Classics Reconsidered: Handel’s Messiah (English Chamber Orchestra / Charles Mackerras)

Friday, July 12, 2024

Richard Wigmore and Lindsay Kemp assess how Charles Mackerras’s 1966 recording of Messiah stands up more than half a century later

The original Gramophone review

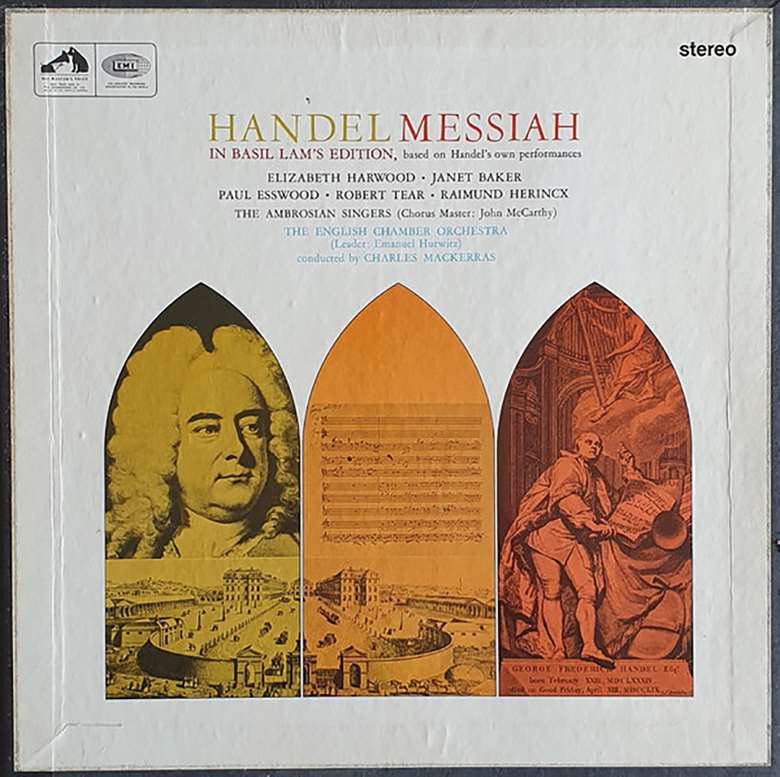

Handel Messiah

Harwood sop Baker contr Esswood counterten Tear ten Herincx bass Ambrosian Singers, English Chamber Orchestra / Charles Mackerras (HMV)

Colin Davis’s Messiah and this one are the most exciting performances I’ve ever heard. The forces used are very similar, resulting in a clarity that was impossible in the mammoth performances of the past. The chorus numbers about 40, a proportion of the altos being male, giving the alto line a cutting edge that raises it from the usual rather characterless anonymity. Mackerras uses a more Handelian proportion of oboes and bassoons; six and four as opposed to two of each. Bassoon tone is agreeably apparent on the continuo line in many items; as also in the Davis, though less often and less assertively. Mackerras has both organ and harpsichord for the continuo, and occasionally uses both at once with great effect. There can be no such thing as ‘the original version’ of Messiah, if only because what was sung at the premiere is not the same as what is in Handel’s autograph. There is nothing either right or wrong in breaking away from the choice of items that happens to have become conventional during the last century. Lam and/or Mackerras offer some variants on the usual pattern, none of which has been recorded before. I feel a great deal of admiration for what Mr Lam has contributed here, as also for the spirit and integrity of Mackerras’s conducting. This is a most alive and fascinating performance, with splendid orchestral playing, soloists who all seem at the very top of their form, and excellent recording quality. The articles by Lam and Mackerras in the accompanying booklet are scholarly, thought-provoking, and very readable. Roger Fiske (3/67)

Richard Wigmore Before the mid-1960s there’d been fitful attempts to strip away encrusted Victorian tradition and present the nation’s choral icon with modest forces and Handel’s own orchestration. But two recordings issued in quick succession in 1966 and 1967, by Colin Davis and Charles Mackerras, staked new claims to ‘authenticity’. Both caused a stir, and their relative merits were hotly debated. (Fiske in fact compared the two throughout his original review, which is given in a severely abridged version above.) Mackerras’s version, based on Basil Lam’s scholarly edition, was certainly the more radical. Producer Christopher Bishop even went so far as to suggest that this was ‘Messiah as Handel would have done’. To put it mildly, that begs a few questions!

