Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition (orch Ravel): a guide to the best recordings

Mark Pullinger

Wednesday, September 20, 2023

Ravel’s vivid orchestration of Mussorgsky’s gallery has long eclipsed the piano original in popularity. Mark Pullinger ranges across 10 decades in his search for the finest recording

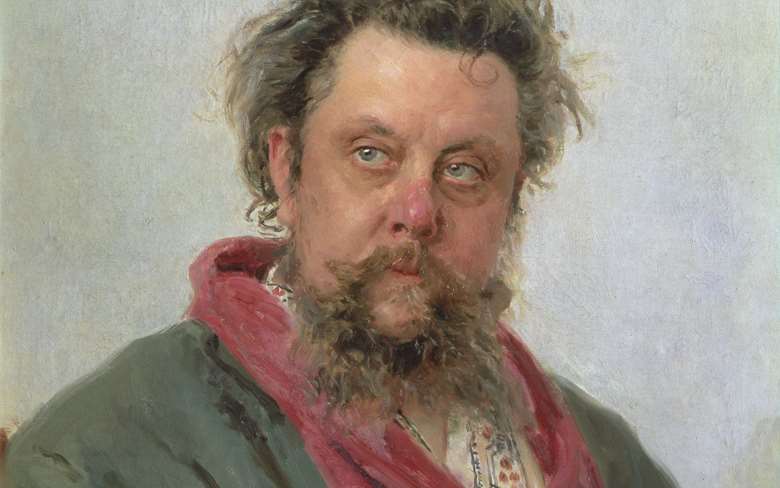

The 1881 portrait of Modest Mussorgsky by Ilya Repin depicts him as unkempt, tousle-haired, bleary-eyed and red-nosed. It was painted in a St Petersburg military hospital where the alcoholic composer was ‘drying out’. There was no space for Repin to use an easel so he had to perch at a desk near the armchair where his subject was seated. Mussorgsky was only 42 years old. Before the final sitting, he was dead.

It’s ironic that Repin’s portrait is far better known than any of the works by Mussorgsky’s dear friend Viktor Hartmann, which were the inspiration for his 1874 piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition. It’s a portrait that desolately stares out at us on countless LP and CD covers.

A Hartmann tribute

Hartmann was even younger than Mussorgsky when he died of an aneurysm in 1873, aged only 39. His death distressed Mussorgsky deeply. ‘My dear friend, what a terrible blow!’ he wrote to the critic Vladimir Stasov. ‘Why should a dog, a horse, a rat, live on and creatures like Hartmann must die!’

The following spring, around 400 of Hartmann’s works – oil paintings, watercolours, pencil sketches, designs – were displayed in a memorial exhibition at the St Petersburg Society of Architects. Mussorgsky lent drawings from his own collection and resolved to write a descriptive piano suite – black-and-white reproductions, if you will – inspired by 10 of Hartmann’s works. He laboured feverishly. In June 1874 he wrote to Stasov: ‘Hartmann is boiling as Boris [Godunov] boiled: the air is thick with its sounds and its ideas. I’m devouring it all, gorging on it, and I barely have time to scribble them on paper.’

‘My physiognomy,’ he explained, ‘can be seen in the intermezzi.’ These are the short promenades that link several pictures, a ‘framing device’ (pun intended) as if Mussorgsky were sauntering from one painting to the next. Marked nel modo russico (‘in the Russian manner’), it is an ungainly theme, alternating 5/4 and 6/4 metres, ‘an awkward, waddly rhythm’, wrote Alfred Frankenstein, adding pithily, ‘Mussorgsky was no sylph’.

Enter Maurice Ravel

Few people paid much attention to Pictures until the émigré Russian conductor Serge Koussevitzky commissioned Maurice Ravel to make an orchestration nearly 50 years later. Mikhail Tushmalov, a pupil of Rimsky-Korsakov, made the first orchestration (1891) but it omits several pictures and promenades. Henry Wood orchestrated Pictures in 1915 – it was programmed three times in that year’s Proms season, including the Last Night – but he withdrew it when the new version appeared, in deference to Ravel’s masterly work.

