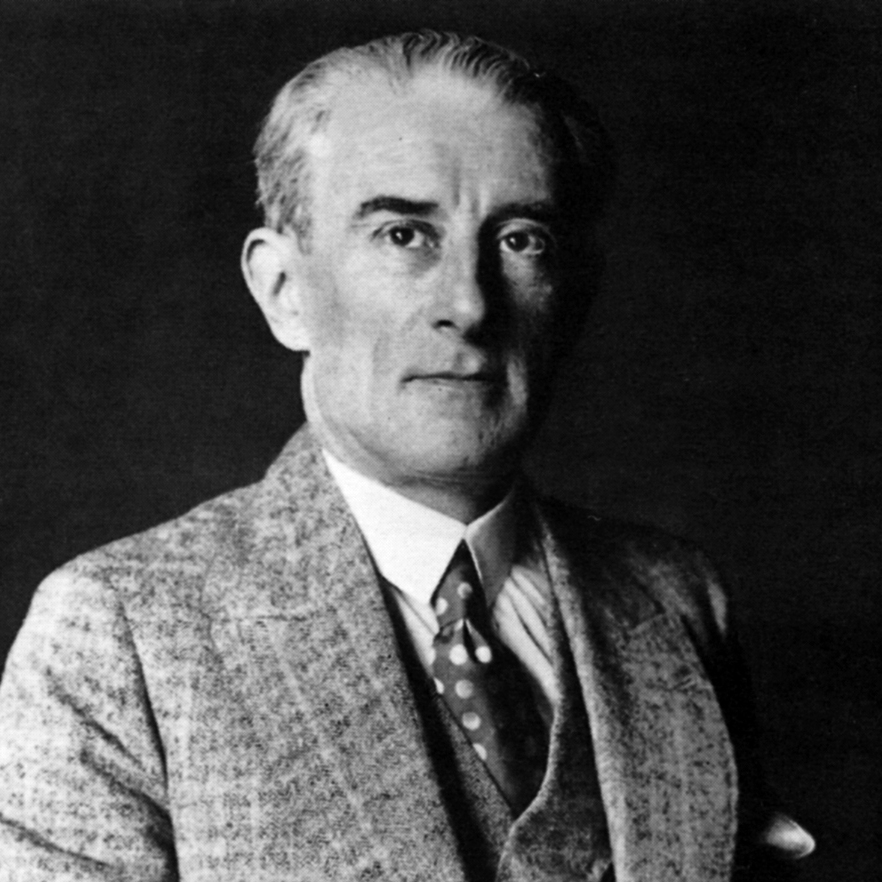

Ravel

Born: 1875

Died: 1937

Maurice Ravel

Ravel’s greatest significance was in establishing, with Debussy, a distinct French school of music, ridding it of Wagnerian influence. One of the greatest orchestrators in musical history, he put it to use in music ranging from delicate impressionistic pictures to fantasies portraying children and animals.

Explore Ravel's life and music...

Top 20 Ravel recordings

From Boléro to Daphnis et Chloé, here are Maurice Ravel's greatest works in outstanding recordings... Read more

Ravel's Boléro – which recording should you buy?

Boléro has attracted interpreters ranging from Pierre Boulez to James Last. Philip Clark seeks out the finest moments of an 80-year recording history... Read more

Ravel Piano Concerto in G, by Pierre-Laurent Aimard

The Frenchman admires this showpiece – but being French isn’t a prerequisite for playing Ravel... Read more

Obituary: Maurice Ravel (March 7, 1875 - December 28, 1937)

The original Gramophone obituary from February 1938, by Martin Cooper... Read more

Ravel’s family moved to Paris when Maurice was three months old and his talent was encouraged. His music lessons began in 1882 when he was seven; in 1889 he entered the Paris Conservatoire, where Fauré was among his teachers, and he remained a student for a further 16 years, an unusually long time. One reason for this was his strenuous attempts to win the coveted Prix de Rome, which Berlioz, Bizet and Debussy before him had won. He was placed second in 1901, tried and failed in 1902 and 1903, and then was eliminated, humiliatingly, in 1905 before the final stage of the competition. But by this time he was already established as a respected composer: the lovely Pavane pour une infante défunte, his piano piece Jeux d’eau, his String Quartet and the three songs with orchestra called Shéhérazade had been well received. The jury’s decision became a cause célèbre, amid charges of favouritism, and it led to the resignation of the director of the Conservatoire, Théodore Dubois (Fauré took his place). When the scandal had died down, Ravel was famous. Over the next decade or so, he wrote some of his finest work (Rapsodie espagnole, Gaspard de la nuit, Daphnis et Chloé).

The First World War had a decisive and ultimately fatal effect on Ravel: he volunteered his services for the army and the air force but neither could use him because of his very light weight (about seven stones) and frail physique. Instead he became an ambulance driver at the front in Verdun. Although short in stature (a little over five feet) and sensitive by nature, his health up to that time had been good. However, the war broke him physically and emotionally. After being released from his driving duties with dysentery, he was compelled to recuperate in hospital. His mother’s death followed closely afterwards, deeply affecting him, and he began to suffer from insomnia and what he called ‘nervous debility’. Thereafter, despite producing a number of masterpieces, inspiration came less frequently. Nevertheless, his career continued smoothly.

Ravel never married. Soon after the war he moved to a small villa called Belvédère about 30 miles to the south-west of Paris in Montfort-l’Amaury, living in semi-seclusion. All his affection was lavished on his beautiful home which, according to his biographer Madeleine Goss, ‘became his mother, wife and children...the only real expression of his entire life’. There he lived with his housekeeper, a collection of mechanical and clockwork toys and a family of Siamese cats (a passion he shared with Debussy). He accepted few pupils but gave friendly advice to many (including Vaughan Williams); he never taught in any conservatory. In fact Ravel comes across as an isolated, reserved and coolly aloof individual, ‘more courteous than cordial…and more ingenuous than anything else,’ as his lifelong friend Roland-Manuel put it. After Debussy’s death in 1918 he was hailed as France’s greatest living composer and honours were heaped upon him, though (perhaps in retaliation for the Prix de Rome debâcle) he vehemently turned down the Légion d’honneur in 1920. Invitations poured in for him to conduct his music all over Europe (in this and as a piano soloist he was only adequate, and then only in his own works).

In the autumn of 1932 he had a road accident in a Paris taxi from which he never fully recovered. Gradually, his memory went. Eventually, suspecting a brain tumour, an operation was decided upon. No tumour was found. Nine days later, having briefly regained consciousness and calling for his brother, Ravel passed away. Shortly before, he had heard a performance of his own Daphnis et Chloé and is reported to have said, in tears, ‘I still have so much music in my head. I have said nothing. I have so much more to say.’

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.