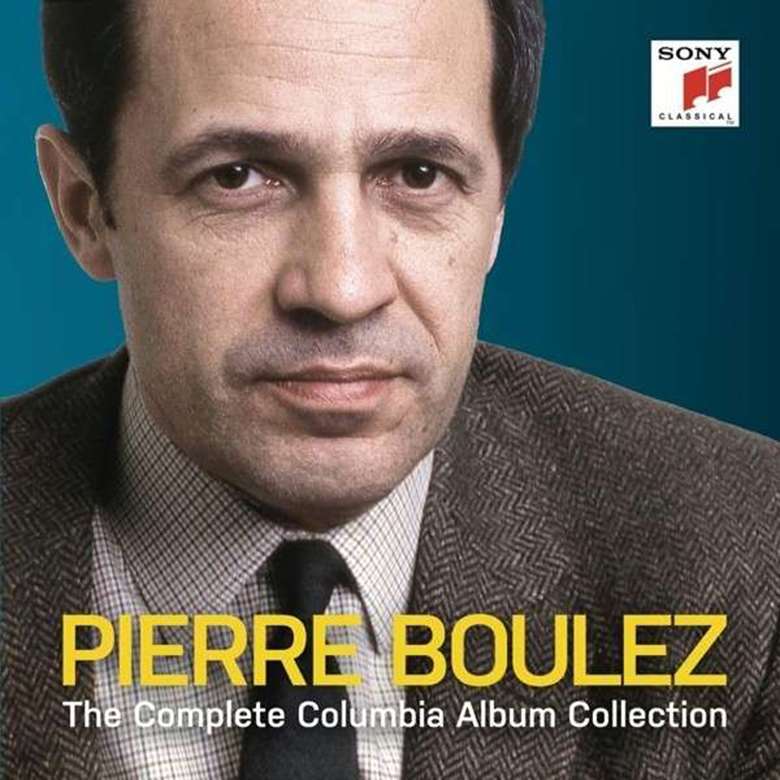

Face-to-face with Pierre Boulez: ‘Acquire and destroy, acquire and destroy, then go further’

Philip Clark

Thursday, March 26, 2015

To celebrate Boulez's 90th birthday, here is Philip Clark's revealing interview with the composer and conductor from 2010

As we’re wrapping up, Pierre Boulez slips in an afterthought: ‘I may be wrong, but I equate music with culture,’ he asserts. ‘I don’t think music is an entertainment product. It’s a product of culture – not for marketing, but to enrich lives. All these years, I’ve been trying to convince people that music is not there to please them; it’s there to disturb them.’ And with that manifesto resonating around Boulez’s office in the Cité de la Musique in Paris, I lean over and switch my digital recorder off. End on a high, I’m thinking. After a verbal joust lasting 90 minutes, Boulez has delivered the money-shot: that one line every journalist hopes their subject will gift them, a pithy précis of their creative credo that – no matter where it occurs in the interview – can be parachuted in as an opening gambit guaranteed to grab the attention. Then small talk. Boulez asks me how I’m spending the evening. I tell him I’m seeing friends who live in Montmartre near, as it happens, the tiny house Erik Satie once inhabited. Boulez nods approval. ‘You still live in Baden-Baden?’ I counter. ‘Oh yes,’ he responds. ‘It’s where I go when I need peace to compose.’ We’re at the lift now and Boulez is concerned I shouldn’t get lost when I reach street-level. I listen and learn: the history of 20th century music is giving me subway directions.

What a history! To his detractors Boulez has ruthlessly imposed his narrow interests upon a largely unwilling and uninterested public. A dictator, a pedant, a puritan; he personifies everything wrong with music in the modern world. But to others, Boulez’s ideas and compositional methods put bombs under lazy, parochial thinking. His polemics – aimed at neo‑classicism and resistant strains thereof, and later turned against Schoenberg himself – have been designed to keep people thinking, guessing, moving on. Music as moral philosophy. He has done more than anybody else to educate and inform us about the music of our time.

When one polemical outburst bit back in the febrile atmosphere of post-September 11, three Swiss policemen raided Boulez’s Basle hotel room to confiscate his passport. Swiss police files had dredged up his notorious comments about wanting to blow up opera houses and profuse apologies were subsequently issued. But I have a fantasy of Boulez patiently explaining the aesthetics of contemporary music-theatre to Inspector Knacker: his vision of an opera where music doesn’t just support text. ‘Both elements must be unified on a more fundamental level,’ he would say. ‘Just like the instruments and electronics in my Répons.’

Boulez, a few weeks short of his 85th birthday, has just completed a three-hour rehearsal of Birtwistle’s …agm… with the Ensemble Intercontemporian, and now it’s my turn to take down his particulars. To celebrate his birthday milestone Deutsche Grammophon is releasing Boulez’s new recordings of Ravel’s piano concertos (featuring Pierre-Laurent Aimard, who also plays Miroirs), his first recording of music by turn-of-the-(last)-century Polish composer Karol Szymanowski (the Symphony No 3 – the Song of the Night – and First Violin Concerto with Christian Tetzlaff), and Mahler’s Des Knaben Wunderhorn (vocal soloists Magdalena Kožená and Christian Gerhaher) paired with the Adagio from the Symphony No 10.

