come from the same creative intellect as El Salon Mexico has prompted many commentators to write of a dichotomy between Copland's 'serious' and 'popular' works. The composer himself regards such a "split down the middle" as something not to be encouraged: "I prefer to think that I write my music from a single vision; when the results differ it is because I take into account with each new piece the purpose for which it is intended and the nature of the musical materials with which I begin to work." His 12-note works, such as the Piano Variations, Copland now regards as "just a different way of thinking about a combination of notes, a stimulus to thought which wouldn't have come in the ordinary way". Characteristically, he is loath to describe the tone row, or any other compositional technique, as dead, insisting that It is the individual composer's ingenuity and imagination which decides the life or death of a style, not the length of time for which a technique has been explored.

No doubt it is Copland's concern for the "purpose for which each new piece is intended" which helped to ensure his success with film music. Among the most distinguished are his scores for Of Mice and Men and Our Town, which date from the 1940s. Some of the film music written for Samuel Goldwyn was conceived, late at night, at the director's Hollywood studios. It was an ideal atmosphere in which to compose: "An air of mystery hovers over a film studio after dark. Its silent and empty streets give off something of the atmosphere of a walled medieval town; no one gets in or out without passing muster with the guards at the gate" (The New Music 1900-60). When, I wondered, did Copland first work with Goldwyn? "For Goldwyn! Nobody worked with him!...I began in the forties. He was the big shot in an office. You weren't often called up there...He didn't know much about music!" - this said as a kind of rueful aside, accompanied by a conspiratorial lowering of voice: "I remember a scene in that office once; I forget which film it was. There were about ten people in that room involved with that picture in one way or another. Now every person in that room understood what the point being made was - some question or other had come up - and everyone knew what we were trying to get him to understand. But we couldn't get it across to him - he just could not understand, grasp the point. I'll never forget the forthright, determined set of his face! We never did succeed in..." - the rest was lost in an exasperated, delighted chuckle.

It was in the same darkened MGM studio that Appalachian Spring flourished, written in 1944 for Martha Graham's dance company. "She's a wonderful artist, a marvellous girl, and a truly gifted person who knows exactly what she wants. There's a story which goes with the score of Appalachian Spring. Very often people come up to me after I've conducted it, and they say that when they hear it they can - oh so vividly - see the Appalachians and feel the spring. Well, the fact is when I wrote the work I didn't know what Martha was going to call it! I wasn't thinking about Appalachians at all, I was thinking about Martha Graham, her particular personality and very special style of dancing. When she chose the title I said that's a nice title, where d'you get it. And she told me it was the name of a poem by Howard Crane. 'Does the poem have anything to do with your ballet?' I asked her. 'Oh nothing at all!' she said!"

Copland maintains that it was his spell in Paris which contributed towards the 'American-ness' of much of his music. "It was an example set by the French composers who were so very French in their style. Music had until then been dominated and inspired by the German school, and the French were so very different from all this, that I thought, why can't we branch out in the same way with American music? And in Paris you had Ravel and Stravinsky being attracted by jazz and ragtime. I met Stravinsky at Boulanger's, where she had her five o'clock teas on Wednesday afternoons - and I shook hands with Ravel at these gatherings. I even shook hands with Saint-Saëns - l'm sorry to say he died about two months later (not, I trust, due to my handshake!). He was very lively; even at that date he played the piano very well, and didn't seem at all decrepit. You felt you were living right in the middle of what was happening in Paris in the twenties, instead of just ploughing a furrow with harmony and counterpoint. You were part of a chapter."

With our return to Nadia Boulanger and the Fontainebleau School, our conversation had turned full circle, coming to rest once again with a personality "whose influence on American creative music will some day be written in full". Growing up as he did during a period when satisfactory orchestral recordings were a development of the future, Copland feels that with the availability of symphonic music on disc, composers of the last 50 years or so are more aware than ever of orchestral possibilities in relation to their own music. "...In fact, there's almost too much available. Sometimes I even find myself avoiding it! But it's a good sign that the field is so full of composers now. Where we used to have ten when I was a kid, now there must be a hundred. All that's very healthy." Such optimism is clearly radiated in Copland's performances of his own music – frequent events at the time of our conversation. Concerts with the Paris orchestra, the Brussels Philharmonic, and the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington occupied the weeks on either side of his London appearance. His attitude towards the last nine years, during which he has written practically nothing is as equable as you would expect from so active a performing musician. "I certainly don't feel tortured or bitter," he remarked recently, "only lucky to have been given so long to be creative. I assure you that I do not sit around drooling with disappointment." Evidently not.