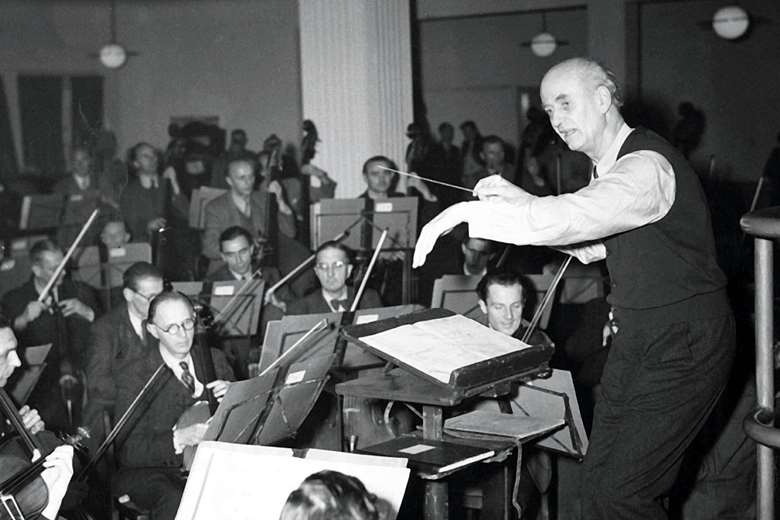

Classics Reconsidered: Furtwängler’s pioneering 1944 recording of Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony

Friday, November 29, 2024

Peter Quantrill and Christian Hoskins return to Wilhelm Furtwängler’s pioneering 1944 recording of Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony

The original Gramophone review

Bruckner Symphony No 9 Berlin Philharmonic / Wilhelm Furtwängler (DG)

The truth is that – as Hans Keller has said – Furtwängler was the opposite of a gramophone record. It is difficult to live with a fixed-for-ever Furtwängler performance – he did not live with his own performances, in fact, but lived a new one each time. A record of Furtwängler, unlike one of any other great conductor is not a definitive preservation of a final, considered interpretation – the result of years spent aiming at the most faithful account possible of the score; it is an arbitrary crystallization of one stage in a constantly changing process – of an inspired re-enactment of a work, as it happened to occur at that particular moment. And ‘inspired’ is the word: there was never a dead bar in any performance by Furtwängler. There might be things which seemed completely unacceptable: I certainly cannot take the frenzied accelerando used in the first movement of Bruckner’s Ninth, though I might well have done at a concert, with the man living this in front of me. But to approach any great piece of music through his peculiar style – the massive spread of fortissimo chords, the sustained weight of the accents, the uniquely monumental phrasing – is to find depths in it which one had never suspected. One believes for the moment that Furtwängler alone has penetrated to the composer’s hidden meaning, finding a ferocious wildness in Bruckner. If I had plenty of money, I would buy two different discs of any great work recorded by Furtwängler – his own and one by an equally great, but more ‘normal’ conductor. The latter would be to live with, the former for re-inspiration at long intervals. The sound of the Bruckner, alas, is pretty dim, and one has to listen with the ear of faith – or better, with the score, with which one can pick out many of the nearly inaudible strands of the texture. Deryck Cooke (12/63)

Peter Quantrill It can take us aback to reflect that the Ninth Symphony was less than a decade old, in the state that Bruckner left it on his deathbed, when the 20-year-old Furtwängler first conducted it at his first public concert, in February 1906. The symphony must have meant something special to him ever thereafter. He introduced No 7 to his repertoire in 1912, Nos 4 and 8 in 1914, No 5 in 1919 and so on. He seldom returned to the Ninth, however, while his performances of Nos 4 and 7 number into three figures.

Christian Hoskins Yes, it’s regrettable that we have only the one recording of a work that’s so suited to Furtwängler’s approach to Bruckner. In some of the other symphonies, it can feel as if he’s wrestling the material into intense and dramatic musical statements which are uniquely persuasive but beyond anything envisaged by the composer. In the Ninth, by contrast, the music conveys doubt, conflict and desolation in a way not heard in the earlier works, marked by chromatically restless harmonies and the overwhelming dissonant chord at the climax of the Adagio. It would have been fascinating to have been able to hear his interpretation of such a work at different times.

PQ Given the variable nature of most other pre-1960 Bruckner performances (in terms of playing and engineering), this sole extant representation of Furtwängler in No 9 is unusually consistent at a technical level. It was given under concert-broadcast conditions in Berlin without an audience. So we are in a good position to evaluate the interpretation in itself, notwithstanding other context impossible to ignore, including its date: October 7, 1944. Four days later he gave it once more, at the abbey of St Florian, with the Reichs-Bruckner-Orchester, formed at Hitler’s behest. My principal reservation concerns the relatively constricted mono sound, which conveys only a partial and generic impression of Furtwängler’s handling of texture.

CH The dynamic range is surprisingly good for its time, and the balance of the orchestral groups is for the most part acceptable, though the oboe is almost inaudible at around both 6'18" in the opening movement and 1'36" in the Scherzo, and sounds unpleasantly thin at 14'45" in the Adagio. That’s preferable to the bleat one hears at 5'54" in the same movement, though!

PQ The accelerando towards the first tutti from 1'30" is quintessential Furtwängler, isn’t it: not in the score, yet strongly motivated, and preparing the ear for that first mighty statement which emerges almost pianistically as a sung phrase, however jagged the material on the page. This in turn prepares the way for the plastic, urgent moulding of the second subject (from 3'28") – which is ardent and tender in a way that most Bruckner interpreters for the next few decades contrived to forget or overlook, naturally burgeoning and blooming at its climax (4'40") just as we’d expect the second act of Tristan und Isolde to unfold.

