Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute): a guide to the best recordings

Wednesday, April 19, 2023

The Magic Flute was a welcome operatic success for Mozart during his hectic final year. Richard Wigmore considers ten decades of recordings of this enchanting masterpiece

Friday at half past 10

at Night

dearest best little wife! –

I’ve just got back from the Opera – It was as full as ever – the Duetto Mann und Weib etc and the glockenspiel in the first act were encored, as usual – also the Boys’ trio in the 2nd act – but what pleases me most is the silent approval …

Mozart’s letter to his wife Constanze of October 7, 1791, gives us the earliest report on Die Zauberflöte, advertised to the Viennese public as ‘a comedy with machines’. Notching up nearly 100 performances within a year, the opera was the triumph the actor-manager Emanuel Schikaneder had hoped for at his suburban Freihaus-Theater auf der Wieden. If Mozart had lived beyond the end of the year, Die Zauberflöte would have transformed his fortunes.

From the outset the libretto was derided as an inchoate farrago. Its merits and meaning are still debated. Inconsistencies abound.

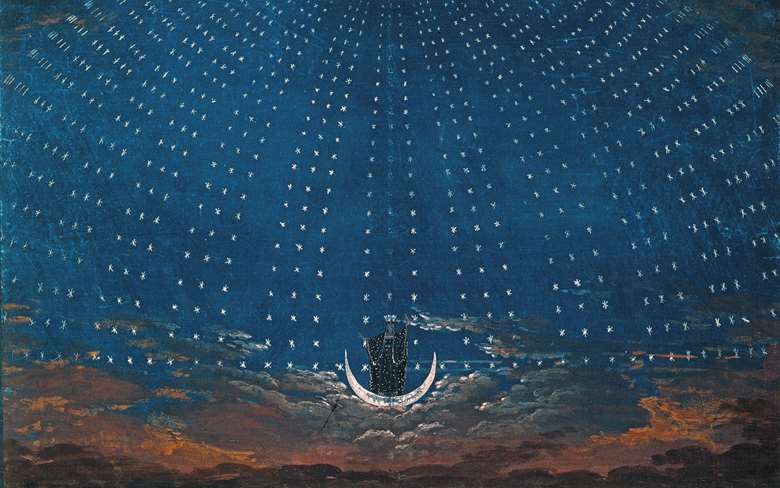

‘Magic’ operas, guaranteeing exotic settings and lavish use of ‘machines’, had already proved crowd-pleasers at Schikaneder’s Freihaus-Theater. Paul Wranitzky’s Oberon, König der Elfen (‘Oberon, King of the Elves’) had set the trend in 1789. A year later Mozart may have contributed to Der Stein der Weisen (‘The Philosopher’s Stone’), a collaborative effort between Schikaneder, Benedikt Schack, the first Tamino in Die Zauberflöte, and Franz Gerl, the first Sarastro. Quick to spot a potential winner, the convivial Schikaneder teamed up with his old friend Mozart to concoct a ‘magic’ libretto that drew on Viennese pantomime, Christoph Martin Wieland’s fairy-tale collection Dschinnistan, the Masonic novel Sethos by the Abbé Jean Terrasson and the essay The Mysteries of the Egyptians by Ignaz von Born, Vienna’s leading Freemason until he withdrew from the Craft in 1786. Schikaneder, whose roles included Hamlet and Lear, knew his Shakespeare and there are self-evident parallels between Die Zauberflöte and The Tempest: Sarastro as Prospero, the ingénus Tamino and Pamina as Ferdinand and Miranda, the comically villainous Monostatos as Caliban, the Three Boys as Ariel.

