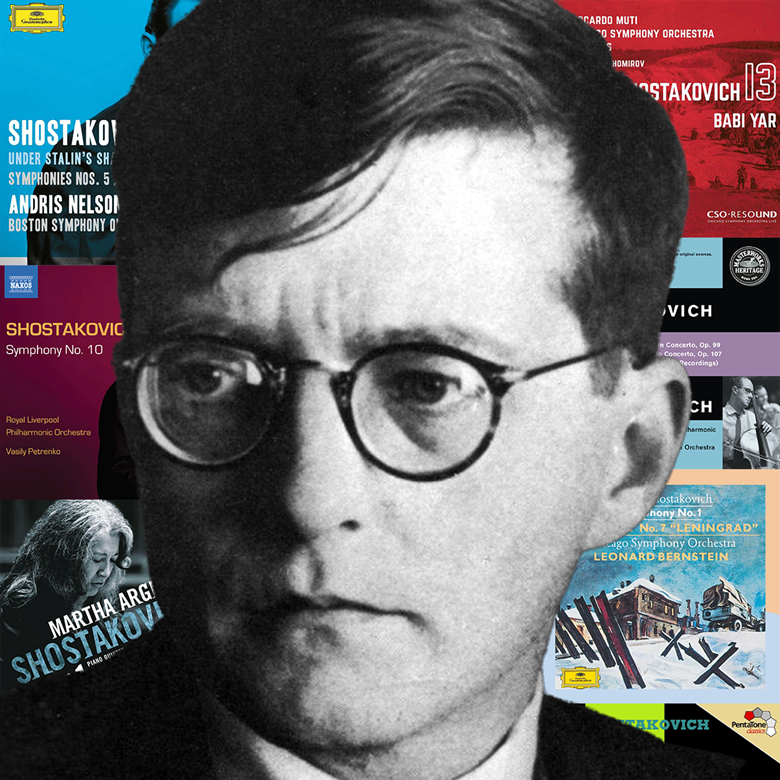

Shostakovich: 30 Recommended Recordings

Wednesday, November 24, 2021

Outstanding interpretations of Shostakovich's music from Rostropovich, Bernstein, Muti, Petrenko, Nelsons and more...

After his death, the government of the USSR issued the following summary of Shostakovich’s work, drawing attention to a ‘remarkable example of fidelity to the traditions of musical classicism, and above all, to the Russian traditions, finding his inspiration in the reality of Soviet life, reasserting and developing in his creative innovations the art of socialist realism and, in so doing, contributing to universal progressive musical culture’.

It wasn’t always like that, despite his three Orders of Lenin and other Soviet honours, for Shostakovich’s life happened to run in tandem with the Communist regime and he frequently fell foul of the authorities for not writing the right type of music. Nevertheless, while Prokofiev and Stravinsky had grown up under the Tsars, Shostakovich was the first and arguably the greatest composer to emerge from Communism.

Cello Concerto No 1

Mstislav Rostropovich vc Philadelphia Ordchestra / Eugene Ormandy

Sony

A Rostropovich signature work, this recording with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia finds him on blistering form.

Cello Concertos Nos 1 & 2

Daniel Müller-Schott vc Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra / Yakov Kreizberg

Orfeo

With roughly a dozen single-disc couplings of the two Shostakovich cello concertos available on CD, a new one needs a sharp profile in order to gain visibility. Müller-Schott and his supporting team have most of the obvious credentials: technique and temperament in abundance, finely judged tempi, and excellent recorded balance and perspective, the soloist placed a little further forward than in some versions, but not distractingly so.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Piano Concerto No 1 in C minor for piano, trumpet & strings, Op 35

Lise de la Salle pf Gabor Baldocki tpt Lisbon Gulbenkian Foundation Orchestra / Lawrence Foster

Naive

Recording of the Month – April 2008

Lise de la Salle's performances are of the highest quality, her rushes of adrenalin balanced by her precise calibration and control. Even with front-runners such as Argerich and Hamelin in the Shostakovich she holds her own, combining her freshness and ebullience with many personal and enchanting touches.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Piano Concerto No 1. Concertino in A minor, Op 94. Piano Quintet in G minor, Op 57