Ravel, Szymanowksi, Mahler. Repertoire plucked from the bedrock that any other conductor in Deutsche Grammophon’s roster might have offered up. Isn’t Szymanowksi an incongruous choice from a man obsessed with Schoenberg, Webern, Varèse and Elliott Carter? Where will it end? Boulez conducts William Walton? Gershwin? And where’s the New Music? Surely it’s more important to illuminate new or undocumented work? But as Sony’s recent 48-CD Boulez Edition reminds us, Boulez always did conduct further outside his natural habitat as a composer than either his supporters – keen to preserve their image of the clean-cut modernist – or his opponents – bent on airbrushing out the full range of his sympathies and interests – would admit. In the past decade, though, Boulez’s embrace of unlikely repertoire has noticeably intensified. Why?

‘I have done my best to find acceptance for the masterpieces of Stravinsky and Schoenberg – especially Schoenberg, Webern too – but there are other worlds to be explored, even if they are less attractive or important,’ Boulez replies. ‘I don’t estimate music in order of importance; simply it is, or isn’t, interesting. Hindemith: music which is very well put together, yes, but that says nothing to me. But Szymanowksi has a striking and unique personality.’

Szymanowski wrote his Third Symphony in 1916; his First Violin Concerto followed a year later. What sources and models does Boulez perceive in these mid-period works? ‘The Third Symphony, in particular, is a bridge between Debussy and Scriabin, but it is better composed than Scriabin, who is repetitive and does not develop his themes. Szymanowski is more astute.’ His material is more fully developed? ‘Exactly. This kind of mysticism you find also in early Stravinsky, like his Zvezdoliki, written just before Sacre. I regret he did not move more in this direction. Instead you have neo-classicism, which is completely uninteresting.’ Stravinsky did indeed return to mystical concerns in late works like the Requiem Canticles and Introitus though? ‘He should have done it sooner!’ Boulez snaps.

So far so good. Thirty minutes in, and Boulez has given neo-classic-think a kicking. But his nuanced ideas about neo-classicism – about the nature of musical material itself – become clearer as we turn to Ravel. ‘The period of Ravel I like most is Miroirs and Gaspard de la nuit [1905/1908],’ he explains. ‘Because afterwards, in the G major Piano Concerto, he wants to be of his time. What you hear is jazz of 1925, so that is immediately dated. But other themes are not dated; it’s Ravel pure. The language he borrows destroys his own language.’

Could Boléro be considered the opposite end of the spectrum from the G major Concerto; pure Ravel reiterated over 15 minutes with a single climactic key-change? Boulez describes it as Ravel’s ‘bet’, proving he could do something outlandish. Then suddenly we’re talking about Schoenberg. ‘Boléro is about Farbenmelodie. Schoenberg did that 15 years earlier and it was less popular, but more important. Ravel’s genius is finding exactly the right colour for a melodic line; but Schoenberg is more complex and difficult to realise. In the third of the Five Orchestral Pieces, one note is played by muted trumpet, then the second violins, then the oboe. To balance that properly is very challenging.’ But in later works, like the Piano Concerto and Variations, Op 31, Schoenberg adopts a more conventional mode of orchestration? ‘Rhythmically and structurally, the Piano Concerto is reminiscent of Stravinsky’s neo-classicism. But Schoenberg at least reshapes the vocabulary. He does not adapt his vocabulary to the past; he adapts the past to his vocabulary.’

I’ve often wondered about when/how/if Schoenberg’s Jewish identity informed his music-making; that essential instability of his harmony, its restless wandering and alienation from mainstream niceties. What does Boulez think? ‘I find nothing Jewish in Schoenberg. Mahler, yes, the way he uses all those sources,’ he cautions. But I press the point. I’m not talking style or idiom, I say, more that the harmony is unsettled, keeps moving. ‘In Wagner too,’ he retorts. Yes, but Wagner’s narrative is essentially tonal. That’s not true of Pierrot lunaire, Der Buch der hängenden Gärten even. ‘In Pierrot, unlike Wagner, the chords are not classified. A classified chord – because it belongs to a class – you recognise immediately; you have an instinctive reaction to it. In Varèse’s Amériques, despite its brutality, chords are repeated and repeated until your perception absorbs them. But the vocabulary constantly changes in Pierrot. There’s no chance for stability.’

Then Boulez pinpoints the precise technical reason why so many people still find Schoenberg impossibly impenetrable. ‘Erwartung uses ostinatos, which gives it stability. In the third of the Five Orchestral Pieces there is simply a chord of five notes – it goes down, goes up and back to its first position. That’s all. Easy. But problems of perception occur when complex harmonic movement is not controlled vertically. That’s when you need to listen differently.’

