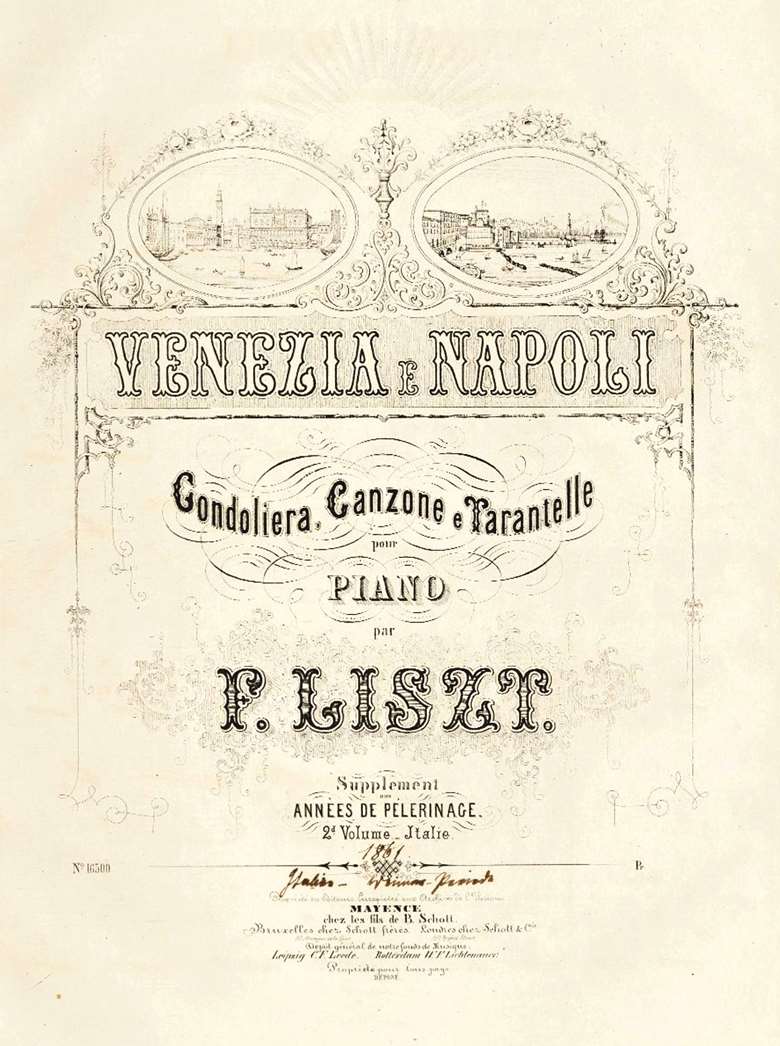

Liszt’s Venezia e Napoli: a guide to the greatest recordings

Ateş Orga

Friday, May 24, 2024

Ateş Orga introduces one of Liszt’s most picturesque works, the three-part appendix to the second volume of Années de pèlerinage that documents the composer’s travels through Italy, and surveys its glittering history on record

‘Written for the few rather than the many’, journeying vista, literature, sculpture, painting and the mystical, 26 ‘diary’ tableaux make up Liszt’s Années de pèlerinage (‘Years of pilgrimage’) series. Material of the first and second ‘years’ (‘Switzerland’ and ‘Italy’), published in 1855 and 1858, largely revised music written from the mid-1830s onwards – the Marie d’Agoult wanderlust period. Venezia e Napoli, a supplement to the second year (1859) – revisiting Italian airs he’d proofed but withheld around 1840 (S159) – appeared in 1861 (S162). Four movements comprised the 1840 text. The first, ‘Chant du gondolier’, an imposingly free-standing C minor piece in its own right, and second were omitted from the supplement, the former having been upcycled in the symphonic poem Tasso (1849-54). Recast, the third and fourth became the opening and closing numbers, Gondoliera and Tarantella. The middle movement, Canzone,was newly composed.