Martha Argerich pf with Sergei Nakariakov tpt Renaud Capuçon, Alissa Margulis vns Lida Chen va Mischa Maisky vc Lilya Zilberstein pf Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana / Alexander Vedernikov

Warner Classics

Argerich’s 1994 DG reading of the Concerto for Piano, Trumpet and Strings is already a benchmark version among modern recordings, complementing the composer’s own technically fallible yet still indispensable 1958 account. But now there is a more natural flow in the slow movement, some previously slightly forced rubatos are smoother, and although the textures are a fraction more richly pedalled, as often needs to be the case for projection to a big audience rather than the microphone, there is no more than an infinitesimal loss of clarity. So if anything Argerich’s playing has the tiniest of edges even over her former self.

Violin Concertos

Alina Ibragimova vn State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia 'Evgeny Svetlanov' / Vladimir Jurowski

Hyperion

Gramophone Award Winner 2021 – Concerto

Editor's Choice – July 2020

Ibragimova’s playing has an unvarnished truth about it. It’s the kind of playing that looks you unblinkingly in the eye and tells it like it is. She’s not afraid to ‘invade your space’ or apply pressure to the sound until its rawness is almost unbearable. But equally she (and Jurowski and his marvellous orchestra) catches the emotional remoteness at the dark heart of the first movement and especially in the moments before the chill of celesta opens up another magic casement to the composer’s inner world and the soloist ascends to create a kind of halo of sound above the deep tolling of the tam-tam.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Violin Concertos Nos 1 & 2

Lydia Mordkovitch vn Scottish National Orchestra / Neeme Järvi

Chandos

This coupling completely explodes the idea of the Second Violin Concerto being a disappointment after the dramatic originality of No 1. Certainly No 2, completed in 1967, a year after the very comparable Cello Concerto No 2, has never won the allegiance of violin virtuosos as the earlier work has done, but here Lydia Mordkovitch confirms what has become increasingly clear, that the spareness of late Shostakovich marks no diminution of his creative spark, maybe even the opposite. In that she’s greatly helped by the equal commitment of Neeme Järvi in drawing such purposeful, warmly expressive playing from the SNO. With such spare textures the first two movements can be difficult to hold together, but here from the start, where Mordkovitch plays the lyrical first theme in a hushed, beautifully withdrawn way, the concentration is consistent. This is a superb disc.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Violin Concertos Nos 1 & 2

Maxim Vengerov vn London Symphony Orchestra / Mstislav Rostropovich

Warner Apex

There’s an astonishing emotional maturity in Vengerov’s Shostakovich. He uses Heifetz’s bow but it’s to David Oistrakh that he’s often compared. His vibrato is wider, his manners less consistently refined, and yet the comparison is well founded. Oistrakh made three commercial recordings of the Shostakovich and one can guess that Vengerov has been listening to those earlier renditions, as there’s nothing radically novel about his interpretation. Some may find Vengerov’s impassioned -climaxes a shade forced by comparison. Yet he achieves a nobility and poise worlds away from the superficial accomplishment of most modern rivals. He can fine down his tone to the barest whisper; nor is he afraid to make a scorching, ugly sound. While his sometimes slashing quality of articulation is particularly appropriate to the faster movements, the brooding, silver-grey ‘Nocturne’ comes off superbly too, though it seems perverse that the engineers mute the low tam-tam strokes. Rostropovich has the lower strings dig into the third movement’s passacaglia theme with his usual enthusiasm. Indeed, the orchestral playing is very nearly beyond reproach.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Violin Concerto No 1

Lisa Batiashvili vn Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra / Esa-Pekka Salonen