And it is masterly. Ravel had orchestrated Mussorgsky before, assisting Igor Stravinsky on parts of Khovanshchina at Serge Diaghilev’s request in 1913, so he was already deeply immersed in Mussorgsky’s style. Arturo Toscanini regarded Ravel’s version as a genuine treatise on orchestration, on a par with Berlioz’s. ‘Mussorgsky’s alleged incorrections are sheer strokes of genius,’ Ravel said in a 1929 interview, ‘very different from the blunders of a writer lacking linguistic sense or of a composer lacking harmonic sense.’

How ironic that Ravel turned out to have been working from an edition of the piano score edited by Rimsky! Little harm was done, though; the only significant differences are Ravel’s pianissimo start to ‘Bydło’ (Mussorgsky had the ox-cart enter fortissimo), plus the final cadence of ‘Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuÿle’, which Rimsky had ‘corrected’ to C-D flat-C-B flat from Mussorgsky’s more angular C-D flat-B flat-B flat (Toscanini restores Mussorgsky’s intentions here, as does Lorin Maazel in his two recordings).

Serge Koussevitzky

On October 19, 1922, Serge Koussevitzky conducted the premiere at the Paris Opéra. He held exclusivity rights over Ravel’s orchestration for six years, so it’s no surprise that he also made the first recording, with the Boston Symphony in 1930.

That 1930 recording has its limitations. The tea-tray percussion is recessed, the alto saxophone in ‘The Old Castle’ is woolly and the solo trumpet for Schmuÿle sounds anaemic. Koussevitzky’s opening Promenade lurches in tempo, as does the closing ‘Great Gate of Kiev’, but it’s fascinating to hear how quickly ‘Bydło’ is taken.

Your gallery guide

Other orchestrations followed, but Ravel’s version has remained the predominant one – both in the concert hall and on disc – and it is the sole consideration in this Collection. The only significant challenger is Leopold Stokowski’s 1939 version, painted in gaudy colours. Stokowski omitted ‘Tuileries’ and ‘Limoges’, finding them too Frenchified. Try Stokowski’s Decca Phase 4 account (9/66) and, for plushly upholstered modern sound, Oliver Knussen’s Stokowski tribute with the Cleveland Orchestra (DG, 10/04). A special nod goes to the indefatigable Leonard Slatkin, whose recording with the Nashville Symphony (Naxos) dips into 15 different orchestrations. Slatkin has also recorded Ravel’s (twice) and will feature on our tour.

Rather than a chronological survey of the 80+ recordings I listened to, allow me to be your gallery guide as we wander through the exhibition Mussorgsky and Ravel co-curated, picking out the points of interest along the way. Audio headsets at the ready…

Promenades

The first Promenade immediately throws the spotlight on to the solo trumpet. Step forwards Adolph ‘Bud’ Herseth, fearless principal trumpet of the Chicago Symphony for an astonishing 53 years (1948-2001), who features on six Chicago Pictures, nailing his opening salvo every single time. Herseth is bright and breezy for Rafael Kubelík, the very first Mercury Living Presence recording in 1951, but is more sober for the stern Fritz Reiner in 1957. My favourite solo comes courtesy of the Philadelphia Orchestra’s Gilbert Johnson for Eugene Ormandy in 1966, a bold swagger that establishes a sense of anticipation for what’s to follow.

Fritz Reiner’s 1957 account with the Chicago SO has stood the test of time (photo: Archive PL/Alamy Stock Photo)

By the time Riccardo Muti recorded it in 1978, the Philadelphia’s rapier-like principal was Frank Kaderabek, terrifically exciting. Susan Slaughter, the first female principal trumpet in a major orchestra, is jaunty, with a darker tone, for Leonard Slatkin and the St Louis Symphony in 1975. Turning away from America, enjoy the abrasive blare of the Soviet trumpet in Evgeny Svetlanov’s USSR State Symphony Orchestra in 1974, followed by weighty strings as a portly Mussorgsky enters the gallery.

