Replay (January 2025): Stokowski specials; Rabin rarities; A second lark ascending

Rob Cowan

Friday, January 3, 2025

Rob Cowan’s monthly survey of historic reissues and archive recordings

Stokowski specials

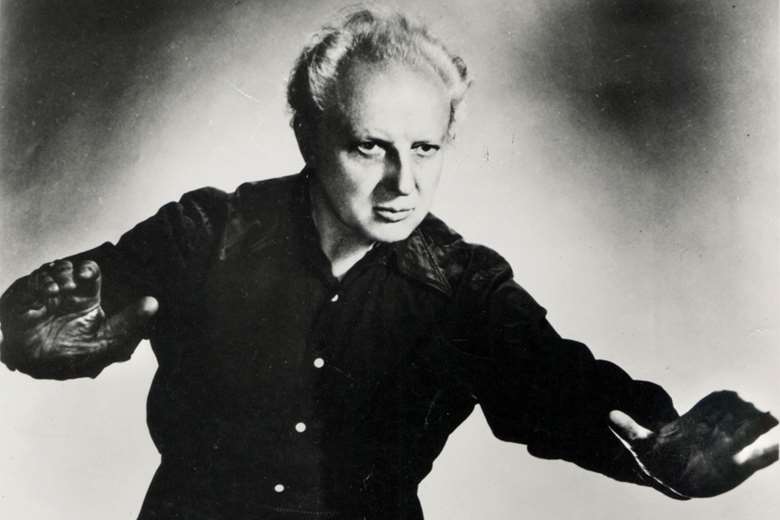

Few conductors in the history of recording set down as many memorable discs as Leopold Stokowski, starting in Philadelphia during the acoustic era for Victor, then in the 1940s through to the 1970s with various orchestras for numerous labels. Marston is preparing a four-disc set, ‘Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra Bell Laboratory Experimental Hi-Fi and Stereo Recordings, 1931‑1932’ – watch this space – but in the meantime Alto’s 10-disc collection of the ‘Complete Everest & Vanguard Recordings’ (gathered together for the first time) is supplemented by a small number of ‘extras’, including tracks from a fabulous stereo Capitol LP titled ‘Landmarks from a Distinguished Career’. Try Debussy’s Clair de lune (arranged by Stokowski), Prélude à L’après-midi d’un faune or Sibelius’s The Swan of Tuonela, and I challenge you to match them with rival recordings – either earlier or later – that are more charged with atmosphere or more beautifully played. All three are quite simply exquisite, Stokowski at his peerless best.

So much for the bonus CD (Disc J), though the same disc contains many other memorable tracks. Producer Bert Whyte and engineer Aaron Nathanson were responsible for the spectacularly vivid ‘Everest original masters recorded on 35mm magnetic film’, sound that is literally that, cinematic in the extreme. Brahms’s Third Symphony (Houston SO, 1959) blazes into action with maximum energy but perhaps the most famous Everest Stokowski recording is a coupling of Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini and the symphonic fantasy Hamlet (both with the Stadium Symphony Orchestra of New York, aka the New York Philharmonic, 1959), red-blooded performances that still deliver big-time. This is Tchaikovsky played at white heat, with no compromises for the sake of surface polish.

Strauss tone poems (Till Eulenspiegel, Don Juan, Dance of the Seven Veils, SSO of NY, 1959) and orchestral Wagner (from Parsifal and Die Walküre) are almost as impressive, but for me it’s a Prokofiev coupling that proves unforgettable, a 23'38" suite from Cinderella (SSO of NY, 1959) where the percussive chimes of midnight have surely never sounded with such dramatic impact on disc, and The Ugly Duckling as related by soprano Regina Resnick with a candour and sincerity worthy of Danny Kaye at his most endearing (SSO of NY, 1961). Not quite so sure about Peter and the Wolf with ‘Captain Kangaroo’ (American listeners of a certain age may be more responsive than I was) and a coupling of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra (Houston, 1961) and Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony (SSO of NY, 1958).

Disc E opens with Scriabin’s Poem of Ecstasy (Houston, 1959), sonically spotlit and interpretatively sensual, then switches to the Rimsky-like music of the Soviet and Azerbaijani composer Fikret Amirov, who created a genre called ‘symphonic mugam’. Three Chopin piano pieces are transformed into vivid sound pictures, the like of which only Stokowski could conjure (Houston, 1960), and as for Americana, Thomas Canning’s Fantasy on a Hymn Tune by Justin Morgan for double string quartet and string orchestra owes not a little to Vaughan Williams; there are extracts from Virgil Thomson’s appealing film music for The Plow that Broke the Plains (with the Symphony of the Air, aka the NBC Symphony Orchestra, the film’s director Pare Lorentz; the related Suite from The River is also included) and Ernest Bloch’s ‘epic rhapsody’ America, a tribute to the country to which the composer had emigrated in 1916. Most interesting is the upbeat finale, ‘1926: The Present’, where Bloch seems to be taking a leaf out of Paul Whiteman’s book. Needless to say, Stokowski and his New York players are in their element.

Disc G includes the American Symphony Orchestra playing Stokowski’s moody orchestration of Scriabin’s piano Étude in C sharp minor, Op 2 No 1, proceeding to a wilful if fascinating account of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony with the same orchestra (both recordings are from 1970). Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale features some top-grade instrumentalists, not least violinist Gerald Tarack and clarinettist Charles Russo; the narrator is the French actress Madeleine Milhaud (Darius Milhaud’s wife), with baritone Martial Singher taking on the role of the Devil. The performance (from 1967) is excellent, as is an unexpectedly unfussy account of Mozart’s great Serenade in B flat for 13 wind instruments, the Gran Partita, performed by the Wind Players of the American Symphony Orchestra (1966).