DG

The new-found popularity of Shostakovich’s greatest concerto has engendered a flood of state‑of-the-art recordings but few if any are finer than this one. Lisa Batiashvili’s reflective, almost weightless approach in the opening Nocturne is rendered more distinctive by the resonant acoustic of the empty Munich Herkulessaal. For some listeners the suggestion of a lost soul will be enhanced. Orchestra and conductor might be said to be unidiomatic in their coolness and control but for all the lack of local colour the results are spellbinding, even when perfect intonation is momentarily compromised in the interests of heightened expressivity. After a Scherzo which gives the impression of living on the edge, the passacaglia is exceptionally poised and the cadenza more sheerly musical than usual. The finale whizzes to its end without undue triumphalism.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Symphonies Nos 1 & 6

Russian National Orchestra / Vladimir Jurowski

Pentatone

The Russian National Orchestra’s relatively lean, frosty sonority, only partly a product of divided violins, is presented with outstanding fidelity in a spacious acoustic. While both performances are excellent, the Sixth receives the more remarkable interpretation. The second movement is a fierce whirlwind outpacing even Mravinsky, a gambit that only occasionally sounds like a gabble. Perhaps there have been more exhilarating finales but this one has grace as well as the necessary vulgarity. All in all a remarkable achievement.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Symphonies Nos 2 & 11

Mariinsky Chorus and Orchestra / Valery Gergiev

Mariinsky

The Eleventh (1957) is Shostakovich at his most conservative and cinematic, the deployment of revolutionary songs embedding emotional memories superficially in line with the regime’s subsequently expounded ideology of socialist realism in cultural production. Favouring quick‑fire tempi, occasionally too fast for clear articulation, Gergiev avoids getting bogged down in dutiful note-spinning, perhaps tending to undersell the big, graphic moments that may or may not convey subversive intent. Climaxes are not necessarily balanced with an eye to textural clarity and the ambivalent oscillation of the bells at the close lacks precision. While the score has more terror and more warmth than Gergiev reveals, admirers will find plenty of compensating flair and drive. The sound is vivid and the booklet includes performer listings, sung texts and translations.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Symphonies Nos 3 & 10

Mariinsky Chorus and Orchestra / Valery Gergiev

Mariinsky

However many performances or recordings of its great first movement you have heard, you will be lucky to encounter one as compelling as this. Gergiev takes fractionally faster tempi than the norm, allowing for subtle expressive retardations that do not disturb the flow, and making the most of the magnificent arch-shaped structure. This he balances with a Scherzo of exceptional weight (clocking in at an unsensational 4'29" but feeling absolutely justified). This superbly recorded disc remains one of the few indispensable Shostakovich CDs of recent years.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Symphony No 4

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra / Vasily Petrenko

Naxos

Gramophone Awards Shortlisted 2014 – Orchestral

Recording of the Month – November 2013

The opening goes off like a cartoon alarm clock, shrill and insistent, the ensuing march more satirical, almost more Prokofiev than Shostakovich in Vasily Petrenko’s hands. This is less the child of Mahler’s Third, more death takes a holiday than summer marches in. Significantly, Petrenko comes to this piece – or appears to – without even scant acknowledgement of its structural anomalies, its weird and wonderful digressions, transformations and mutations. It’s a work teetering between the rational and irrational, the comic and tragic, the real and the imagined. Just when you think it’s slipping into abstraction, something happens to make you think otherwise. Petrenko makes following its thought processes, its phantasmagorical journeying between worlds, so much easier. He makes perfect sense of the seemingly senseless.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Symphonies Nos 5 & 9

Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra / Bernard Haitink

Decca

Gramophone Award Winner 1982/3 – Engineering

This comes as a breath of fresh air after Rostropovich's DG account. This, too, brings some very impressive playing from the Washington orchestra and there is no doubt as to the intensity of feeling that Rostropovich brings to this score. But this very intensity often disturbs the natural musical flow in favour of expressive point making. No one playing this recording can fail to be impressed for the sound has an imposing clarity and depth but play the Scherzo in this version and follow it with the Haitink, and there is no question of the superiority of the latter. Those who see eye-to-eye with Rostropovich in the various interpretative decisions he makes need not hesitate but for most collectors Haitink's sane and finely-shaped account will be the one to have.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Symphonies Nos 1 & 7

