Echoes of Genius: From the Dawn of Electrical Recording to Hidden Violin Treasures

Rob Cowan

Thursday, April 17, 2025

Rare and revelatory, these archival releases span a century of recording history – from the crackling ghosts of 1925 to the lyrical power of forgotten greats like Elman, Varga, and Stanske

This year marks a century since the advent of commercial electrical (ie microphone as opposed to horn) recording. Nevertheless, a handful of experimental discs using the process, or something fairly like it, stretch back as far as 1920, as is proved in the context of Pristine Classical’s fascinating 1925 anthology, being an audio glimpse of Armistice Day 1920 in Westminster Abbey during the ceremony of the interment of the Unknown Soldier of the First World War. Although hardly a vivid advertisement for the new process (the pitch drops dramatically at the very start of Abide with me but quickly recovers), some of the featured recordings of ‘light’ as well as ‘classical’ music defy their age.

Here we have 26 tracks in all, including Giuseppe De Luca’s incomparable rendition of Cimara’s song ‘Stornello (Son come i chichi)’, Margarete Matzenauer singing a Mexican folk song and Alfred Cortot as a model of eloquence in his own transcription of Schubert’s ‘Litany’, a real prize of a track. Among the orchestral items, Leopold Stokowski conducts the Philadelphia Orchestra in Saint-Saëns’s Danse macabre (with bassoons standing in for timps) – good for sure, but no match for his spectacular 1936 recording (Biddulph) – and there’s Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony in an exciting and individual reading by the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra under Landon Ronald with a tuba reinforcing the double basses. It’s a fascinating programme, based largely on records mentioned in Roland Gelatt’s celebrated book The Fabulous Phonograph, (1956, rev 1977), and it would be great if Pristine could repeat the exercise up to and including, say, 1930.