See also:

- The 50 best Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart recordings

- Mozart: the Gramophone Award-winning recordings

- Podcast: Exploring Mozart with Richard Wigmore

From the outset the libretto was derided as an inchoate farrago. Its merits and meaning are still debated. Inconsistencies abound. How come the godlike paragon Sarastro employs the blackmailing rapist Monostatos? Sarastro himself seems to have abducted Pamina for his own amorous purposes, and initially, at least, comes over as an unreconstructed misogynist. Why does the malign Queen of the Night send the Three Boys, benevolent spirits of the air, to guide Tamino? Best not to question the logic of fairy tale. What is undeniable is that through the charm and expressive power of his music, Mozart raised the popular genre of the Viennese Singspiel to a level hitherto unglimpsed, and never attained since.

Stylistically Die Zauberflöte is the most heterogeneous opera in existence. Yet Mozart’s protean range, underpinned by a virtuoso technique, ensures that everything hangs together. The Overture’s solemn opening immediately establishes the Masonic framework with its three ritualistic chords (the number three – three boys, three ladies, three temples and so on – is omnipresent). The Allegro then brilliantly fuses the popular and ‘learned’ styles by subjecting its chattering, Papagenoish main theme to fugal treatment. There is more contrapuntal virtuosity in the scene for the Two Armed Men. Who else would have thought of incorporating ostentatious displays of counterpoint into a popular entertainment?

Schikaneder ‑ librettist, and the first Papageno (photography: Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images)

Among the cast, Schikaneder himself took the part of the birdcatcher Papageno, a reincarnation of the Hanswurst figure of Viennese pantomime. His antics regularly stole the show, exactly as planned. Careers began and ended earlier in those days, and most of the singers were in their twenties or early thirties. Even the bass Franz Gerl, who sang Sarastro, was only 26. (Gerl’s wife Barbara played Papagena.) The Pamina, Anna Gottlieb, who in 1786, aged 12, had sung Barbarina in Figaro, was now a seasoned pro of 17. The triumph of youth and young love is a recurrent leitmotif of Mozart’s operas, from Idomeneo, through Die Entführung and Figaro, to Die Zauberflöte. Young or at least youthful-sounding voices are a priceless asset in any performance.

So, too, is a measure of wondering innocence, a quality that seems to have seeped out of Die Zauberflöte during the early 19th century, when it was routinely reordered, parodied and bowdlerised. That lost innocence was also a product of inflated textures and drawn-out tempos. Fragmentary evidence suggests that Mozart liked flowing speeds, and that after his death two numbers in particular, Pamina’s lament ‘Ach ich fühl’s’ and the Act 2 trio ‘Soll ich dich Teurer nicht mehr sehn?’, were performed far too slowly. Slowness and solemnity likewise rule in the recordings from four conductors born in the 19th century – Thomas Beecham, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Otto Klemperer and Karl Böhm. Beecham and Klemperer also take the opera out of the sphere of Singspiel by omitting all the spoken dialogue.

There are, of course, cherishable performances in these sets, especially the Klemperer. As Papageno, Walter Berry displays a lively, unexaggerated comic sense and well-nourished bass-baritone. Nicolai Gedda is a convincing if slightly effortful Tamino, Gottlob Frick a gravelly Sarastro, challenged by Klemperer’s funereal tempo in the hymn ‘O Isis und Osiris’. As Pamina the young Gundula Janowitz sings with luminous, instrumental purity, almost vindicating the conductor’s plodding six (or is it 12?) in a bar for ‘Ach ich fühl’s’. But the real star here is the even younger Lucia Popp, the most compelling and – yes – sensuous Queen of the Night on disc. Too many sopranos in this high-wire role are either shriekers or soubrettish squeakers. Popp, her voice all of a piece, is pinpoint accurate, venomous without forcing in her famous ‘revenge’ aria ‘Der Hölle Rache’, always thrilling as sheer sound.

I can’t share the enthusiasm of some past and present Gramophone colleagues for the pre-war Thomas Beecham recording, despite Gerhard Hüsch’s direct, bright-eyed Papageno and some good things from Helge Roswaenge as Tamino and Tiana Lemnitz, a rather mature, knowing Pamina. ‘Not this conductor’s piece’ was my summary after two hearings of Wilhelm Furtwängler’s poorly recorded 1949 live Salzburg performance, complete with stage clatter, and his 1951 EMI recording (1/96). In both Irmgard Seefried’s gentle, flutey Pamina is touching. But what some might hear as spiritual profundity strikes me as simply ponderous.