Chicago Symphony Orchestra / Leonard Bernstein

DG

The Leningrad Symphony was composed in haste as the Nazis sieged and bombarded the city (in 1941). It caused an immediate sensation, but posterity has been less enthusiastic. What business has the first movement’s unrelated long central ‘invasion’ episode doing in a symphonic movement? Is the material of the finale really distinctive enough for its protracted treatment? Michael Oliver, in his original Gramophone review, wrote that in this performance ‘the symphony sounds most convincingly like a symphony, and one needing no programme to justify it’. Added to which the work’s epic and cinematic manner has surely never been more powerfully realised. These are live recordings, with occasional noise from the audience (and the conductor), but the Chicago Orchestra has rarely sounded more polished or committed. The strings are superb in the First Symphony, full and weightily present, and Bernstein’s manner here is comparably bold and theatrical of gesture. A word of caution: set your volume control carefully for the Leningrad Symphony’s start; it’s scored for six of both trumpets and trombones and no other recording has reproduced them so clearly, and to such devastating effect.

Symphonies Nos 5, 8 & 9

Boston Symphony Orchestra / Andris Nelsons

DG

Gramophone Awards Shortlisted 2017 – Orchestral

Editor's Choice – August 2016

The Fifth Symphony is quite marvellous and like the Tenth should dominate the catalogue for a long time to come. I love the way the first subject sounds for all the world like a remnant of Tchaikovsky’s legacy as opposed to ‘a Soviet artist’s reply to just criticism’. The romantic nature of the piece is lushly served – nowhere more so than in the ravishing Largo, infused as it is with the spirit of star-crossed lovers (Shostakovich almost invoking the fragrant world of Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet) and quite wonderfully chronicled by the Boston Symphony strings – as downy in repose as they are intense in extremis. The entire movement sounds ‘headier’ than I’ve ever heard it since the famous Previn/LSO recording from the 1960s. The hushed celesta-flecked coda is breathtaking.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Symphony No 10

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra / Vasily Petrenko

Naxos

Gramophone Award Winner 2011 – Orchestral

Petrenko’s Shostakovich cycle goes from strength to strength. This is a symphony that places a high premium on a conductor’s ability to shape long lines with subtle inflections of tempo and structural accent, especially in the epic first movement’s journey from mystery to tragic climax and back. In this respect Petrenko lives up to – even surpasses – the greatest of his compatriots, joining Karajan’s account as the most satisfying.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Symphony No 10

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra / Herbert von Karajan

DG

Few works give a deeper insight into the interior landscape of the Russian soul than Shostakovich’s Tenth, and this is a powerful and gripping account. Karajan has the measure of its dramatic sweep and brooding atmosphere, as well as its desolation and sense of tragedy. There are many things here (the opening of the finale, for example) which are even more succesful than in Karajan’s 1966 recording, though the main body of the finale still feels too fast – however, at crotchet=176, it’s what the composer asked for. His earlier account of the first movement is for some more moving – particularly the poignant coda. However, the differences aren’t significant and this is hardly less impressive.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Symphony No 10

Boston Symphony Orchestra / Andris Nelsons

DG

Gramophone Award Winner 2016 – Orchestral

Recording of the Month – August 2015

Andris Nelsons’s first (live) recording as Music Director of the Boston Symphony is quite something. It carries the title ‘Under Stalin’s Shadow’ though, of course, the Tenth Symphony – premiered just months after Stalin’s death in 1953 – was the point at which Shostakovich emerged from that shadow defiantly brandishing his own musical monogram – DSCH – like a medal of honour. But while the Tenth is in itself a before-and-after-Stalin chronicle, Nelsons has added a preface in the shape of the stupendous Passacaglia from the composer’s opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District – the piece which first found disfavour with the dictator and his regime.