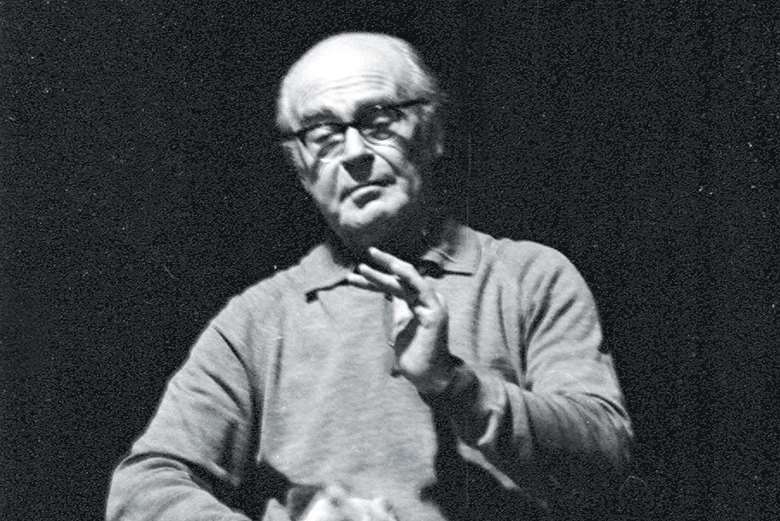

While on the subject of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth, Janus Classics has released a 1962 stereo recording by the Orchestre National de la RTF under Paul Kletzki (originally on Disques Festival), who had also recorded Tchaikovsky with the Philharmonia (now on Warner Classics), estimable versions of the Pathétique and Manfred Symphonies as well as the Serenade for Strings. Although sound-wise the symphony’s opening fanfares on horns and bassoons emerge as somewhat hollow, the main body of the work comes across rather well, with – unless my ears deceive me – antiphonally placed violins, and appreciative reportage of some extremely exciting climaxes; the finale’s coda is especially thrilling. Kletzki’s Tchaikovsky is filled with temperament, whereas his Beethoven, although admirably intelligent, treads a more straightforward path. His complete cycle for Supraphon with the Czech Philharmonic, with its airy woodwinds and incisive strings, has long been a personal favourite and I was therefore delighted to encounter Janus Classics’ release of a 1962 recording of the First and Fifth Symphonies with the Südwestfunk Symphony Orchestra Baden-Baden, both performances – and recordings – far weightier than their Czech alternatives, the Fifth lacking its first-movement exposition repeat (the Czech recording includes it), though both readings have a directness about them that is characteristic of Kletzki at his best. The sound is excellent, again relating divided violin desks (not a feature on the Czech cycle). The First Symphony has its repeats intact and is equally compelling. A Baden-Baden Eroica features some marked ritardandos in the first movement which won’t be to everyone’s taste but elsewhere Kletzki interprets with rigour, humility and an obvious love for the score. All these recordings have been transferred, edited and remastered in 32bit/192kHz.

Arturo Toscanini’s first broadcast with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, on Christmas Night 1937, was issued some while ago by Pristine Classical (PASC275) and included two items that turned up again in March 1939 when Bruno Walter took the reins from the maestro. Both performances of Mozart’s Symphony No 40 are pretty nifty. Walter’s is in general a milder beast than Toscanini’s (he omits the first-movement exposition repeat, whereas Toscanini includes it) until you reach the finale, which is both better played than Toscanini’s (the orchestra had by then had two years to get into its stride) and at 1'59" the violas’ attack is intense to a fault. Mind you, William Primrose was among the players, though never as principal. As to Brahms’s First, needless to say the more headstrong Toscanini rushes in at a faster tempo but in the Andante sostenuto slow movement both conductors are memorably lyrical, Toscanini audibly vocalising over the music.

The new Walter double-pack also includes another work that Toscanini programmed with the NBC SO, Mozart’s Divertimento No 15 in B flat, K287 (the RCA recording from November 18, 1947, is justly famous). Differences between the two include alternative Minuets and fewer variations in the second movement under Walter. Also with Walter, a fiery Mozart D minor Piano Concerto, which the conductor directs from the keyboard (as he did in Vienna for HMV pre-war), Haydn’s Oxford Symphony (No 92) and Weber’s Oberon Overture. Passing quibbles aside, this is fabulous music-making, playing of the highest order, captured in excellent sound for the period.

The recordings

1925 Landmarks from the Dawn of Electrical Recording

Various artists (Pristine Classical PASC734)

Tchaikovsky Sym No 4

RTF Nat Orch / Kletzki (Janus Classics JACL4)

Beethoven Syms Nos 1 & 5

SWF SO / Kletzki (Janus Classics JACL2)

Beethoven Sym No 3

SWF SO / Kletzki (Janus Classics JACL1)

Bruno Walter at the NBC, Vol 3

(Pristine Classical PASC722)

Elman in his prime

I’m not certain whether Walter or Kletzki ever accompanied that most maverick of romantic violinists, Mischa Elman, but if they did they would have had their work cut out following Elman’s rhapsodic, rhythmically free and alarmingly malleable playing of Tchaikovsky and Bach (E major) concertos, something the young John Barbirolli did in his stride back in 1929 (Tchaikovsky) and 1932 (Bach). To think that a few years later he would record the Tchaikovsky with Jascha Heifetz as the soloist, Heifetz as classically elegant as Elman was deeply subjective, even wayward. But with a tone that was second to none in its richness and expressive individuality, a mastery of rubato that was deeply personal and marked portamentos that were quite unlike anyone else’s, this account of the concerto makes for a unique listening experience, even if it can be brooked only once in a while.

The Bach for me is even more special, the central Adagio sounding like Bach’s Passion music, devotional in song and spirit, always sincere, though hardly prophetic of HIP! The other items are Vivaldi’s Concerto Op 12 No 1 arranged by Tivadar Nachéz and the two Beethoven Romances, all three (from 1931‑32) conducted by Lawrance Collingwood. Memorable as these are, the real prizes are the Tchaikovsky and Bach concertos, which – like the rest of the CD – have been excellently transferred by Rick Torres. Wayne Kiley has provided excellent notes.