After a fashion, Liszt identified his sources in the supplement. I: ‘(La Riondina [Biondina] in Gondoletta) Canzone del Cavaliere Peruchini’. II: ‘(Nessùn maggior dolore) Canzone del Gondoliere (nel “Otello”) di Rossini)’. III, middle section: ‘Canzona Napolitana’. Giovanni Battista Perucchini (1784-1870) was an amateur whose ‘canzoni and barcarole in Venetian dialect became sound icons of the lagoon city, performed in the salons of Paris, Berlin, Vienna and Petersburg’ (Carlida Steffan). ‘La Biondina’ – banned by Napoleon on grounds of salaciousness – wasn’t his, though. This people’s ‘Blonde’ had history. Philadelphians in 1820 were familiar with her through Henry Smith’s ‘Where roses wild were blowing’. Beethoven, post-Waterloo, knew the song (Volkslieder, WoO157/12). A London edition of Ferdinand Paër’s Air venitien varié arrangement, c1810-16, scrolls that it was ‘sung by Madame Catalani at [her] British & foreign concerts’. Its tune and words are found in one of Jane Austen’s songbooks (mid-1790s). Even earlier, there’s an Italian transcript dating from 1782. The middle movement, with its ominous (measured) hemidemisemiquaver tremolos, quotes from Act 3 of Rossini’s opera – Dante’s ‘There is no greater sorrow than to recall in misery the time when we were happy’ (Inferno, Canto V). The Tarantella’s arabesque-variations elaborate two canzoni of the day by the Frenchman Guillaume Louis Cottrau (1797-1847), included in his Passatempi musicali (‘Musical Pastimes’), printed in Naples in 1824: ‘Lu milo muzzicato’, generating the theme, key and D flat shifts of the opening third, and ‘Fenesta vascia’ – the ‘Canzona napolitana’ of the middle section, familiar (in varied form, its first bar scalic/diatonic rather than gapped/chromaticised) from Thalberg’s 1853 L’art du chant appliqué au piano (No 24).

Liszt was rarely averse to the descriptive word. Take the leaning and drawing out of cadences in the Tarantella’s E flat canzona, each stressing and resolving the major third (G). Poco rall, he indicates nascently (bar 206), then smorzando, then in quick succession three ralls with an emphasising fermata over the last. As events blossom, so correspondingly the need for stretched dolcissimos and pauses, triggering heightened levels of imagination. Similar expressive indicators stratified the 1840 proofs. Tempo rubato cantabile sostenuto/sciolto (loose), Amorosamente (lovingly), Teneramente (tenderly), Dolce amoramente (sweet loving). The lover waits for his ‘cruel mistress’ to show at her window. The water he sells is not real but love’s tears. Pianists underestimating such expressive markers devalue the page. In both his abbreviated acoustic recording (Columbia, November 1916) and piano roll (Duo Art, December 1920), Josef Hofmann, born within Liszt’s lifetime, embodied the sentiment and expectation. Similarly Godowsky, his older Polish-American contemporary, in his (differently) truncated 1922 Brunswick, meaningful in its left-hand work. There is much to take on board: pedalling, fingering, accents, articulation, dynamics. The range of the latter is wide: fortississimo (fff)in the bravura of the Tarantella but down to pianpianississimo (pppp) for the twilight of Gondoliera, a shimmer of vibration one doesn’t always get to experience. Arrau – a grand-pupil of Liszt through his teacher Martin Krause – used to say there’s more than one way to deliberate broken chordal patterns or arpeggiate meaningfully. Equally many ways to tackle staccato, from feathered dots to scythed wedges. Pianists often finish the Tarantella abruptly, each quaver cut short. Why, one asks, since they’re actually not intended to be staccato at all, whatever Emil von Sauer might want us to believe. At speed, granted, the difference in length is minuscule but nonetheless audible as well as purposed.