Lindsay Kemp Ah yes, if the ‘early music movement’ (of which this recording can be considered an early product) has learnt one important thing, it is not to make claims like that any more. Mackerras’s Messiah was shaped by recent researches into 18th-century performance practice still observed by the best recordings today, yet how different it sounds from the period-instrument versions that followed on from Christopher Hogwood’s pioneering Messiah only a dozen or so years later! And what variety we have continued to witness since! Mackerras found radical clarity, brightness and definition with his modern-instrument players and professional chamber choir, but despite his good ear for what we are now used to thinking of as ‘Baroque style’, he can be stiff in places, still reaching for the grace and subtlety of Baroque instruments that made them the logical next step.

RW There was, of course, no ‘definitive’ Messiah even in Handel’s lifetime. Ever pragmatic, he adapted, transposed and radically rewrote numbers according to the singers and orchestral forces available. Sometimes he doubled the violins with up to six oboes. Mackerras followed suit; and from the first bars of the overture the ear is struck by the oboes’ cutting edge. Yet the relatively juicy ECO strings (vibrato was still de rigueur back then) and the stately – yes, stiff – tempo are of their time, as is the jangly sound of the harpsichord. The added trills and twiddles in the overture are a foretaste of things to come. Mackerras sometimes even encourages the choir to add embellishments. Reviewing the CD reissue in Gramophone (12/89), Stanley Sadie called this kind of mass ornamentation ‘clumsy and fairly silly’. We wouldn’t perform it like this today, of course. But the choral and orchestral embellishments often made me smile. Messiah is an act of religious devotion; Mackerras reminds us that it can also be fun.

LK It’s certainly full of life and light. A lot of the solo vocal ornamentation sounds very natural and elegant – not that different from what we might expect today. I’d only question certain places where it sounds more dutiful than expressive. In the da capo of ‘He was despised’, for instance, Janet Baker’s embellishments seem almost jaunty when they could have been shaped in a way to take the despondency to a deeper level. In every other respect she’s wonderful, of course! I enjoyed Elizabeth Harwood’s singing too: such keen radiance and joy in ‘Rejoice greatly’; and if ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth’ is a trifle cold, there’s a real sense of mounting excitement in the recitative section starting at ‘And suddenly there was with the angel’.

RW Yes, I suspect that in concert performances Baker would have been more restrained in her ornamentation – and probably asked for a faster tempo! Her ‘He was despised’ ranks with the slowest on record, and inevitably involves a jolt forwards for the lacerating central section. But I was deeply moved by her burning directness and tonal beauty, and her colouring of key words – ‘despised’, ‘rejected’, ‘grief’.

Harwood, better known in later music, was a lovely soprano, even if her bright tone is a touch more vibrant than we now expect in Handel. Again, the tempo for ‘I know that my redeemer liveth’ seems drawn-out, with no hint of a dance lilt. But Harwood brings an infectious eagerness to ‘Rejoice greatly’, sung in Handel’s original version, as a 12/8 jig – the first time this had been recorded, I think. Another rare variant chosen by Mackerras is Handel’s revised version of ‘How beautiful are the feet’ for duet and chorus, composed for the two male altos in the 1742 premiere, which took place in Dublin. I’d never heard this before, and was captivated. Baker and countertenor Paul Esswood are beautifully matched in their overlapping lines, and there’s a gorgeous moment when the choir takes up the ‘How beautiful’ theme in imitation.