Fifteen years later Karl Böhm drew sumptuous sonorities from the Berlin Philharmonic. His tempos, though, are barely more mobile than Klemperer’s or Furtwängler’s; and there’s an absurd mismatch between the singers and the actors who speak their dialogue. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, never an obvious child of nature, sings a thinking man’s Papageno. The women too often sound strained. As the Armed Men, James King and Martti Talvela, masquerading as Siegfried and Fafner, eclipse all comers in sonorous splendour. But the prime reason for acquiring the Böhm version is Fritz Wunderlich’s Tamino: elegance, ardour, a glorious, free-ringing top register and the finest legato of any tenor in the role.

Upping the tempo

A decade before Klemperer and Böhm, Ferenc Fricsay was the earliest conductor on disc to adopt brisk, ‘modern’ tempos. Only an ultra-perky ‘Bei Männern’ (‘Mann und Weib’, as Mozart dubbed it) misses the mark. It’s good to hear Pamina’s aria done at a gentle two-in-a-bar lilt. Maria Stader is a cool, rather reserved Pamina, Fischer-Dieskau’s Papageno is even more self-consciously jaunty than for Böhm, and Rita Streich’s Queen convinces more in her first aria than in an underpowered ‘Der Hölle Rache’. Ernst Haefliger is a rather gentlemanly Tamino. The mono sound favours voices over a slightly papery orchestra, and again there’s an illusion-breaking disparity between the singers and the actors who speak their dialogue.

Moving into the 1970s and ’80s, the three recordings from Wolfgang Sawallisch, Colin Davis and Bernard Haitink all take a broadly similar approach as regards tempos – mainly on the stately side – and orchestral weight. The Masonic scenes, especially, can be burdened with an excess of worthiness. Still, there are some superb performances on all three. Sawallisch scores with the imperious Queen of Edda Moser, the ripe, teak-toned Sarastro of Kurt Moll, a true basso cantante, and the Tamino of the young Peter Schreier, who compensates in dramatic vitality and verbal point for what he lacks in honeyed warmth. No other tenor makes the portrait aria ‘Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön’ such a compelling emotional journey, from dazed wonderment to exultation. There’s also a natural ease to Schreier’s double acts with Walter Berry, a Papageno who makes you smile more than most.

On the Colin Davis recording we can savour the Dresden Staatskapelle’s distinctively soft, silken strings as the Three Ladies drool over Tamino. Schreier, his tone now slightly reedier, and the rock-solid Moll survive from Sawallisch’s recording. There’s an attractive, open-hearted Papageno from Mikael Melbye. But Lucia Serra’s Queen squeaks above the stave, while Margaret Price, superb as Countess Almaviva or Donna Anna, makes a coolly aloof Pamina, imperturbable in ‘Ach ich fühl’s’. Robert Tear goes way over the top as Monostatos. Melbye alone of the cast speaks his own dialogue.

Even more than Davis and Sawallisch, Bernard Haitink conducts a determinedly serious reading. There’s minimal sparkle, let alone humour, even from Wolfgang Brendel’s firmly sung Papageno. You’d barely guess that the opera had its roots in Viennese pantomime. But the female leads are both outstanding. Edita Gruberová has the ideal technique and temperament for the Queen of the Night. By 1981 Lucia Popp had swapped mother for daughter. With poignancy woven into the very texture of her bittersweet timbre, she sings what is for me the most moving Pamina on disc.