The other Promenades are reflective or purposeful. The fourth offers a little tease, a cheeky chirrup as Mussorgsky spies the ‘Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks’ out of the corner of his eye and turns to view it. There’s a fifth Promenade, just before ‘Limoges’, that Ravel omits; in his Orchestre National de Lyon account, Slatkin provides his own orchestration, a brass chorale, ending with a long-held trumpet note.

Gnomus

Our first stop is ‘Gnomus’, Hartmann’s design for a toy nutcracker, ‘a fantastic lame figure on crooked little legs’ according to Stasov (one of five pictures that have not survived). Mussorgsky paints a malevolent figure, and with the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1967 Zubin Mehta is a knockout, lower strings scrambling fiercely with plenty of bite. Kubelík is under-the-bed scary, while Muti’s queasy glissandos are particularly telling. The National Symphony Orchestra of Ukraine in 2001 play with character for Theodore Kuchar, their bass clarinet slithering sinuously.

Riccardo Muti’s recording with the Philadelpia Orchestra grabs you by the ears (photo: Lelli & Masotti EMI Classics/Various)

Strangely, some of the tamest gnomes are to be found among Berlin Philharmonic readings: Herbert von Karajan (twice, in 1966 and again two decades on), Claudio Abbado, Simon Rattle and an especially toothless portrayal from Carlo Maria Giulini – a gummy nutcracker that would scare nobody.

Il vecchio castello

‘Il vecchio castello’ (‘The Old Castle’) was a watercolour of an Italian medieval castle in front of which Hartmann painted the tiny figure of a troubadour with a lute, which Mussorgsky depicts in a lilting serenade. In a stroke of genius, Ravel gives the solo line to an alto saxophone, a distinctly non-medieval instrument. Reiner’s troubadour is raunchy, as is Riccardo Chailly’s with the Concertgebouw (1986), who adds a sexy glissando at the end. Muti and Mehta surge along swiftly and Lan Shui’s Singapore Symphony in 2018 has a stylish soloist. Ravel requests the saxophonist to play with vibrato but Slatkin’s in St Louis takes this to blowsy excess.

Leonard Slatkin has recorded Ravel’s orchestration twice, in 1975 and 2012 (photo: Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo)

Slow tempo is a danger here, risking dragging the whole performance early on. Valery Gergiev, with both the Vienna Philharmonic and Mariinsky orchestras, is lethargic, while Svetlanov’s troubadour is arthritic. Another danger is placing the saxophonist too distantly; Karajan’s earlier Berlin minstrel is in the next post code.

Tuileries

In the Parisian garden, children squabble in their play. Gergiev’s Mariinsky woodwinds taunt each other mercilessly, while the central section has them coyly hiding behind their governess’s skirts. Kuchar’s woodwinds are similarly animated, while in 2011 Kirill Karabits builds little crescendos with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra as the arguments grow. Kubelík and Reiner’s Chicago oboe is naggingly acidic. Some children, though, are just too well behaved, notably the period-instrument woodwinds of Les Siècles under François‑Xavier Roth in 2019.

Bydło

‘Bydło’ is a Polish word meaning ‘cattle’. Ravel gives the sonorous melody to the tuba but alters Mussorgsky’s watercolour dramatically, introducing a long crescendo to represent the ox-drawn cart trundling in from the distance before rumbling off again. It is marked Sempre moderato, pesante in the score, so we’re not looking at anything too slow and heavy – it’s oxen pulling a cart, not an armoured tank. Svetlanov is especially guilty here and his Soviet tuba is fuzzily recorded. At the other extreme, Artur Rodziński’s 1945 New York Phil ox-cart is a breathless sprint, surely too fast, as is Ormandy’s express.