So shock-and-awe arrives with a vengeance in the screaming organ-like chords which portend Katerina Izmailova’s destiny – the State bearing down on this liberated woman for the crimes to which she has been driven. It is the musical embodiment of oppression, this extraordinary interlude, and the irony is that Stalin should not recognise it as such but rather find offence in its crushing dissonance. And, my goodness, Nelsons lays down the monster climax with almost obscene relish, howls of derision from the woodwind choir and the Boston trumpets recalling a thrilling stridency from days of yore when the principal from the Münch and Leinsdorf eras would lend a steely, blade-like gleam to the tutti sound.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Symphony No 13

Alexey Tikhomirov; Chicago Symphony Orchestra & Chorus / Riccardo Muti

CSO Resound

At first you may perceive a lack of urgency. The opening elegy to the un-memorialised victims of ‘Babi Yar’ is slower even than Haitink’s, unfolded with reverence as much as anger. There are theatrical touches and climaxes of bludgeoning power but little of the urgent specificity and attack of Kondrashin’s live relay of 1962 (the work’s second performance). The strength of Muti’s reading lies less in its patient nobility than in the beauty and tenderness he subsequently extracts from writing that can seem sketchy or bald. Approaching his retirement from Chicago he finds unique qualities in the closing movement, ‘A Career’. For me there is no more affecting account of its musings on the vagaries of intellectual freedom and dutiful professionalism. The final bars have the poised serenity once associated with Carlo Maria Giulini, albeit not in this repertoire.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

The Golden Age

Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra / Gennadi Rozhdestvensky

Chandos

This first complete recording is a major coup for Chandos. Admittedly not even their flattering engineering can disguise a certain lack of confidence and idiomatic flair on the part of the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra. But don’t let that deter anyone with the least interest in Shostakovich, or ballet music, or Soviet music, or indeed Soviet culture as a whole, from investigating this weird and intermittently wonderful score. A really fascinating disc.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

‘The Dance Album’

Philadelphia Orchestra / Riccardo Chailly

Decca

Although entitled ‘The Dance Album’, interestingly only one of the items on this disc (The Bolt) is actually derived from music conceived specifically for dance. However, what the disc reveals is that Shostakovich’s fondness for dance forms frequently found expression in his other theatrical/film projects. All the performances on the disc are superbly delivered and the recorded sound is excellent.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

‘The Jazz Album’

Peter Masseurs tpt Ronald Brautigam pf Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra / Riccardo Chailly

Decca

Shostakovich’s lively and endearing forays into the popular music of his time were just that, and light years away from the work of real jazz masters such as, say Jelly Roll Morton or Duke Ellington. And yet they do say something significant about Shostakovich’s experience of jazz, as a comparison of these colourful, Chaplinesque Jazz Suites with roughly contemporaneous music by Gershwin, Milhaud, Martinu, Roussel and others will prove. Shostakovich engaged in a particularly brittle, almost Mahlerian form of parody – his concert works are full of it – and that’s what comes across most powerfully here. Besides, and as annotator Elizabeth Wilson rightly observes, ‘real’ jazz was treated with suspicion in Soviet Russia and Shostakovich’s exposure to it was therefore limited.

String Quartets Nos 1-15. Two Pieces

Emerson Quartet

DG

The Emersons have played Shostakovich all over the world, and this long--pondered cycle sets the seal on a process that has brought the quartets to the very centre of the repertoire – the ensemble’s and ours. While some listeners will miss the intangible element of emotional specificity and sheer Russianness that once lurked behind the notes, the playing is undeniably committed in its coolness, exposing nerve-endings with cruel clarity. The hard, diamond-like timbre of the two violins (the leader’s role is shared democratically) is far removed from the breadth of tone one might associate with a David Oistrakh, just as cellist David Finckel is no Rostropovich. But these recordings reveal surprising new facets of a body of work that isn’t going to stand still. This is a Shostakovich cycle for the 21st century.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

String Quartets Nos 1-15

Fitzwilliam String Quartet

Decca

Gramophone Award Winner 1977 – Chamber

The Fitzwilliam Quartet recorded their cycle originally in the mid-1970s, shortly after a concentrated period of study with the composer. Nos 4 and 12 won a Gramophone Award in 1977. Despite being recorded in analogue, the sound-quality is still remarkably good. The music of Shostakovich is perhaps the most personal of any written in the twentieth century. For that reason, and because the quartets encompass the complete gamut of human emotion, one close friend of Shostakovich has described him as 'the Beethoven of our age'. The quartets are well worth getting to know and the performances by the Fitzwilliam Quartet, despite being 15 years old, still seem to reach the heart of the composer's intentions.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Piano Trios Nos 1 & 2. Seven Romances on Verses by Alexander Blok, Op 127