Slightly against expectations, my pick of the large-scale, ‘traditional’ versions is Georg Solti’s 1990 recording with the Vienna Philharmonic. Tempos can be tensely driven but there’s a strong sense of an unfolding drama here, and minimal portentousness. The solemn scene outside the Temple of Wisdom between Tamino and the Speaker, so admired by Wagner, unfolds as a natural conversation between tenor Uwe Heilmann and baritone Andreas Schmidt, both fresh and youthful of tone. Michael Kraus sings an engaging, echt-Viennese Papageno, and Moll’s Sarastro is as majestically sonorous as ever. Ruth Ziesak is a vulnerable Pamina, in the right sense, Sumi Jo among the most accurate, if not most formidable, of Queens. The Three Ladies and Three Boys outclass all their predecessors.

A laborious, monochrome Speaker weighs down the crucial scene with Tamino in the 1993 Naxos recording from Michael Halász. Kurt Rydl’s Sarastro is a graceless wobbler and Hellen Kwon’s steely Queen screeches on sustained high notes. But Georg Tichy is a spontaneous-sounding Papageno, Herbert Lippert a sympathetic Tamino, shading and phrasing tenderly in the portrait aria.

Towards ‘authenticity’

A few years earlier Nikolaus Harnoncourt gave Die Zauberflöte a semi-period makeover with Zurich forces. He has an ideal pair of lovers in Barbara Bonney and Hans-Peter Blochwitz, sweet and pure of tone, and phrasing with a natural Mozartian grace. As with Haitink, Gruberová brings a demonic glitter to the Queen’s arias. The Papageno, Anton Scharinger, is unusually reflective; and as always, Harnoncourt has an acute ear for sonority, often tilting the balance towards wind and raw-toned natural brass. But some eccentric tempo choices, including a lingeringly romantic ‘Bei Männern’ and the substitution of a narrator for the dialogue, rule this out as a prime contender.

Likewise using modern instruments with a nod to period practice, Charles Mackerras conducts a brace of recordings, one in German, one in English. Drawing on what is known of 18th-century custom, Mackerras is an acute judge of tempo in Mozart. The spruce playing of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra in the German-language Telarc version is a constant delight. So, too, are Thomas Allen’s eager, handsomely sung Papageno (nothing wrong with vocal beauty in this role) and Robert Lloyd’s noble Sarastro. The aptly mobile tempo for ‘O Isis und Osiris’ allows him to phrase in broad spans. On the downside, Barbara Hendricks, with her bright, fluttery tone, is a bland Pamina, June Anderson a squally, word-shy Queen.

The cast on Mackerras’s English-language recording is more consistently satisfying. There’s a lot to be said for Mozart’s ‘comedy with machines’ sung in the language of the audience. So engagingly do the cast speak Jeremy Sams’s deft and witty translation that the (pruned) dialogue emerges naturally from the musical numbers. Lesley Garrett goes the full Doncaster as a sparky Papagena. Rebecca Evans movingly portrays Pamina’s development from ingénue to a woman ‘worthy to attain the light’, Barry Banks is a positive, scrupulously sung Tamino, Simon Keenlyside a wry, self-deprecating Papageno – an intriguing portrayal (you can see him in the role on a DVD from Covent Garden). Few recordings make you so aware of the originality of Mozart’s scoring, whether in the austere, hieratic colouring of the Masonic music or the ethereal sonorities of the music for the Three Boys.

A real whiff of the theatre from a youthful‑sounding cast: Abbado and his singers – including Christoph Strehl as Tamino (photography: Marc Theis/DG)

Claudio Abbado came late to Die Zauberflöte and his 2005 recording, taken from staged performances in Modena, has the freshness of first discovery. This is a Flute in the Mackerras mould, with nimble tempos and light, transparent textures from the fabulous Mahler Chamber Orchestra, not least in the unearthly sotto voce close of the Act 1 Quintet and the eerie-comic pianissimo strings and piccolo in Monostatos’s lustful solo. More than any version discussed so far, Abbado’s has the verve and spontaneity of a real performance. In speech and song, the singers are excellent, individually and as a close-knit ensemble. As the lovers, Christoph Strehl and Dorothea Röschmann, with a dark flame in her tone, balance wondering innocence and passionate urgency. René Pape, today’s finest German basso cantante, matches Kurt Moll in rounded depth and surpasses him in variety of colour and sheer humanity.

Yannick Nézet‑Séguin’s Chamber Orchestra of Europe rival Abbado’s band in quivering vitality. Pacing, again, seems spot on, instrumental detail brilliantly observed. Incapable of a routine phrase, Christiane Karg sings a graceful, innig ‘Ach ich fühl’s’. Franz-Josef Selig makes an unusually human Sarastro, and Klaus Florian Vogt fines down his Wagnerian tenor with fair success as Tamino. Once acclaimed for his Rodolfo and Alfredo, tenor Rolando Villazón here morphs into Papageno. He has all the right intentions but in both timbre and style he can’t quite shake off his inner Puccini.

The gut-string brigade

Casting problems also dog the period-instrument versions from Roger Norrington and John Eliot Gardiner. Proving his anti-Romantic point, Norrington conducts the fastest Flute on disc. Some numbers verge on the garbled. Gardiner, never one to underplay an accent, is less doctrinaire, though the faster music can still feel harried. He has a delectable Pamina in Christiane Oelze, whose ‘Ach ich fühl’s’, phrased in long, grieving spans, achingly distils the girl’s loneliness and desolation. For mingled simplicity and vocal beauty few duos match Oelze and Gerald Finley in ‘Bei Männern’. But Cyndia Sieden is a lightweight, disengaged Queen (her coloratura evokes a mechanical doll on speed), Harry Peeters a feeble Sarastro.

Sheep’s gut and calf’s skin are more affectionately deployed in the versions from Arnold Östman and William Christie. Östman’s buoyant performance with Drottningholm forces has a wide-eyed ingenuousness that you feel Mozart would have applauded. The cast, all with lightish voices, blend well, and rattle happily through their dialogue. As on the Christie set there are neat touches of ornamentation. For my taste Barbara Bonney’s Pamina is too much the shrinking violet (she made a more positive impression with Harnoncourt), while Sumi Jo’s pinpoint-precise Queen again lacks venom.

Like Östman, William Christie, in his recording based on stagings by Robert Carsen, reminds us that Mozart wrote Die Zauberflöte for young voices. His lovers, Rosa Mannion and Hans Peter Blochwitz, are perfectly cast (the portrait aria sung with a gentle sense of wonder); and his Sarastro, Reinhard Hagen, sings with grave depth of tone while still sounding youthful. Christie’s flowing tempo enables him to encompass the first phrase of ‘O Isis und Osiris’ in a single span. Natalie Dessay is both brilliant and almost seductively delicate in the Queen’s stratospheric coloratura – an unusual take which Carsen justifies by suggesting that the Queen is in fact working with Sarastro towards a common goal of the lovers’ enlightenment (a DVD of his Baden-Baden staging makes the point). The Ladies, vivid both in their squabbling and their tongue-twisting patter, deserve the florid cadenza that Mozart later deleted from their opening ensemble. Christie’s finely nuanced direction is loving, flexible yet never indulgent. And the tangy period instruments of Les Arts Florissants have you marvelling anew at Mozart’s scoring, from the soft woodwind and muted trumpets and timpani at the opening of the Act 1 finale to the pungent trombones and basset-horns in ‘O Isis und Osiris’.

The theatrical effects on the Östman and Christie versions pale before those on the recording from René Jacobs, who with his crack Berlin period band seeks to create what he calls a ‘Hörspiel with music, a play for listening’. This is a version like no other. At the opening the Ladies veer between speech and Sprechgesang. A fortepiano is always likely to chip in with a chuckle or a flourish. All this ‘production’ might seem gimmicky. Yet, for me, it makes for entertaining radio theatre, enlivening stretches of potentially tedious dialogue. Tempos are fast but fluid. Only the luminous opening of the Act 1 finale, where Mozart’s Larghetto becomes a tripping allegretto, seems misjudged. Again, the cast is youthful-sounding, led by Marlis Petersen’s pellucid, urgently felt Pamina, and Daniel Behle, who sings Tamino’s portrait aria as a private meditation.

Flute on film

This highly selective survey allows space for only a handful of DVD recordings. Several have proved hard to come by, including the 1983 film of August Everding’s admired Munich production, conducted by Sawallisch, and with a cast that includes Popp, Gruberová and Moll (DG, 7/90, 4/06). Apologies if your favourite DVD version is missing.

Conjuring a fairy-tale vision of ancient Egypt, David Hockney’s colourful geometric set designs charm in John Cox’s Glyndebourne staging, conducted, rather deliberately, by Bernard Haitink. Felicity Lott and Benjamin Luxon are a delightful Pamina and Papageno. At the opposite extreme from this innocence, Martin Ku≈ej, in his Zurich production conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, stages Die Zauberflöte as a nightmarish fantasy. The singers are no more than fair-to-good, while Harnconcourt’s highly interventionist conducting is by turns illuminating and perverse. Ending with the lovers half-traumatised, Ku≈ej’s unmagical Konzept leaves a nasty taste in the mouth, exactly what Flute shouldn’t do.

More coherent, and far more uplifting, is David McVicar’s Covent Garden production, conducted by Colin Davis (2003) and Julia Jones (2017). Drawing on references ranging from Hogarthian grotesques (Monostatos and the slaves) to the Enlightenment’s pursuit of scientific truth (the Temple of Wisdom becomes an 18th-century laboratory), McVicar’s concept is essentially serious though shot through with moments of childlike charm, such as the dancing animals in the Act 1 finale. In the Davis recording tempos are predictably spacious, occasionally inert. The trio ‘Soll ich dich Teurer nicht mehr sehn?’ is becalmed, almost like a freeze frame. But there are outstanding performances from Dorothea Röschmann, an anguished, uncommonly passionate Pamina, Diana Damrau’s icily glittering Queen, decked out like Cruella de Vil, and Simon Keenlyside’s sad clown of a Papageno, more Samuel Beckett than Viennese Hanswurst.

In 2017 Julia Jones opts for swifter tempos (not least in ‘Soll ich dich Teurer’) and lighter, period-style articulation. There is more overt comedy here, often courtesy of Roderick Williams’s bemused, put-upon Papageno, forever prone to pratfalls. The Pamina sounds like a displaced Verdi soprano. But Sabine Devieilhe, shaping and colouring her coloratura, is another show-stopping Queen, Mika Kares a kindly, deep-toned Sarastro.

In a production staged first at La Monnaie, South African artist William Kentridge downplays the Freemasonry and sets the opera in the context of late 19th-century African colonialism. With immediate distancing effect, the Three Ladies ogle Tamino through a box camera. The cinema becomes a pervasive metaphor. As Kentridge notes in the booklet: ‘This production is almost set inside the centre of a camera – as if we in the audience are watching the making of sense inside the black box of that camera.’ Image tumbles upon image in black-and-white video projections. A dancing rhino charmed by Tamino-as-Orpheus symbolises an ideal harmony between the human and natural worlds. When an ambivalent Sarastro, representing the older generation, sings ‘In diesen heil’gen Hallen’ we see a rhino being hunted in the bush. Kentridge’s projected images dazzle, intrigue and amuse, though it can all seem a bit frenetic on the small screen. Roland Böer, who obviously knows the René Jacobs recording, conducts with brio. As caught by the microphones too much of the singing is too loud, though Albina Shagimuratova is a Queen to reckon with, while Genia Kühmeier sings and acts Pamina with ingenuous grace.