Mehta has a fabulous tuba and emphatic timpani to power it along. Kuchar builds his crescendo inexorably, accompanied by a vivid snare-drum rattle. Lorin Maazel paces ‘Bydło’ well in both his recordings; his later one, with the Cleveland Orchestra in 1978, was an early demonstration disc that showcased Telarc’s outstanding engineering and it still sounds spectacular today.

Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks

Mussorgsky’s scherzo represents Hartmann’s costume designs for Yuli Gerber’s ballet Trilby, choreographed by Marius Petipa at the Bolshoi in 1871. This is a picture to raise a smile and – surprisingly – the usually dour Gergiev does just that in his recordings. His Viennese chicks twitter merrily, while his St Petersburg ones totter around hilariously, a sense of clockwork running out of control. Samuel Friedmann’s Russian Philharmonic chicks (1996) are very animated, as are Kuchar’s, which skitter about in their shells, crashing into each other. Antal Dorati’s Minneapolis woodwinds raise a chirpy smile but the 1959 Mercury recording is dry and airless.

Pristine but humourless: Arturo Toscanini’s chicks are tightly disciplined, Philippe Jordan’s too metronomic and Dmitry Kitaenko with the Gürzenich merely paints a dainty dance, a lacquered Fabergé egg that completely misses the comedy.

Samuel Goldenberg & Schmuÿle

These two pencil sketches were owned by Mussorgsky himself. They depict two Jews in a Polish ghetto in Sandomierz – a rich man (Samuel Goldenberg) in a fur cap and a beggar (Schmuÿle) who is trying to wheedle money out of him. Are they two aspects of the same person? Schmuÿle is Yiddish for Samuel, so these unkind caricatures could be a double-sided portrait. Ravel dresses Goldenberg in expensive strings and woodwinds, then Schmuÿle stammers on solo trumpet, another virtuoso brass moment. Svetlanov and Mariss Jansons (2008) add unwritten percussion when the portraits overlap.

Slatkin in St Louis is terrific here, animated strings sharply accented before Slaughter’s incisive trumpet. In Chicago, Kubelík’s strings are as angry as a nest of wasps, while Reiner draws clipped, haughty phrases. Muti’s strings are angular and his trumpet pierces. George Szell’s Cleveland trumpet nags relentlessly in 1963; Chailly’s trembles and brays, although is too distantly placed.

Limoges, the marketplace

Hartmann’s drawing was of a cathedral facade, but Mussorgsky homes in on the market scene in the foreground and even wrote an imaginary gossipy conversation. Gergiev is excellent, Viennese and Russian housewives prattling urgently, while sparks fly with Muti and Reiner. Abbado’s London Symphony Orchestra woodwinds exchange elegant banter, while Les Siècles are garrulous and gallic, Roth’s band at their best. Svetlanov pinpoints piquant details – clarinet squeals, harrumphing horns – and as the scandalous chatter grows, brass and tam-tam practically explode into…

Catacombs and Cum mortuis

In a gloomy drawing, Hartmann and fellow architect Vasily Kenel examine a pile of skulls in the Paris catacombs, a guide holding a lantern. Mussorgsky then segues into ‘Cum mortuis in lingua mortua (With the dead in a dead language)’, which is not a picture but the composer’s sombre reflections on mortality.

The Classic Choice: Chicago SO / Rafael Kubelík

The Chicago brass excel here, especially for Reiner and Kubelík, as do the Philadelphia for Ormandy and Muti. Lan Shui’s Singapore Symphony brass are beautifully blended, almost sounding like an organ. Russian brass are more pungent: Svetlanov’s have a paint-stripping rasp, while Gergiev’s Mariinsky glower and snarl, the woodwinds’ underworld reflections eerily sketched.

The Hut on Hen’s Legs (Baba-Yaga)

Hartmann’s design was for a clock, but Mussorgsky lets his imagination run riot and releases the bone-crunching witch for a wild ride, grinding her pestle and mortar across the skies. It’s difficult to go wrong here – sock the listener with percussive welly and make the central section (where Ravel doubles tuba and harp!) creepy without letting the tension sag.