CH Indeed, the subtlety of the transition to the second subject struck me also, aided as it is by an exemplary observance of dynamics. Interestingly, he chooses not to observe the marked accelerando at bar 161 (6'44') and the subsequent arrival of the third subject shortly after 7'06" feels slightly slow to me. One might have expected Furtwängler to have whipped up a storm in the various climactic episodes of the development section, but he holds the tempo surprisingly steady.

PQ The reining in at 6'24" doesn’t bother me except that the return to the second theme doesn’t pick the pulse back up, and the next few minutes wander. Indeed, the the first theme’s return 10 minutes in is surely slower than its original appearance. At 11'04" the pulse becomes unaccountably rocky in the dialogue between wind and brass, and a decisive grip is only recovered with the tutti. At this point, the direction of the whole movement becomes much more confident, returning to the firm shape established at the outset. Thereafter, timing and shaping are perfect, the timpani roll to begin the coda thoroughly prepared, the momentum grim but never loftily impersonal or brutal. It’s a thoroughly human drama.

CH It’s a pity that the timpani enters fractionally late at 19'33" in the third subject, but – as is so often the case in a Furtwängler performance – it has an eruptive, expressive power that’s intensely involving. The remainder of this section builds with increasing momentum and intensity to an almost overwhelming climax.

PQ In direct continuity, the Scherzo is seized from the outset by forces beyond its control, recognisably a translation and evolution of the Scherzo in Beethoven’s Ninth.

CH Furtwängler’s tendency to push on the tempo at key points certainly conveys the impression of a juggernaut almost out of control. Despite the recording quality, the layering of horns, trombones and trumpets from 0'35" is wonderfully transparent, something that’s often missing in modern recordings. In the Trio, the F sharp minor melody for cellos at 4'30" is illuminated with a haunting sense of fantasy.

PQ Yes, to contradict myself, this is where the weirdness comes through. Whether or not the climax of the Trio, the exaggerated rallentando for the transfer of that melody to the strings, is intentionally a proto-Mahlerian parody of the dance is hard to say.

CH It’s in the Adagio that I most feel the performance being shaped by Furtwängler’s vision of the piece, or at least, his vision as it stood at that time and in that place. At the very start, for example, he eschews Bruckner’s ff marking in favour of a gradual increase in volume for the first violins that emulates the opening of Parsifal. The same thing happens when the opening theme repeats later. Manfred Honeck does something similar in his Pittsburgh SO recording (12/19).

PQ Following Robert Haas, Furtwängler compared Bruckner to Meister Eckhart: as a transcendental mystic ‘whose appointed task was … to weave the power of God into the fabric of human life’. The nobility and restraint of his address to this opening is so utterly different in sound and spirit from the expressionist angst of Günter Wand, isn’t it? – although François-Xavier Roth (8/24) achieves a similar mood at a quicker tempo, and emulates Furtwängler’s elastic pulse. In fact, the likes of Bruno Walter and Otto Klemperer used to lead the Adagio much more urgently (a practice revived not only by Roth but also by Marcus Bosch and Sir Roger Norrington). It was only after the war that the movement became set in marble.

CH I sense the darker, more introspective sections engaging Furtwängler the most. The Adagio’s opening statement builds to a powerful climax at 2'21", as indicated in the score, but something is held in reserve compared with the ecstatic outpourings of Daniel Barenboim, Eugen Jochum and Herbert von Karajan. By the time of its final incarnation at 20'59", after the crushing climax of the movement, its presentation is relatively subdued.

PQ I’m not sure I follow you here. I don’t hear anything held back about the unwritten subito piano at 2'36"! A kind of lofty communion is the keynote of the movement in modern sensibility, I think, whereas Furtwängler has something much more visceral in mind. He talks about Bruckner in general as composing ‘struggles against demonic forces’ and ‘music of blissful transfiguration’, and in this Adagio presents them both in direct opposition.

CH Maybe I’m reading too much into the date of the performance, but it seems to me that the demonic forces are in the ascendancy. Consider, for example, the depth of feeling conveyed by the passage for horns, Wagner tubas and tremolo strings that follows. And the performance is especially compelling in the second subject, communicating weariness and melancholy in equal measure, with the violins especially expressive at 6'29". Compared with what’s gone before, the pacing is surprisingly steady.

PQ But it’s precisely the steadiness of pulse in this material that lends such cumulative force to the espressivo moulding of the first subject and its reiterations. It reminds me in this way of the D major/minor tension in the first movement of Mahler’s Ninth. Sometimes that conflict leads to some crudely blatant voice-leading, such as the trumpet at 10'32" – or is that the recording? At this distance, I find it hard to discern the motivation behind the winding-up of pulse around 12'10" except as some private revelation experienced in the moment.

CH I’m reminded not only of Mahler but of Schoenberg and the fifth of his Five Orchestral Pieces when it comes to the striking six-bar passage heard at 15'21". Furtwängler conveys expressionistic vehemence in this music, as he does the radiance of the descending strings at 16'18". I must admit, however, when it comes to the movement’s climax, I miss the impact found in more modern recordings. As for the coda, the performance suggests to me resignation rather than the acceptance and serenity heard in more recent interpretations.

PQ But then this individuality, this willed submission to the present, is what sets Furtwängler apart from most interpreters, old and new. The Adagio’s climax and coda surely fulfils both. Robert Simpson observed that a conductor could hold that agonising chord as long as it felt right, so too the gaping silence in its wake, and he must have had this performance in mind. Is this one-off performance more than the sum of its best parts? I’m not sure. Is it quintessentially Furtwängler? Certainly.