Classics Reconsidered: Elgar’s The Kingdom (LPO / Sir Adrian Boult)

Geraint Lewis and Jeremy Dibble

Friday, June 14, 2024

Geraint Lewis and Jeremy Dibble revisit the first ever full recording of Elgar’s The Kingdom, made by Sir Adrian Boult in 1968

The original Gramophone review

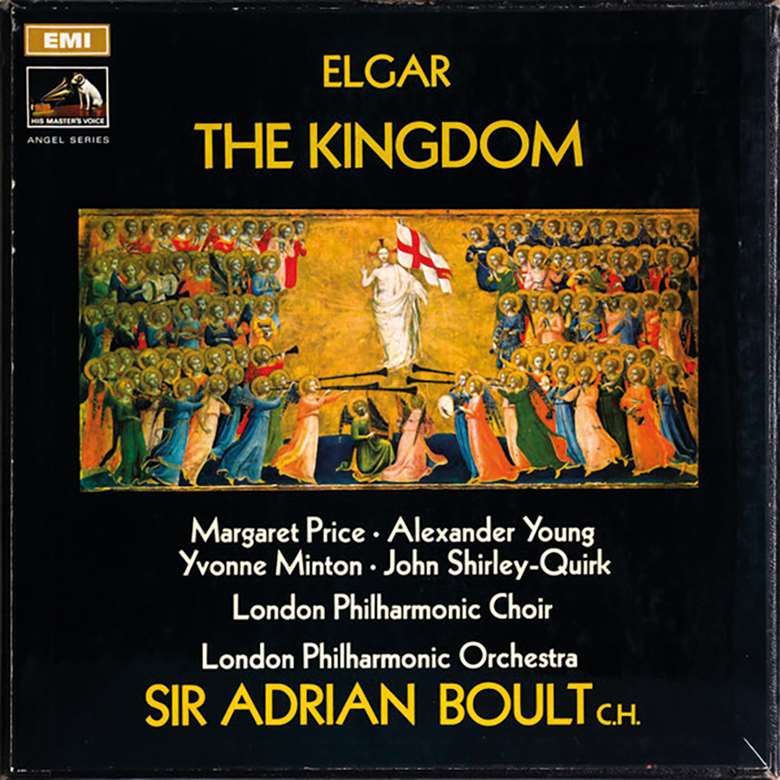

Elgar The Kingdom

Margaret Price sop Yvonne Minton contr Alexander Young ten John Shirley-Quirk bass London Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra / Sir Adrian Boult (EMI)

Many readers will know from EMI’s announcements that Elgar’s oratorio, The Kingdom, was scheduled for recording. They, as all others to whom this is news, will rejoice that their often expressed and fervent wishes over the years at last find fulfilment: and it was an imaginative gesture to plan this first-ever recording of the great work as a birthday tribute to Sir Adrian Boult who, incredible though it sounds, will be 80 years old on April 8th.

The Kingdom is one of Sir Adrian’s favourite works and the superb interpretation he gives of it, born of long experience, reveals the true stature of the oratorio. Indeed, Sir Adrian almost wins me over to his considered opinion, given in the booklet, that ‘there is a great deal in The Kingdom that is more than a match for Gerontius … I feel it is a more balanced work and throughout maintains a stream of glorious music, whereas Gerontius has its ups and downs’. In his interesting historical note on The Kingdom, also in the booklet, Percy Young describes it as ‘essentially reflective … the slow movement, so to speak, of the whole intention of the (uncompleted) trilogy’.

That is well put. The Kingdom is not so grand or dramatic as The Apostles but it is more human and intimate. Elgar’s portrait of Judas in The Apostles was original and vivid and, in comparison with it, Peter was a shadowy figure; but in The Kingdom he stands out as the prince of the Apostles, with authority and a fully formed character. John and Mary come much nearer to us, also, in this work.

The recording is one of the finest in the field of choral music EMI have ever made; perhaps, indeed, the finest of all. As I have said, Sir Adrian Boult has inspired his forces to give of their best and you feel that every one of them – soloists, chorus and orchestra – are participating wholeheartedly not only as their tribute to a great conductor and a personality of rare charm, integrity and simplicity, but also to do full justice to the superb music of Edward Elgar. Christopher Bishop has again shown his outstanding qualities as a producer of choral music and the engineers have also done splendid work.

One thing remains. You have given us The Kingdom, EMI, for which we are truly grateful: but now please let us have The Apostles, not only for its own sake but so that we might play the one work after the other, follow the relationship of the themes shared between them, and so be able to evaluate the whole great undertaking. Alec Robertson (4/69, abridged)

Geraint Lewis I’m sure that many readers will be surprised to realise that Elgar’s 1906 oratorio The Kingdom had to wait until 1969 for its first complete recording to be issued on LP – and it’s just as surprising, in a way, that its related Birmingham Festival predecessor The Apostles, of 1903, was only first released on record in 1974. These major EMI projects were made and released to mark Adrian Boult’s 80th and 85th birthdays respectively, and naturally represent huge landmarks in the Elgar discography. But I venture to suggest that hardly any premiere recording of a great choral masterpiece can have enjoyed such powerful and eloquent advocacy as this remarkable account of The Kingdom.

Jeremy Dibble I was but 11 years old when this LP came out, but I remember vividly becoming aware of the recording as I awakened to Elgar’s music during my mid-teens in the 1970s. I recall particularly the momentum that the first releases of these two great oratorios created in what was such an exciting period of re-evaluation of Elgar generally. In fact, before I heard Boult’s recording, the only part of The Kingdom with which I was familiar was Elgar’s own recording of the Prelude, which he made with the newly founded BBC SO (formed by Boult in 1930) in Studio 1, Abbey Road, on April 11, 1933. Even then my impression of the music was that it embodied the composer at the very height of his creative confidence.