Editors, inevitably, have a bearing on how pianists prepare and what listeners hear. Sauer (Peters, 1917) – still a first (if not always reliable) choice for many – and his contemporary José Vianna da Motta (Breitkopf, 1916) differed in particular over the ending of the Canzone. Vianna da Motta validated the three-bar link (57-59) added by Liszt in a lithographic reprintof the first edition (the last line re-engraved, the page in question carrying a revised plate number). Sauer excluded it, perpetrating the (indecisive) autograph’s enigmatic abruptness. In end-barring the three numbers he further dismissed that Liszt himself, in the 1861 edition, double-barred them (with a qualifying fine signing off the Tarantella), implying continuation rather than separation. In the 1859 manuscript (Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, Weimar) – Leslie Howard amplifies in his recent Urtext (Peters, 2019) – Liszt ‘even indicates the key-change across the double-barline between the Canzone and the Tarantella’. As Imre Mezo˝ and Imre Sulyok comment in the Hungarian Neue Liszt-Ausgabe (1974), the facts ‘point to the fusion of the three pieces into one work, which should be played attacca’. Performers vary in preference: concerning the Canzone most opt for the manuscript (hereafter V/i), a small few for the first edition extension (V/ii).

The earliest recordings

Complete Venezia accounts are the focus of the present survey, while acknowledging that on historical or interpretative grounds a handful of independently issued movements – from Josef Hofmann (1916) to Yundi Li (2002) – merit individual attention. The earliest audios were mechanised ‘expression’ rolls. Welte of Freiburg (Welte-Mignon) claimed that its pneumatic system, launched in 1904 – ‘a triumph of human ingenuity [seemingly] endowed with a soul’, taken up by Steinway, Bechstein, Blüthner, Ibach and Feurich – ‘automatically replayed [“reproduced”] the tempo, phrasing, dynamics and pedalling of a particular performance, and not just the notes of the music’. The Welte library included Alfred Blumen (Tarantella, 1920), Ignaz Friedman (Canzone, Tarantella, 1923) and Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler (Gondoliera, 1925). The principal American competitors, from 1913/14 onwards, were Ampico (Lhevinne’s 1929 Gondoliera) and Duo-Art (Hofmann’s 1920 Tarantella, Rudolf Ganz’s 1922 Gondoliera). A German challenger to Welte, Philipps Duca, their rolls ‘almost impossible to find’ (the late Albert Petrak), had a Tarantella in 1911 played by the Texan Wynne Belle Pyle and a Gondoliera from around 1925, cut by Rio Gebhardt, a Kurt Weill student who migrated into jazz. With Duo-Art failing in the Depression years following the Wall Street crash, Ampico’s merger with Aeolian in 1932 and the Allied bombing of Welte’s factory in 1944, the medium was defunct by the mid-Forties. Academically regarded these days, rolls bridge tradition and practice between the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As research tools, their internal documentation (ornaments, cuts, textual changes – consider Stavenhagen’s radical 1905 Liszt readings ‘as played by the composer’ – and tempo shifts) outweigh their external limitations.

In September 1941 Sigfrid Grundeis – a juror at the 1938 Concours Eugène Ysaÿe won by Gilels – recorded Venezia in Berlin, his Odeon blue being the only complete version listed in The World’s Encyclopaedia of Recorded Music (1952). Previously the Glaswegian Germanophile Frederic Lamond, a pupil of Liszt in Weimar, Rome and London – his contemporaries, class of ’85, including Stavenhagen and Vianna da Motta – recorded the Tarantella in London in February 1929, aged 61 (Studio C, Small Queen’s Hall; APR). Glosses catch the ear in the canzona – the crisp near-double-dotted rhythms of the melody, the Bebung-like repetitions fluttering the melodic G of the first poco rall (bar 206), the added trill in 262, anticipating Liszt’s four bars later. Elsewhere mishits and variable coordination detract, Lionel Salter’s generality springing to mind: ‘An “innocent ear” listener knowing nothing of him and his reputation might well class him as a quite good, but certainly not great, pianist’ (Gramophone, February 1995). A much-lauded Lisztian grandee but Northern cool more than Southern warm.