The recording

Bach. Tchaikovsky. Vivaldi Vn Concs

Mischa Elman (Biddulph 85052-2)

Varga on the radio

Hungarian-born Tibor Varga (1921-2003) was a very different player to Elman, his vibrato faster, his tone less voluptuous, his approach tauter, his manner at once more direct, less heated. But he certainly had something to communicate about everything he played, as is amply illustrated by Meloclassic’s excellent (and very well refurbished) double album of ‘Early Radio Recordings’. Performances of concertos by Tchaikovsky (under Carl Garaguly, 1954) and Mendelssohn (Eliahu Inbal, 1970), treat virtuosity as side play but are in the main feelingly interpreted and lyrical. Schubert’s Rondo in A, D438 (with Varga’s own Chamber Orchestra, 1957) is as stylish as any version I’ve heard, but for me the unexpected highlight of the set is a 1957 studio recording of Alban Berg’s Concerto with the Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra under Georg Solti, as much for Solti’s approach to the score as for Varga’s. Try the huge orchestral strides from around 1'11" into the second movement, which also harbours, later on, reference to Bach’s Cantata No 60 (‘O eternity, you thunderous word’) at 8'00", played by Varga with an abundance of feeling, Solti’s Cologne wind section following on in like manner. I don’t think I’ve ever heard a recording of the Berg that is more moving than this, even if the orchestra isn’t exactly top-notch. Other music on the set includes showpieces by Sarasate, Ravel, Saint-Saëns and, perhaps best among them, a stunning unaccompanied live recording of Kreisler’s Variations on a Theme of Corelli. Recommended, and not just for curious fiddle buffs.

The recording

Early Radio Recordings

Tibor Varga (Meloclassic MC2061)

Discovering Stanske

If Tibor Varga is a name remembered only by a select coterie of connoisseurs, Berlin-born Heinz Stanske (1909‑92) is, as Meloclassic bills him, more a ‘rediscovery’, who became concertmaster for the UFA-Tonfilm Orchester in Berlin. And his sound? ‘Of his day’, I’d say, without being especially distinctive, even occasionally a little nervy, though exciting in fast passagework – and there are some concerto highlights that are well worth hearing. One is by the German composer and Kapellmeister Richard Mohaupt (1904‑57), heard in a recording from the year of his death, where he conducts the Südwestfunk Symphony Orchestra. Its highlight is a gently pulsing central Nocturne. Straight after Mohaupt’s Concerto we’re treated to a sassy 1957 performance of Milhaud’s Le boeuf sur le toit (also known, in the violin-and-piano arrangement, as Cinéma fantaisie), where Stanske plays the version for fiddle and orchestra, incorporating what sounds like Honegger’s cadenza (used in the version for violin and piano). His playing is a fair match for René Benedetti as heard on the 1928 Erato recording with pianist Jean Wiéner (Warner Classics).

It’s good to hear the Sibelius Concerto under Franz Konwitschny, a gruff, dark-hued orchestral reading to contrast with Stanske’s relative leanness and drive. Prokofiev’s Second Concerto (1956, under Hans Müller-Kray) suggests Heifetz as an influence, as does the Glazunov Concerto, though there, as with Varga’s Berg, the conductor (in this case the film-music composer Kurt Schröder, 1953) brings out countless details in the score we virtually never hear. During the 1930s Schröder worked in Britain for Alexander Korda’s London Film Productions. Other works programmed include Sarasate’s Concert Fantasy on Gounod’s ‘Faust’ (1957) and Bruch’s First Concerto under Edouard Van Remoortel (1963). Both of these Meloclassic CDs are superbly annotated.

The recording

Rediscovery of a Violinist

Heinz Stanske (Meloclassic MC2062)