GL I had a remarkably similar experience! As a young teenager I bought Anthony Griffith’s remarkable 1970 transfer to LP of Elgar’s own 1930 recording of the First Symphony with the LSO – it just jumped out of the grooves, so vivid was the performance, and there as a coupling was the 1933 BBC SO version of the Prelude to The Kingdom. I was instantly transfixed by the sheer magic, the noble intensity and lyrical fervour of this richly clothed orchestral music. At this very early point for me, I didn’t actually know any of Elgar’s choral works, even The Dream of Gerontius – but I soon borrowed this newish Boult recording of The Kingdom and fell immediately under its spell. I will never forget the impact of Margaret Price singing ‘The sun goeth down’ – a heart-stopping moment at any age. I think the 1930 Symphony No 1 recording was made in London’s Kingsway Hall, which is where Boult’s The Kingdom was captured in 1968 – a wonderful venue with a gloriously spacious sound.

JD Besides the splendid playing of the LPO, one of the great strengths of the recording is the line-up of soloists. John Shirley-Quirk as St Peter and Alexander Young as St John are superb in their individual roles as well as together in their uplifting duet. Yvonne Minton and Margaret Price are also well matched in that magical section ‘At the Beautiful Gate’, where Elgar’s instrumentation is almost chamber-like in its delicacy and detail. But, yes, you’re right: Margaret Price is resplendent in ‘The sun goeth down’, a scene which points up the quasi-operatic, indeed Wagnerian, nature of Elgar’s Birmingham oratorios. In fact, the climactic part of this unique scene in the Elgar literature is, at times, quite redolent of Strauss, and recalls similar passages from In the South, which was composed two years earlier and had no doubt been inspired by the frenzy of interest in Strauss’s music in England in 1903 after the composer’s visit to conduct his tone poems in the capital. I also think that this scene, which Agnes Nicholls (who sang in the premiere) made her own, was hugely influential on Ode to a Nightingale – composed for Nicholls by her husband, Hamilton Harty, in 1907 for the Cardiff Musical Festival. What is more, Harty, by then considered the finest accompanist in London, must have acted as repetiteur for her.

GL Harty was obviously a hit at the Cardiff festival because at the next one, in 1910, he premiered his great orchestral poem With the Wild Geese, and Nicholls also appeared. As a Cardiffian I’m pleased that you’ve mentioned this now-forgotten event, which in its heyday could be considered alongside the Leeds and Birmingham choral festivals, and in 1904 featured what must have been the first Welsh performance of The Dream of Gerontius. And mention of Nicholls takes me back to Boult: in a note attached to the original booklet for his recording of The Kingdom he recalls being present at one of Elgar’s last performances, at the Three Choirs Festival, when Nicholls came out of retirement to save the day because another singer was indisposed. Boult reports that Elgar seemed bored by the whole thing and disaster was only averted when Nicholls’s extraordinary intensity in singing ‘The sun goeth down’ suddenly galvanised him to a white heat of inspiration right to the end. I’ve always been intrigued to find that Boult, with such vivid memories to draw upon, felt so passionately that The Kingdom was a greater work than Gerontius – I wonder what you feel about this controversial viewpoint.

JD Controversial it may be, but I have never been in any doubt that The Kingdom is the greatest of all his oratorios. Much as I love Gerontius, and much of The Apostles (especially Judas’s agonised monologue and the grand climax of the finale), I feel The Kingdom exudes a palpable sense of confidence and belongs to that group of Elgar works – the Introduction and Allegro, the First and Second Symphonies and the Violin Concerto – which epitomise the beating heart of the composer’s musical style in terms of their wealth of material. In fact, one could argue that there is almost a surfeit of thematic ideas (this is certainly true of the First Symphony and Violin Concerto), but this potential defect is so diminished by the strength, distinctiveness and characteristic orchestration of these ideas, attributes which give the Prelude such a sense of Schwung. Take, for example, the ‘slow march’ of the ‘New Faith’ in D flat, the magnificent Pentecost march for chorus (‘He who walketh upon the wings of the wind’) or the closing prayer material, all of which are particular to The Kingdom; these are exceptional, deeply memorable motifs. I would also say that Elgar’s tonal structure is also much tighter in this oratorio (the role of E flat major is especially important) than in either Gerontius or The Apostles.

GL That sense of the score’s tonal architecture allied to its dramatic structure takes me straight back to Boult’s infallible mastery of the long view: his ability to conceive a performance as if in one breath which no subsequent recording, to my mind, has surpassed. And if we tend to think of him now as a supreme orchestral conductor, it’s worth noting that in his day he was thought of as a great choral director, too – and in 1968 he certainly inspired the London Philharmonic Choir to remarkable heights of eloquence and fiery passion while simultaneously keeping a tight grip on everything else in play.

JD Certainly. We’ve mentioned the fine array of soloists on this recording, but the chorus also does a fine job. Elgar’s use of the chorus is particularly orchestral in The Kingdom (which is also reflected in many of his later ‘instrumental’ part-songs such as Go, song of mine). Yes, there are examples of more traditional choral writing, but in so many other instances the voices interact with the quintessential presence and momentum of the orchestra as part of Elgar’s unique homogeneous sense of choral and orchestral ensemble, particularly the election of Matthias and the conclusion of Part 1, as well as the magnificent Pentecost scene (Part 3) and the Lord’s Prayer in Part 5. All this was a revelation when I first heard Boult’s recording more than 50 years ago, and I am still moved by its originality and freshness today. Discussing Elgar’s greatest choral masterpiece here has also whetted my appetite for its performance on the last night of this year’s Three Choirs Festival in Worcester.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2024 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue of the world's leading classical music magazine – subscribe to Gramophone today