Edward Kilényi – trained in Budapest by Dohnányi – was for Beecham ‘the true successor of the great Romantics’. A 1938 Pathé 78 of the Tarantella suggests the layered voicing of its canzona but breathlessly agitates the outer sections. (Sub-eight minute performances of this minefield usually come at a cost, Kissin being the exception.) Gondoliera sings only fitfully. Julian von Károlyi’s longer Tarantella (two versions, 1943, 1949) is more of a poised poem, iridescent in its placed chromatic wraiths, a probingly musical ‘modern’ reading. Louis Kentner – pupil of Kodály, friend of Bartók, fifth to von Károlyi’s ninth and Alexander Uninsky’s ‘toss of the coin’ first at the 1932 Chopin Competition – was a keyboard grand seigneur who with Sacheverell Sitwell and Humphrey Searle championed Liszt in post-war Britain, his BBC broadcasts required listening, his company, erudition and sensibility a privilege to know. He first recorded Gondoliera and the Tarantella in March 1938 (reissued on APR, Naxos and Profil). ‘The appalling difficulties of the [latter] leave the player neither paralysed nor struck down with tetanus’, reported Gramophone six months later. ‘Those who like the art of the virtuoso from a sporting aspect will have a grand time hearing him take his fences … triumphant and unwearied.’ Timing, tone, touch, fioritura, clarity of speech, projection and connoisseurdom hallmarked his style. At nearly six minutes, Gondoliera is luminous, a faded photograph of distant stars and reflected lanterns. The Tarantella takes a poised 10. Twenty-five years on an HMV remake followed. Drawn to intellectual Liszt, the bespectacled young Alfred Brendel had little in common with post-war Kentner when it came to Latin dance. Engineered (poorly) in Vienna for Vox, released in 1959, his bullish handling of the Tarantella’s flanking sections, the hard clatter of ornamentation in the canzona (the long silence beforehand dislocating it into almost a separate movement),show it just wasn’t his kind of music, any more than it wasn’t Arrau’s.

Views from the East

The Fifties and Sixties saw trilogies in ascendancy. Lajos Hernádi studied with Bartók, Schnabel and Dohnányi, and in a pedagogically distinguished career at the Liszt Academy in Budapest taught Tamás Vásáry and Peter Frankl. The lyrical, rhetorical aspects of his 1956 Venezia fare best, a heavy-action, stiff-sounding instrument impeding flow and lightness of articulation elsewhere. With Khrushchev’s thaw easing the political climate, Sviatoslav Richter took Europe, then America, by storm. Critics – most, not all – concurred. ‘Such was the delicacy and subtlety of his art that the merest swell from a pianissimo to a piano signified more than many a rival’s fortissimo fuoco’ (Joan Chissell). Emphatically an organic, ‘double-barred’ whole, Canzone V/i notwithstanding (curiously, since Yakov Milstein’s 1952 edition incorporating V/ii was available to Muscovites), he recorded Venezia during a recital in the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory on 2 March 1956. Its poetry, dynamic range and boundless facility, the sense of panorama, are tangible.

Soviet pianists before and after Richter, Gilels apart (and he left Venezia alone), were an esoteric breed in the post-war West, their recordings near impossible to find but essential to hear. Grigory Ginzburg, born in 1904, a pianist fast in youth, measured in maturity, believed, quoting the Nobel Prize-winner Ivan Pavlov, that ‘art, just like science, demands the whole of a person’s life … be passionate in your work and your searchings’. A committed Lisztian, he entrusted nothing to chance: listen to the sweep and supremacy of his Gondolieraand Tarantella shellacs (Moscow, 1948). Berta Marants, slightly younger and a student of Neuhaus, the ‘adornment of his school’, possessed an exceptional armoury. An archive recording of the Tarantella reveals strong temperament and tone, the demands of the piece, physical and poetic, no obstacle. Lost to history, Tatiana Ryumina, born in 1950 and in Flier’s class at the Moscow Conservatory, disappeared shortly after reaching the finals of the 1974 Tchaikovsky Competition (an accident ending her career, some said). On what limited evidence there is, she was a fearless player, flying the high wire. Her Tarantella canzona, an early-Seventies broadcast, rewards.