Susan Gritton sop Florestan Trio

Hyperion

This isn’t the first CD to group Shostakovich’s two piano trios with his late Romances to poems by Alexander Blok but, for the freshness and excellence in every aspect of performance and production, it would be the pick. The songs originated in a request from Rostropovich for a work for his wife, Galina Vishnevskaya, with cello. A ‘confessional’ tone in the writing can be sensed, as if Shostakovich’s own anguish and compassionate feelings were surfacing in his response to the words. How clever this composer was at aligning himself with a poet’s voice and giving projection to intimate and personal feelings.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Preludes & Fugues for piano, Op 87

Igor Levit pf

Sony

Recording of the Month – October 2021

To the Bach-inspired numbers Levit brings a characterful immediacy, whether in the bustling E major two-voice Fugue of No 9, for instance, or the Prelude of No 10, which quotes directly from the ‘48’. And the 14th Prelude in E flat minor has never sounded quite as starkly anguished as it does here, with a folk-like melody against a tremolo backdrop.

Levit is compelling, too, in the concluding numbers of each half: the Passacaglia of No 12 emerges from the rumbling depths, while he patently enjoys the jazzy Fugue, with its 5/4 time signature. Levit outdoes Nikolayeva in grandeur in the final Prelude in D minor, the bruising closing harmonies potent indeed. The Fugue combines a Bachian inevitability with a sense of the epic that is Shostakovich’s own and Levit isn’t afraid to let rip, but always with that cushioned sound that has become a trademark.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Preludes & Fugues for piano, Op 87

Tatiana Nikolayeva pf

Hyperion

Gramophone Award Winner 1991 – Instrumental

The recording is clear and atmospheric, and the playing has power, grandeur, character, intellectual clarity and unforced intensity.

Preludes for piano, Op 34

Olli Mustonen pf

Decca

Gramophone Award Winner 1992 – Instrumental

Olli Mustonen's playing is, simply, phenomenal. Vladimir Viardo's racing semiquavers in No 5 of the Shostakovich may be smoother, but Mustonen gives us something altogether more alive – a breathtaking cascade of notes running smack into a wonderfully improbable perfect cadence.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Suite on Poems by Michelangelo

Dmitri Hvorostovsky bar Ivari Ilja pf

Ondine

Gramophone Awards Shortlisted 2016 – Solo Vocal

Editor's Choice – December 2015

Hvorostovsky offers searching readings of these rugged, jagged songs which are full of resignation and bittersweet regret, of loss and separation. The later songs anticipate death, yet the final offering, ‘Immortality’, thumbs a nose at death in an insolent piano part – death cannot destroy the artist’s legacy – where the nursery-rhyme simplicity is reminiscent of the Fifteenth Symphony’s ‘toyshop’.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

The Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District

Sols incl Galina Vishnevskaya sop Nicolai Gedda ten Dimiter Petkov bass; London Philharmonic Orchestra / Mstislav Rostropovich

Warner Classics

Rostropovich’s cast has no weak links to it. More importantly, he gives a full-blooded projection of the poignant lyricism that underlies the opera’s brutality. Vishnevskaya’s portrayal of Katerina is at times a bit too three-dimensional, you might think, especially when the recording, which favours the singers in any case, seems (because of her bright and forceful tone) to place her rather closer to you than the rest of the cast. But there’s no doubt in her performance that Katerina is the opera’s heroine, not just its focal character, and in any case Gedda’s genially rapacious Sergey, Petkov’s grippingly acted Boris, Krenn’s weedy Zinovy, Mroz’s sonorous Priest, and even Valjakka in the tiny role of Aksinya, all refuse to be upstaged.

Read the review in Gramophone’s Reviews Database

Never miss an issue of Gramophone magazine – subscribe today