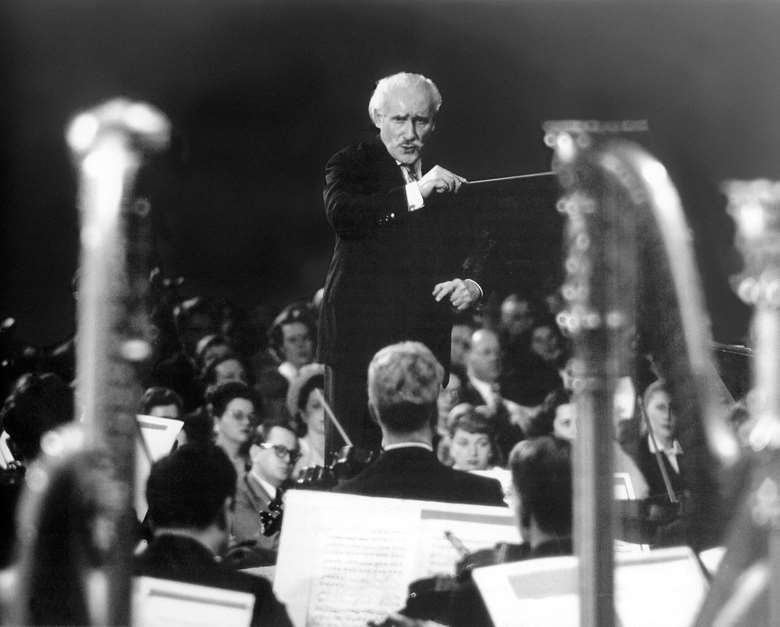

Toscanini's last stand

Mike Ashman

Tuesday, January 3, 2017

The great Toscanini’s final concert with his beloved NBC Symphony Orchestra came dangerously close to disaster. Mike Ashman tells the poignant tale

In a captivating article in the January 2017 issue, Richard Osborne reflects on the tumultuous career of the legendary conductor Arturo Toscanini (subscribe here). To celebrate the latest issue, we present a feature about the conductor's last days extracted from Gramophone's unrivalled digital archive.

‘I was hoping to close this season and be done with it once and for all because I can’t stand being Arturo Toscanini any longer…I would like to rest for what little time remains to me and enjoy a peaceful death.’ In May 1953 Arturo Toscanini was 86 and on the verge of what proved to be his last season with the NBC Symphony Orchestra in New York, a series of broadcast concerts (reduced from the normal 14 to 10) that, if you take his correspondence at face value, was given under duress. ‘Unfortunately,’ he continued to his daughter, ‘my ferocious resistance was beaten by the most ferocious ball-breakers’ – the executives who he said exhorted him to return to the podium.

But, as Toscanini’s biographer Harvey Sachs comments (in The Letters of Arturo Toscanini; Knopf: 2002), ‘it is clear that Toscanini accepted the ‘exhortations’ to conduct another season because this is what he really wanted to do in his heart of hearts’. There was also the question of ‘his’ orchestra. Radio audiences were falling off in the early 1950s, even for Toscanini concerts, and storm clouds were gathering over the future of the orchestra. Sachs believes – from recent research – that David Sarnoff (president of the Radio Corporation of America, which ran the NBC concerts) had kept the orchestra going against the advice of his corporation’s board. Toscanini was well aware that his continuing career and the orchestra’s livelihood were inextricable. It was against this background – and the conductor’s desire to continue making music set against concern about his own abilities – that the 1953/54 season began. Toscanini had wished it to include Bach’s Second Brandenburg Concerto (but his long-serving first trumpet told him he was too old for the tricky high solo part) and two of his big choral favourites – Kodály’s Psalmus hungaricus and (for the last concert) Brahms’s German Requiem – which, in the end, he concluded he was not up to preparing. At the start of the season, also, he had to miss two concerts due to illness. He finally took the rostrum in November for Brahms’s Tragic Overture and Strauss’s Don Quixote. The season continued successfully; many of the performances were later selected for release by RCA (the Strauss tone-poem, the Eroica, the Berlioz Harold in Italy, the Mendelssohn Reformation Symphony and the season’s big project, a complete Un ballo in maschera in two parts). In March 1954 Toscanini conducted his last Beethoven symphony (the Pastoral), a fine performance of Verdi’s Te Deum and an uneven one of Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique (Mortimer Frank in The NBC Years – Amadeus Press: 2002 –says that it ‘sounds like a first run-through of an unfamiliar work by a highly skilled ensemble’; decide for yourself on Music & Arts/Discografico Italiano).

