Review - Charles Ives: The RCA and Columbia Album Anthology

Friday, January 24, 2025

Richard Whitehouse on an inviting anniversary collection devoted to Charles Ives

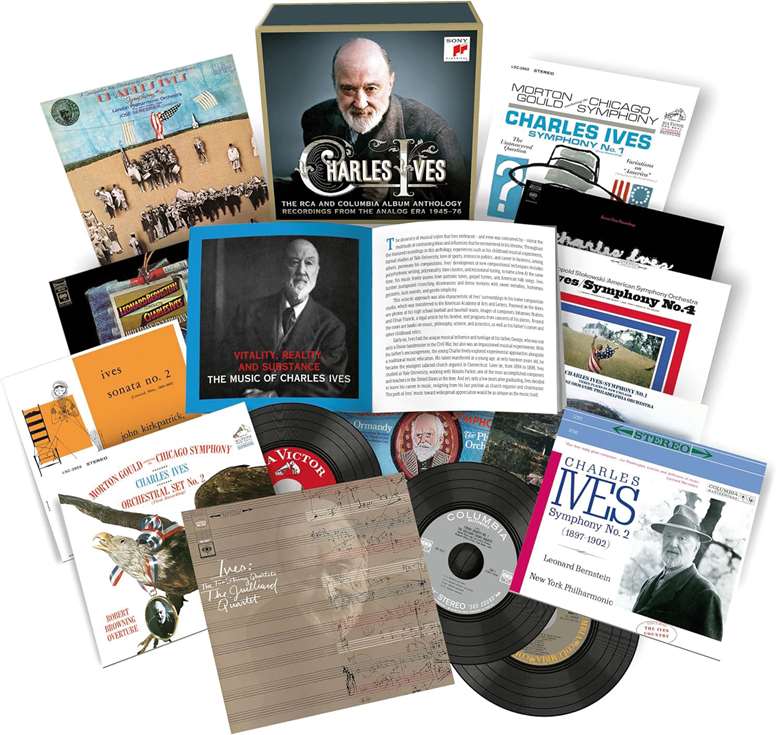

The 150th anniversary of Ives’s birth has been notable more for its reissues than new releases, but the archives constitute a treasure trove. Charles Ives: The RCA and Columbia Album Anthology contains almost all this composer’s principal works, some in multiple versions.

Nicolas Slonimsky set down Ives’s music as early as 1934, but it was John Kirkpatrick’s 1945 Concord Sonata that established Ives in recorded terms – this hectic yet superbly articulated account retaining all its pioneering immediacy. William Masselos did likewise with the more uninhibited virtuosity of the First Piano Sonata in 1950; at this time, Patricia Travers and Otto Herz made their tensile reading of the Second Violin Sonata (the only one of Ives’s four such works here). While not its first recording (by F Charles Adler in 1953), Leonard Bernstein’s 1958 Second Symphony confirmed Ives as the first American composer of stature and, for all the pitfalls of this edition or of Bernstein’s own liberties, its proselytising zeal is undimmed.

The mid- and latter 1960s saw a deluge of Ives ‘firsts’. Above all, Leopold Stokowski in the Fourth Symphony – its second movement bordering on chaos and its finale unduly headlong, but a visceral experience this conductor repeated with the recalcitrant and (unfairly) unloved Robert Browning Overture. Bernstein is inflexible, even hectoring in the deceptively placid Third Symphony but secures a tangible atmosphere in the contrasted ‘contemplations’ of The Unanswered Question and Central Park in the Dark, as does E Power Biggs in the teenager’s Variations on ‘America’, redolent more of the fairground than the organ loft. William Schuman’s 1962 orchestration responds to Morton Gould as a spirited up‑beat to the First Symphony, but this latter is a little earthbound next to Eugene Ormandy’s characterful reading or his dynamic account of Three Places in New England. Gould comes into his own in the Second Orchestral Set, not least the transcendent fervour of its finale, and an impulsive if disciplined Browning Overture. Bernstein tackled A Symphony: New England Holidays at four separate sessions yet such evocative power is its own justification, with the finale unequalled for rhetorical fervour.

Alongside such often-reissued recordings are pioneering collections little distributed outside the US. ‘Music for Chorus’ features five choral songs, their implacability complementing the suffused warmth of the Harvest Home Chorales, and five psalm-settings of which the starkly austere Psalm 90 is Ives’s choral masterpiece (and a likely influence on Leonard Rosenman’s score for Beneath the Planet of the Apes). Gregg Smith is the authoritative conductor here as on ‘New Music of Charles Ives’ with four further psalm-settings, including a combative Psalm 25, while a group of mainly later songs benefits from the sensitivity of Adrienne Albert and William Feuerstein. The Juilliard Quartet in both string quartets was long a benchmark – the First being Ives’s earliest large-scale piece to use traditional music (hymns in this instance); the Second a journey towards transcendence and his most perfectly realised work. Masselos’s less spontaneous remake of the First Piano Sonata appeared just prior to Kirkpatrick’s of the Concord, its textual amendments and tempo adjustments a touchstone for future recordings.

Into the 1970s, when ‘Chamber Music’ saw the formidable duo of violinist Paul Zukofsky and pianist Gilbert Kalish joined by cellist Robert Sylvester for a perceptive account of the Piano Trio, not least its finale’s slow-burning intensity. Also here are several ‘take-offs’ ominous or uproarious, and an early Largo for violin and piano of real pathos with or without clarinettist Charles Russo. Gunther Schuller’s ‘Calcium Light Night’ was the first in-depth exploration of those miniatures that enshrine the essential Ives, which The Incredible Columbia All-Star Band render with alacrity. No less idiomatic are James Sinclair and the Yale Theater Orchestra, ‘Old Songs Deranged’ being a precursor of similar collections by this doughtiest of Ives advocates.

‘American Scenes – American Poets’ is a valuable overview of songs, eloquently done by Evelyn Lear and Thomas Stewart with Alan Mandel. Ormandy recorded his thoughtful account of the Third Symphony early in his RCA years, yet his Second has only its cultured string-playing to offset a lack of emotional involvement. Nor does his remake of the First Orchestral Set match that for CBS, but his Holidays has a finale equal to Bernstein for emotional breadth. Having assisted Stokowski on the Fourth Symphony, José Serebrier was sole conductor for a reading that is over-produced but has just the right gravitas in its finale. The Cleveland Quartet give a probing Second Quartet, but the coupling with Barber would have pleased neither composer.

Remastering has much improved on the vinyl or shellac originals, while the booklet’s detailed track-listings and recording dates along with LP-cover reproductions is exemplary. Those who want Stokowski’s recording of secular choruses, Smith’s of the cantata The Celestial Country or Helen Boatwright’s song anthology should head to Sony’s companion reissue ‘Charles Ives – The Anniversary Edition’ (19658 88597‑2). Both are essential additions to any Ives collection.

The recordings

Ives The RCA and Columbia Album Anthology: Recordings from the Analog Era 1945-76

Various artists (Sony Classical (22 CDs) 19658 88596-2)