Problems of perception, and the need to listen differently, are the root cause of Boulez’s tussles with the classical Old Guard: the assumption (or wilful misunderstanding) being that formative Boulez works like Polyphonie X for ensemble (1951), the two-piano Structures (1952) and Le marteau sans maître for voice and ensemble (1954) were a master-plan to usurp centuries of tradition, flat-packing musical expression into 12-tone mathematics and self-generating systems. A tonality-verses-atonality soap opera. Although often lumped together with the other two, Le marteau sans maître is not strictly serial, but applies lessons learnt from serial thinking intuitively. Boulez’s portal to this new freedom was his ‘classic’ piece of so-called ‘integral’ serialism Structures, in which every pitch, timbre, dynamic, duration was harvested from a tone-row. Except that even Structures fails to conform to type: Book 2 was added 10 years later and is a ‘free’ rewrite of Book 1, which itself contains a middle section that departs from integral serial rigour to provide gestural and sonic relief. As we talk Structures, Boulez makes it clear that the work was a one-off experiment in ‘complete anonymity’. He wanted to be jolted into another way of thinking; it freed him from serialism’s relentless ‘one to twelve’. From mathematical control grew new liberties that he explored in Le marteau and the Third Piano Sonata.

Having chanced such extremes himself, what is his take on the trend for neo-tonality in younger French composers like Guillaume Connesson, Richard Dubugnon and Fabien Waksman? Does that disappoint him? Boulez is blunt: ‘They are wasting their time. There are always people who will take an easy intellectual path. Poulenc coming after Sacre? It was not progress. I cannot polemicise with these people – they don’t exist, simply that.’

But radical musical agendas, fuelled by tonality, have indeed taken flight since The Rite of Spring. And I don’t mean Poulenc or Hindemith or Stravinsky’s later neo-classicism – I’m thinking the likes of Ives, Tippett, Finnissy, Sciarrino, Lachenmann, Anthony Braxton, Lou Harrison. All, with their radically different agendas and points of departure, stripping tonality down, collapsing the functionality of tonality into itself, viewing tonality in a spectrum that might also embrace atonality and noise, creating music with tonal associations that fundamentally alters context and plays with our expectations. Could Boulez see his way to accepting anything like that now?

‘Not really. Aaron Copland wrote rhythmically and harmonically complex pieces early on, like the Piano Variations. Then folklore and dance. That’s very nice, but…’ – Boulez runs out of words and shrugs – ‘Ives was, at least, an original. His music presents a paradox: to perform his orchestral music, which I did when I was with the New York Philharmonic, you have to rewrite it, but that means diluting what makes it initially interesting. Ives is attempting to grasp things he can’t grasp. It is unachieved.

‘The Des Knaben Wunderhorn settings of Mahler I have just recorded are interesting to compare to Ives. Mahler uses practically the same sources: military marches, folk and dance music. But Mahler has organised this material. In Ives, though, everything is presented at the same level, juxtapositions of things which would otherwise be independent. There is no construction.’

Our discussion of Ives then segues, instinctively, towards John Cage and Morton Feldman, composers who Boulez tars with that same brush. ‘I met them when I went to New York in 1952, and I found they were not eager to acquire knowledge. They were already gods, they thought, and God is never wrong. If you are “right”, you never acquire anything. Acquire and destroy, acquire and destroy, then go further. That’s what composers should do. I don’t see this type of evolution in Feldman or Cage.’

But those of us who value Ives, Cage and Feldman do so precisely because they didn’t re-apply European methodologies and ideologies to their uniquely American situation. Their rebellion – the freedoms they sought – were distinct from Boulez’s. When classical boffins haughtily dismiss Cage as a buffoon, mocking his work as a grand joke played out at the expense of Western tradition, they fail to reap the rewards of his penetrating critiques. But no one could try that on with Boulez. His intellect, imagination, the depth of his musicianship and, of course, those famously precision ears insure against that.

Cage defined himself as an anarchist and largely x-ed himself out of the classical slipstream. But Boulez tackles the problem of tradition head-on, insisting that the most traditional thing about tradition is the inner dynamic of its radicalism; its relentless evolution towards now. Composers who, in the name of tradition, freeload off the hard-earned expressive language of their forefathers distort tradition. As Boulez tells me, ‘the more you are adventurous, the more you must be critical’. But Boulez has kept the faith, and remains the conscience of Western tradition. Like all Popes, of course, there have been hopelessly weak disciples and times when purist doctrine has obscured other worthwhile gospels (apropos Cage and Feldman). So it’s no surprise that Boulez’s Big Church finds room for Ravel, Szymanowksi and Mahler, alongside progressive, thoughtful New Music. Post-modern sinners at the money temple? Repent, for tomorrow is now.

In the current (April) issue of Gramophone, David Robertson pays a 90th birthday tribute to Pierre Boulez, his colleague and friend.