On Toscanini’s desk at the time was a letter of resignation to ‘my very dear David’ (Sarnoff). Prepared by his son Walter, and perhaps others (and in a most un-Toscanini-like style), it announced: ‘And now the sad time has come when I must reluctantly lay aside my baton and say goodbye to my orchestra.’ It took a while before, on his 87th birthday, March 25, the letter was signed and dated. Copies of the letter were, perhaps unwisely, distributed to New York’s musical press at Carnegie Hall on April 4.

After deciding against the Brahms Requiem for this last planned concert, Toscanini opted for a familiar, but lengthy, all-Wagner programme, items that had been consistently successful in his American concerts. Alongside the Lohengrin Act 1 Prelude, the Siegfried ‘Forest Murmurs’, the Götterdämmerung ‘Dawn and Siegfried’s Rhine Journey’ and the Meistersinger Prelude stood originally the Tristan Prelude and Liebestod. For this, just before rehearsals began, the Tannhäuser Overture and Bacchanale, a Toscanini speciality among specialities, was substituted.

Once over some confusion about whether Toscanini was beating two or four in the Lohengrin excerpt, the first rehearsal (there were three altogether) continued until, in the Götterdämmerung music, the conductor decided that the timpanist had come in a bar too early after the offstage horncall at the start of the Rhine Journey. The player incorporated Toscanini’s (erroneous) belief that his entry was after 13 bars and everything then went smoothly – including what critic BH Haggin called a ‘power all there’ run-through of the big 25-minute Tannhäuser excerpt at the second, Friday rehearsal – until the final Saturday afternoon rehearsal. When the timpanist came in correctly according to the score, Toscanini went into a rage; principal cellist Frank Miller advised the player to ‘make it 13 measures’ and, amid cries from the conductor of ‘Shameful! Shameful!’, the passage was repeated. With comments of ‘At last!’ and ‘The last rehearsal’, Toscanini walked off and the rehearsal ended, without the Tannhäuser or the Meistersinger Prelude being played again.

At the concert the next day, Haggin reported in Contemporary Recollections of the Maestro, ‘power was not exercised’ in the Lohengrin, Siegfried and Tannhäuser excerpts. Toscanini, according to members of the orchestra later, had forgotten to beat some changes of time signature in the ‘Forest Murmurs’ but, after the climax of the Bacchanale in the Tannhäuser, he stopped conducting altogether with (and this is an account reported to Haggin by players he knew) ‘his right arm gradually dropping to his side, his left hand covering his eyes’. Guided by some hints from Frank Miller the orchestra continued playing. Toscanini then left the podium, was reminded (by Miller) that he still had Meistersinger to play, beat through that work but left the platform while the orchestra was still playing the final chords.

What radio listeners heard was more dramatic. When Toscanini stopped beating, the two musicians in the radio control room – Samuel Chotzinoff and Guido Cantelli – panicked. First the transmission was taken off the air and there came 14 seconds of silence. Then announcer Ben Grauer spoke of technical difficulties down the line from Carnegie Hall. After more silence, the opening half-minute of a Toscanini recording of Brahms Symphony No 1 (an ironic, but perhaps the only available, choice) was played and then transmission was resumed.

Listening objectively to a CD of the concert as heard in the hall (for example, Music & Arts CD3008) with all that information is hard. It’s also initially seductive because, as in the previous March concert with the Pathétique, the warmth and grace of Toscanini’s orchestra (even under slightly straitened circumstances) can at last be heard in stereo. There is definitely something afoot, a stiffness, a nervousness about the readings. The Tannhäuser still has the wonderful space and warmth (try after 7'30" and 13'10") Toscanini brought to this score and a huge and impressive climax is worked up to around 14'30". After that it feels for a little time almost as if the conductor is observing and listening to rather than leading the performance. Chotzinoff (who was actually there) states in his autobiography that ‘the men stopped playing and the house was engulfed in terrible silence’. We can now hear this is incorrect – there was definitely a faltering, but not a breakdown.

While news of his retirement was announced by NBC, Toscanini dined with family and Guido Cantelli, talking (according to Sachs) of contemporary Italian composers and regretting that he had never conducted Rachmaninov’s Second Symphony. Later he observed: ‘I conducted as if it had been a dream. It almost seemed to me that I wasn’t there.’ Toscanini was back in front of his NBC men once more in June, in lengthy (and apparently sparkling) patch-up sessions for his Ballo and Aida recordings. Although a comeback was discussed – and there were even some casting discussions for a Falstaff at La Piccola Scala to be directed by Luchino Visconti – he conducted no more before his death in January 1957. The orchestra was disbanded, but performed on for a decade as the Symphony of the Air. Their first concert was given with an empty conductor’s rostrum, in tribute to Toscanini.

This article originally appeared in the June 2008 issue of Gramophone. To find out more about subscribing to Gramophone, visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe