Review - Jorge Bolet: Complete Decca Recordings

Tim Parry

Friday, February 21, 2025

Tim Parry explores the legacy of Jorge Bolet’s Decca recordings

Two statements about Jorge Bolet are often repeated: first, that his Decca contract came a decade too late, the resulting recordings capturing a pianist with declining physical powers; and second, that he was a pianist who played better live in front of an audience than in the recording studio. If we accept these observations then it follows that this handsome box-set from Decca, of the complete recordings the pianist made for the label from 1977 until his death in 1990, presents only a partial picture of Bolet’s artistry. Yet it still offers an invaluable portrait of one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, a legacy that it seemed would elude Bolet for most of his professional life.

There is an element of luck in any musician’s career – being heard by the right people in the right place at the right time – and Bolet was unlucky. His performances were consistently well received, yet wider recognition came slowly. Born in Cuba in 1914, at the age of 12 Bolet went to the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, where he studied with David Saperton (Godowsky’s son-in-law), graduating in 1934. Concerts in Europe and America followed but the war inevitably interrupted progress, and the post-war years were marked by repeated setbacks. He did make a few LPs in the early 1950s, including the first recording of Prokofiev’s Second Concerto, but made no studio recordings between 1961 and 1968, when he should have been in his prime. His breakthrough came in 1970, a month before he turned 56, when he performed at a benefit concert in New York for the International Piano Library, which had been vandalised. Bolet’s performance of two Liszt opera paraphrases was the standout contribution from a line-up of pianists that included Alicia de Larrocha, Earl Wild, Raymond Lewenthal, Rosalyn Tureck and Guiomar Novaes. This success led to a Carnegie Hall recital on February 25, 1974, that was recorded and issued by RCA – an event that secured Bolet’s reputation. One of the greatest of all live piano recordings, culminating in a titanic account of Liszt’s arrangement of Wagner’s Tannhäuser Overture, this formed the basis of the two‑disc Bolet volume in Philips’s Great Pianists of the 20th Century series.

At its best, Bolet’s playing was renowned for its beauty and richness at every dynamic level, glorious singing tone, aristocratic mastery and unfailing sense of musical line

In February 1977 Bolet gave a recital at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall. The sparse audience included the young Decca producer Peter Wadland, who oversaw the Decca-owned L’Oiseau-Lyre label, which specialised in early music, but whose greatest passion was old-school piano-playing. After the triumphant concert, Wadland – who in a tribute to Bolet in Gramophone (1/91) misremembered the year as 1976 – persuaded Bolet to make a Godowsky album for L’Oiseau-Lyre, which was recorded at Kingsway Hall in October 1977. This was the start of a relationship that lasted for the rest of Bolet’s life.

On October 2, 1977, Bolet returned to give another recital at Queen Elizabeth Hall, when his encores included Godowsky’s arrangements of a handful of Chopin’s études and waltzes. The following day he went into the studio to record these on his first album for L’Oiseau-Lyre and comparisons illustrate the essential difference between Bolet’s playing in concert and in the studio: the live versions (an audience recording of the October 2 recital can be heard on YouTube) are generally a notch faster and exude a suave elegance and generosity of spirit that in the studio give way to magisterial refinement and precision. The Chopin-Godowsky album was a groundbreaking recording that brought these works to widespread attention, with a stately authority that set a benchmark in these pieces until Marc-André Hamelin recorded the complete Studies for Hyperion (5/00).

The Chopin-Godowsky album is disc 1 in this box-set, which presents Bolet’s Decca recordings in chronological order rather than grouped by composer, an approach that reveals the trajectory of Bolet’s playing during his final decade. A second LP for L’Oiseau-Lyre was recorded in December 1978, containing Liszt’s five Études de concert and Réminiscences de Don Juan. Again, in music with virtuoso sophistication at its heart, Bolet’s playing is crystalline and vividly characterful without descending to superficial exhibitionism. Others bring greater brio to parts of the Don Juan Fantasy, but Bolet underpins it with an overarching drama and narrative. Next came an intriguing album coupling outstanding Reger (Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Telemann, which was on the programme of Bolet’s February 1977 QEH recital) with persuasive Brahms (Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel). This was Bolet’s first recording to be issued on Decca rather than L’Oiseau-Lyre.

Liszt was always central to Bolet’s repertoire. He dismissed the idea of being a Liszt specialist – ‘a specialist is someone who plays everything so much worse’, he dryly observed – yet Liszt’s music forms the backbone of this set. Bolet went on to record a further seven volumes of solo Liszt (the 1978 Concert Études/Don Juan recording appeared on CD in 1986, coupled with the 1985 recording of the Consolations, as it is in this new set). Among these are a powerfully lucid B minor Sonata and a noble account of the complete Études d’exécution transcendante, as well as the first (Suisse) and second (Italie) books of Années de pèlerinage. For the Suisse book, Bolet won a Gramophone Award in 1985 (‘One cannot quite say that this is the best volume of Bolet’s Liszt series, yet it is the one that we needed most,’ wrote Max Harrison, 10/84). But the highlight of Bolet’s Liszt is the selection of transcriptions of Schubert’s songs, where the pianist’s lyrical refinement and gorgeous singing tone – aided by generous and sophisticated pedalling – come to the fore. Many great pianists since have excelled in Liszt’s Schubert arrangements – from Yuja Wang and Volodos to Chamayou and Kantorow – but few have matched Bolet’s poetic eloquence and clarity of line.

Bolet’s championing of Liszt was much needed in the 1980s for its articulacy, discerning refinement and complete lack of vulgarity. There are times when caution gets in the way of excitement, muting Liszt’s rhetoric, a characteristic more evident in Bolet’s studio work than in the concert hall. Sometimes this is simply a question of tempo – whether evading the cheap thrill of a work such as the Grand galop chromatique or restricting the galloping hooves of ‘Mazeppa’ to a gentle canter. Sometimes it’s an expressive choice – the Petrarch Sonnets, from the Italian book of Années de pèlerinage, prioritise lyrical beauty over a more urgent sense of passion. Yet these performances are unfailingly poetic and communicative, a powerful antidote to faster fingers and emptier musicianship.

These recordings have a distinctive sound world, for which the engineering and perhaps Bolet’s choice of instrument are at least partly responsible. For all the clarity of the sound, there is often a distinctive metallic edge to the treble, which can colour Bolet’s natural singing tone and accentuate his musical gestures. Throughout his career, rather than Steinways Bolet preferred to play Baldwins in America and Bechsteins in Europe. His choice of Baldwin pianos stemmed from loyalty and the company’s support for him in his early years – Bolet named his dog Baldwin – but he ended up preferring what he considered to be the greater tonal richness and more subtle soft pedal effect of their instruments. Not everyone agreed. Peter Wadland relates that when Bolet arrived at Walthamstow Assembly Hall in London in 1986 to record Chopin’s Ballades, the Bechstein that had been supplied was in such a terrible state that Bolet instead used a Steinway. Bolet apparently didn’t like the sound on this album, although to my ears – and to Wadland’s – it is detailed and colourful. From 1987 Bolet played Baldwins everywhere.

Although Liszt is at the core of this set, there is plenty of other repertoire. Three discs are devoted to Chopin (and there is an additional, previously unpublished disc of nocturnes, of which more later). In addition to the four Ballades – graceful, low-voltage accounts, coupled with a superb F minor Fantasy and an exquisite Barcarolle – there followed the Op 28 Preludes, where the playing is lyrical and measured but pales alongside the 1974 Carnegie Hall performance. In 1989, already in ill health, Bolet recorded the two Chopin concertos in Montreal with Charles Dutoit (the F minor Concerto was not in his active repertoire and he had to learn it specially), autumnal readings that seem at odds with the music’s youthful flair and exuberance.

There is a beautiful account of Rachmaninov’s Third Concerto, richly detailed if in places lacking rhythmic drive (most notably in the finale), and a fine disc of solo Rachmaninov that includes a terrific Chopin Variations alongside shorter pieces. Bolet’s Schumann – Carnaval and the C major Fantasie – has many lovely things despite the slow tempos, the highlight being the inward and deeply atmospheric finale of the Fantasie. In César Franck’s Symphonic Variations, which used to be heard more frequently, Bolet is perceptive and idiomatic.

Discs of the Grieg and Schumann concertos and of Tchaikovsky’s First and Rachmaninov’s Second, as with the Chopin concertos, are disappointing, with insufficient inner life and interest to compensate for the safety-first approach. Bolet didn’t play Debussy often, and his album of 16 Préludes, moving freely between his selections from both books, is cool and insufficiently characterful. His Schubert sonatas, D784 and D959, were recorded in 1989 and the playing is probing and austere, at times deeply poignant, at others wearily pedestrian; this was well described by Joan Chissell (12/90) as ‘an elder statesman’s Schubert’.

In February 1990, severely ill (he died in October that year), Bolet went to Davies Symphony Hall in San Francisco, still with his trusted producer Peter Wadland (who himself died in 1992 at the age of 46), to record Chopin’s Second and Third Sonatas, the Berceuse and a selection of nocturnes, none of which were issued. The sonatas were probably not completed, but this set includes – issued here for the first time – the seven nocturnes and Berceuse. Tempos are uniformly slow, even for late Bolet. As the playing of an ill man a few months before he died, it might be seen to have a valedictory air that is moving, but ultimately it adds little to our understanding. Evidently transferred from a cassette source, the sound is unsteady and compromised, and it’s a pity that Decca was unable to use the original masters.

At its best, Bolet’s playing was renowned for its beauty and richness at every dynamic level, glorious singing tone, aristocratic mastery and unfailing sense of musical line. Yet, for all the marvels in this set, to best experience these qualities and understand why Bolet is widely considered to be one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, you have to listen to his live recordings. Bolet was aware that he was at his best in front of an audience, and he encouraged people to tape his concerts and to share audience recordings. Consequently, there is a large amount of live material available, whether from bootleg sources or radio broadcasts. Marston has issued two sets – eight discs in all – that select some of the finest examples, and these are essential to appreciating the richness of Bolet’s artistry. There are also many examples on YouTube that are well worth exploring.

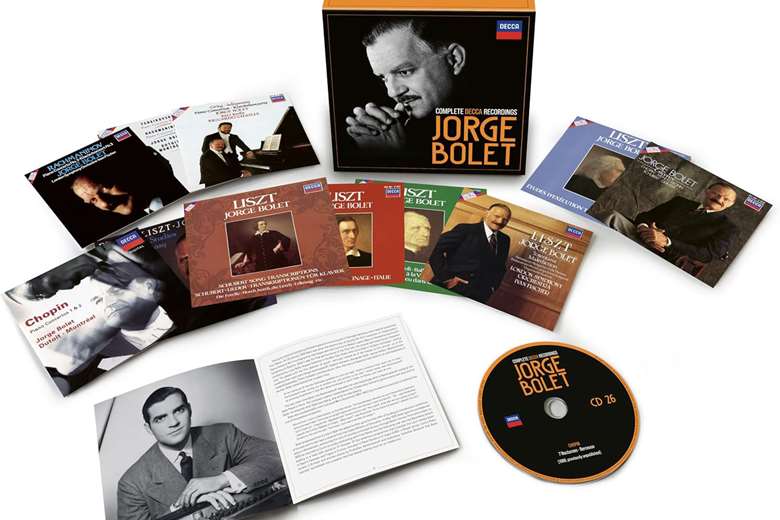

This Decca box may represent only part of Bolet’s legacy, but we should be grateful that his late playing was so extensively and sympathetically captured on record. With original-jacket sleeves and a detailed booklet with excellent notes by Jonathan Summers and lots of wonderful photographs, this set – selling for a little over £100 in the UK – is a magnificent tribute to a great pianist.