A Great Gate in Kyiv: Nat SO of Ukraine / Theodore Kuchar

Muti pounds hell-for-leather and the slithering Philadelphia woodwinds chill, as does the bony xylophone. Karabits is fast and whippy and there’s a mighty shudder as Mehta’s witch gets airborne. Kuchar has a demonic bass drum and in the quieter sections you can hear the clatter of keys as the woodwinds tremble. Singapore double basses give percussive snaps. St Louis features scrabbling contrabassoon, fierce brass and an excellent tam-tam.

The Great Gate of Kiev

Featuring a great dome like a Slavic warrior’s helmet, this was Hartmann’s entry into a competition to design a stone gate honouring Tsar Alexander II’s escape from assassination when he visited Kyiv in 1866. It was never built – only in Mussorgsky’s epic score, which crowns his suite regally. In Ravel’s orchestration it has unmistakable echoes of the Coronation scene from Boris Godunov, while the central episodes quote the Orthodox hymn As you are baptised in Christ. The Promenade theme reappears so that this noisy finale is also a self-portrait of Mussorgsky himself, red-nosed, a little out of breath.

In Chicago, Reiner has great brass and percussion, while I love the monastic woodwind chants for Kubelík, who sprints through his finale. Karajan’s ‘Great Gate’ is marmoreal and solemn (at 6’44” it would have been quicker to build Hartmann’s design!). With the Mariinsky, Gergiev indulges in full Boris Godunov regalia but without Karajan’s torpor.

Mehta’s percussion glitters and shimmers. Ormandy maintains a sense of propulsion rather than pomp, and he allows his bell to resonate after the orchestral cut-off. Kuchar takes a brisk view, but it’s just as triumphant … and who can resist a ‘Great Gate’ recorded in Kyiv itself?

Gallery gongs: favourite discs

Surveying Mussorgsky’s gallery across many recordings, a few things become clear. First, American orchestras have made some pretty damn fine recordings of Pictures, often with state-of-the-art engineering for their respective eras, and many of them have stood the test of time. Mehta, Reiner, Ormandy and Slatkin are unlucky to miss a podium place.

At his best, Gergiev can be thrilling, both with the Vienna Phil and, especially, his Mariinsky Orchestra, an earthy account painted in dark hues and rich oils. There are two earlier Gergiev discs, both from 1989: a live one on Russian Legacy when the Mariinsky was still called the Kirov (and St Petersburg was Leningrad), and a studio one with the London Philharmonic (9/90), his first recording for Philips (the conductor clean-shaven and with a baton instead of a toothpick). The LPO one is very fine but has never, to my knowledge, been reissued.

Soaked in vodka: Mariinsky Orch / Valery Gergiev

Of the classic recordings, there’s something rather special about Kubelík, the Mercury Living Presence recording that made Alec Robertson ‘sit bolt upright with amazement’ (10/52). It shows its age in places now but the interpretation is so hellishly exciting that I can forgive its limitations.

In several Gramophone reviews over the years I’ve championed Kuchar’s splendid Kyiv recording, so my recommending it here is no sympathy vote in recognition of the horrific situation in war-torn Ukraine, but based on its outstanding musical virtues.

Top Choice: Philadelphia Orch / Riccardo Muti

With streaming and playlists, you can mix and match your ideal digital Pictures at an Exhibition, but for a single recommendation, the palm goes to Riccardo Muti in Philadelphia. This recording emerged in my top five choices in nine of the 10 pictures – only the ‘Unhatched Chicks’ lack the last ounce of humour. Robert Layton gave this record an ecstatic review when it first appeared in Gramophone’s pages in April 1979: ‘Muti’s reading is second to none and the orchestral playing is altogether breathtaking.’ It’s impossible to disagree.

This article originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue – subscribe today