Pavol Bresik as Tamino in Robert Carsen’s Rattle-conducted Baden-Baden production (photography: Andrea Kremper)

Equally provocative but more cohesive is the staging by Robert Carsen, conducted at Baden-Baden by Simon Rattle. In his modern-dress production the Queen and Sarastro are allies rather than antagonists, holding hands in ‘In diesen heil’gen Hallen’. From the opening scene, where Tamino struggles out of a newly dug grave, death and resurrection are recurrent images. The old woman who metamorphoses into Papagena appears in a cemetery as a skeleton in a bridal outfit. There is, though, more antic fun (not least in the dialogue), and more eroticism, than in either the Kentridge or McVicar stagings. The Three Ladies are a camp cabaret act. But there is solemnity and stillness where needed, plus plenty of innocent charm. Epitomising the message of light triumphing over darkness and life over death, even Monostatos joins in the final chorus. Rattle conducts the Berlin Philharmonic with a twinkling lightness of touch. The young cast, all of whom take well to the camera, include Ana Durlovski as a sexy, humanised Queen, and Kate Royal and Pavol Breslik, prioritising lyrical simplicity as the lovers. If I had to live with one Zauberflöte on film, this would be it.

The final cut

As to CD recordings of this protean opera, Solti, Mackerras and Nézet-Séguin have their claims, ditto the period versions from Östman and Gardiner. Among traditionally conceived – which tends to mean slow – performances I’d need Böhm for Wunderlich, Klemperer for Janowitz’s Pamina and Popp’s peerless Queen, and Haitink for Popp’s Pamina – a unique double triumph for the Slovak soprano!

But forced to choose just three versions, as the rules of the game dictate, I’d plump for William Christie’s lovingly detailed period performance, René Jacobs for inventiveness and an irreverent, echt-Mozartian sense of fun, and the flawlessly paced, finely sung Abbado, whose Modena performance combines the polish of a studio recording with the theatrical energy of a live staging. In each of these three performances, dialogue and song flow naturally into one another. And for all their sophistication, they remind us that Die Zauberflöte is popular theatre raised to a supreme level. The Masonic scenes have an unstuffy gravitas. Elsewhere there is a freshness and innocence too often lost in more Romantically inclined performances. Most crucially, in all three recordings the young lovers bring a rapt tenderness and simplicity to their reunion in the Act 2 finale: a moment of transcendent grace that sets the seal on Mozart’s sublime Enlightenment parable-pantomime of redemption and reconciliation.

Period-Instrument Choice

Les Arts Florissants / William Christie Erato

Drawing ravishing colours from his period band, Christie directs a performance at once theatrically vital and lovingly detailed. Lyrical tenderness is a priority. The pacing is lively and supple, and the singers, fresh from staged performances, ideally chosen. Natalie Dessay dazzles as the Queen of the Night and Anton Scharinger’s engaging Papageno is more reflective than most.

Left-Field Choice

AAM Berlin / René Jacobs Harmonia Mundi

With its lavish theatrical effects and irrepressible fortepiano commentaries, this is the marmite version. You either succumb or switch off. Jacobs has his interpretative quirks but I find his Flute-as-radio play both musically satisfying and hugely entertaining, not least when the Three Ladies are involved. There are pungent colours from the Berlin period band, and a true and touching pair of lovers.

DVD Choice

BPO / Simon Rattle Berliner Philharmoniker

No filmed Flute will satisfy everyone. Robert Carsen’s concept, with the Queen and Sarastro working together for the lovers’ enlightenment, is controversial. But the imagery, partly inspired by the Orpheus myth, is both thought-provoking and smile-inducing. Carsen’s vision of harmony at the end is strangely moving. All the characters look and sound convincing, and Rattle conducts with a a light, affectionate touch.

Modern-Instrument Choice

Mahler CO / Claudio Abbado DG

With so many variables at play, it inevitably boils down to taste. But if any conductor gets everything spot on, it’s Abbado, in a performance that holds gravitas, innocence and airy lightness in ideal balance. There’s a real whiff of the theatre, while the youthful‑sounding cast, including Erika Miklósa’s fiery Queen and Hanno Müller-Brachmann’s endearing Papageno, has hardly been bettered.

This article originally appeared in the March 2023 issue of Gramophone magazine. Never miss an issue of the world's leading classical music magazine – subscribe to Gramophone