LK For me, Esswood’s singing – liquidly lyrical and with a stylish lilt – is one of the delights of this performance. Still in his mid-twenties and making his professional recording debut, he must have been a pleasant surprise for many listeners at the time. As for the other male singers, Robert Tear hits the mark with a celestial ‘Comfort ye’ and authoritative ‘Ev’ry valley’, while ‘Thy rebuke hath broken his heart’ – which we’re used to hearing as an indignant cry – surprises as a lingering, heartbroken arioso, its downcast mood carrying over into the aria ‘Behold, and see’. But then he should have lifted us off the floor for ‘But thou didst not leave his soul in Hell’ – it’s the turning point of the oratorio!

Raimund Herincx is solid, but for me rather bland in delivery: ‘The trumpet shall sound’ is nine and a half minutes of my life I’d like back, please – though it’s probably the toytown stiff dotting and non-legato of the solo trumpeting that’s mostly to blame. No doubt this interpretation was forged under musicological instruction, but somehow the majesty got forgotten!

RW Nor was I lifted off the floor by ‘But thou didst not see his soul in Hell’, not so much because of the singing but because the continuo – including a busy harpsichord – tends to weigh the music down rather than propel it forwards. I did, though, especially enjoy Tear’s no-holds-barred ‘Thou shalt break them’ – pure theatre, this, in one of the nastiest psalm texts.

As for Herincx, you could never accuse him of subtlety, or of holding back on high notes. His brawny bass-baritone thunders impressively in ‘Why do the nations’. But there’s no sense of mystery in ‘The people that walked in darkness’ – though the fussy harpsichord in the right-hand channel doesn’t help here. And yes, ‘The trumpet shall sound’ is a serious blot on the whole performance: a lumbering tempo, self-conscious dotting from the trumpet and undifferentiated machismo from Herincx. John Shirley-Quirk, on the contemporary Davis recording, is in a different league! But in other respects, not least the choral singing, Mackerras’s Messiah is at least a match for Davis’s. The ‘Hallelujah’ chorus, with the tenors relishing their top Gs and As, is as thrilling as any.

LK Yes, and the last two choruses as well! The Ambrosian Singers are not quite like the professional choirs you tend to get in Handel these days, but all the parts sing with an open-throated, long-lined lust for life that brings presence and a straight-talking urgency to the show. Mackerras controls them superbly: the likes of ‘Glory to God’ and ‘His yoke is easy’ are upliftingly paced, and steady tempos bring dignity to ‘All we like sheep’ and ‘The Lord gave the word’. Most memorably for me, a finely judged balance between weight and momentum makes ‘Surely he hath borne our grief’ a moving via crucis. This is a conductor who knows about using a chorus to make an expressive statement.

RW … an experienced opera conductor, and it shows. The ferocious bite of ‘He trusted in God’ – the nearest Handel came to a turba (crowd) chorus – must have shocked listeners back in 1967. In another challenge to Romantic tradition, ‘Behold the Lamb of God’ becomes an urgent command rather than an awed meditation. At the other end of the spectrum, ‘His yoke is easy’ may be steady by Monteverdi Choir standards, but it’s delightfully crisp and airy, underpinned by happily burbling bassoons – and, as always, Mackerras is a master at building and clinching a climax. Conductors like Sir Malcolm Sargent and, especially, Sir Thomas Beecham had treated Messiah as a series of monumental tableaux. With Mackerras it becomes sacred theatre.

LK Just as it should. Mackerras’s grasp of 18th-century music was dramatic, celebratory, but also clear-eyed and keenly intelligent, and that shows in this performance. So yes, it’s of its time in many ways, but there’s nothing necessarily wrong with that. What’s more important is that you can somehow still hear the freshness in it, even now. I’m happy to have made its acquaintance.

This article originally appeared in the August 2024 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue of the world's leading classical music magazine – subscribe to Gramophone today