Other works included are by Corelli, Vivaldi and Villa-Lobos, so if you’re after what is in effect an often spectacular-sounding selection of Stokowski’s best work in the American recording studios post-war, you’ve found it.

The recording

Complete Everest & Vanguard Recordings

Leopold Stokowski Alto (ALC3146)

Schoenberg in the US

Stokowski’s commercially recorded vintage legacy includes the first-ever complete recording of Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder (set down live with the Philadelphia Orchestra for Victor) and at least two versions of Verklärte Nacht. Both works suited the maestro’s romantic temperament, allowing him to shape both the musical line and the swelling curve of dynamics with his usual skill. Now Pristine Classical has come up with a first-ever release of a 1941 broadcast of the equally romantic tone poem Pelleas und Melisande, a Wagnerian tour de force recorded with the NBC Symphony under Stokowski during Toscanini’s leave of absence. We’re warned that ‘alas the opening bars … escaped the disc cutters and have been permanently lost – but a bit of careful editing in of a digitally-aged and -matched more recent recording has restored the missing section for this release’. Well done Pristine, but to these ears the whole performance sounds like bits edited together, with no real sense of forward momentum and a shallow sound frame that sells the work seriously short in terms of its opulent orchestration (especially at the bass end of the spectrum). So Stoky’s Pelleas is no more than an interesting curio: it tells us next to nothing about either the work or the conductor’s true view of it. But hold on, not all is lost! The Verklärte Nacht coupling, played by the Boston Symphony in 1962 when Erich Leinsdorf was named music director of the orchestra, is superb – the playing, the interpretation and a stereo recording that more or less matches anything that Victor was doing in Boston at the time. It surely justifies purchasing the disc for its own sake.

The recording

Schoenberg Pelleas und Melisande. Verklärte Nacht

Stokowski, Leinsdorf (Pristine Classical PASC724)

Rabin rarities

Last September I included in this column Parnassus’s ‘Michael Rabin on The Bell Telephone Hour’, promising a forthcoming second volume, which has now appeared and like the first includes some dazzling tracks. Both volumes are mandatory purchases for violin buffs. But more important still for fans of this great but ill-fated Ivan Galamian pupil (Rabin died from a fall in 1972 aged 35) is a coupling of two full-length concertos that he never had the chance to take into the studio, Paul Creston’s Second (which Rabin commissioned) and, most treasurable, the Beethoven Concerto. Regarding the Creston, Rabin was one of 10 musicians who received a Ford Foundation grant of $5,000 to commission a new concerto from a known composer. Creston’s work is athletic and lyrical, the lovely (even luscious) central Andante accommodating, towards its close, a sizeable cadenza, all of it brilliantly played. For the Creston, Rabin is supported by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra under Henry Sopkin (recorded 1961), whereas the Beethoven Concerto calls on the National Orchestral Association under John Barnett. Rabin’s account of Beethoven’s principal masterpiece for the violin (recorded c1960) is above all tonally pure, gliding towards the stratosphere without a hitch, with perfectly executed trills, whereas Kreisler’s first-movement cadenza is played with a rare level of intonational accuracy. Both recordings only go to illustrate Rabin’s level of musical and technical superiority while at the height of his powers. Gene Gaudette’s remastering is excellent and so are Leslie Gerber’s notes.

The recording

Beethoven. Creston Violin Concertos

Michael Rabin (Parnassus PACD96095)

A second lark ascending

In this column for September of last year I reviewed the world-premiere recording of Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending, the soloist Isolde Menges, with a studio orchestra conducted by Malcolm Sargent. ‘Granted the acoustic is rather dry for such a richly atmospheric work’, I wrote, ‘but the performance, although hardly ethereal (in the manner of, say, Hugh Bean under Adrian Boult), is a very good one.’ I could have added Jean Pougnet (also under Boult) and the work’s superb second recording (1940), reissued here, by the Boyd Neel Orchestra with the orchestra’s leader at the time Frederick Grinke as ‘soloist’ – I qualify that term because in this of all works it’s vital that the lark is a first among equals rather than too conspicuous or overbearing. VW greatly admired the recording. Grinke, a seasoned chamber player, turns in a perfect performance, his tone warmly attractive but his approach suitably laid back. Neel’s discreet accompaniment, both here and in ‘Eventide’ (from Two Hymn-Tune Preludes, which Grinke leads) suits the mood to a T, and although the recording sounds its age, Martin Haskell’s excellent transfer minimises extraneous noise without spoiling the tone of the original. Producer Ronald Grames is as accomplished in the other works programmed, namely VW’s Concerto accademico (Violin Concerto in D minor), which seems to spy the lark aloft in its expressive Adagio, and the A minor Violin Sonata of 1954 with pianist Michael Mullinar, with its 10'32" theme-and-variations finale. Here Ravel seems to be a certain influence. Arthur Benjamin partners Grinke in his Violin Sonatina, a mix of darkness and light, the happy rondo finale a real earworm. With excellent transfers and comprehensive notes by Grames, I would rate this as a significant reissue.

The recording

Vaughan Williams. A Benjamin Works with Violin

Frederick Grinke (Albion ALBCD061)