A 1998 American Tarantella from Goldenweiser’s Kyiv-born student Dmitry Paperno – Rostropovich’s ‘curator of the honey of our youth’ – is worth seeking out. When it comes to super-drilled dexterity, modern Russians – home-rooted or expat – seldom disappoint. Yet, too often, one wonders where the fantasy has gone. Ksenia Nosikova’s Venezia (2001) holds out hope. Boris Berezovsky’s casual run-through at the 2009 Festival International de Piano de La Roque d’Anthéron (Mezzo/YouTube) offers Canzone V/ii but the speed, matter-of-factness and neglect of tone in the Tarantella bodes ill. Another performance two months earlier at the Festival de la Grange de Meslay (Mirare) wasn’t significantly better, still with a sub-eight minute Tarantella. Less thespian, more B-movie support actor.

‘Phrasing in music is like speaking or reading, observing punctuation marks, and dynamics are like voice inflection. Don’t overdo or underdo either.’ A late Egon Petri performance (?1960/1962) injects vitalised strength and energy – private, personal and musing, playing with silence, time and articulation, structure and fantasy to the fore, dexterity and tone unimpeded. The end of Gondoliera urges then relaxes; Canzone draws the curtain back on tragic operatic theatre; the Tarantella is wild, roaring its climaxes, a dialogue of aria and pulsed bass tones, gesture before hush, two extra bars of harmonic hum initially, comprising the central core. Forget the slips and distortion, here is a lordly elder statesman caught on the wing, not a hint of frailty or demise in the air. ‘I know all the rules, but if the rules don’t fit, I break the rules rather than break the music.’ Others of the day included Gunnar Johansen, the Leslie Howard of his era, powered with ‘the physical stamina of a Viking’ (Frank Cooper), whose budget-end Blue Mounds Liszt project, harshly engineered, was a grail-seeking 53-volume exercise (available on YouTube). Rough stitching (Tarantella) yet not without moments to haunt the night (Gondoliera). More winning was Edith Farnadi (HMV or Westminster LPs), a technically replete Hungarian whose teachers included Bartók and who liked to find the music in Liszt’s sighs, hesitations and silences. France Clidat in 1968 proved more rattler than seducer of notes. Jerome Rose’s Venezia five years later was sturdy if a shade ordinary, similarly not that disposed to probe or ‘speak’.

Two Italians in Paris’s Salle Wagram occupied a league of their own. With limpid note repetitions and an interesting way of accenting Liszt’s harmonically pungent left-hand acciaccaturas in the Tarantella, Sergio Fiorentino’s sense of scale, character and expressive warmth was keenly gauged in September 1962. Gondoleria (almost six minutes, cf Kentner) is a morning-mist watercolour, wistfully calling in its major sixths. Little wonder Michelangeli and Horowitz admired him. Aldo Ciccolini’s September 1969 interpretation is bronzed and aesthetically refined, fusing incisive pianism, glowing imagery and demonstration piano sound. His rhythmic perception and tensioned attack – every note meaningfully placed, toned and coloured, textures clear and suggestively voiced, songs and bells in dreamy marriage – make for a breathed, eloquent, virile cocktail. Further, he opted for the Canzone’s V/ii ending. No attaccas, true (invasive post-production?), but an enduring masterclass, regal in touch. Similarly Wilhelm Kempff’s lone 1974 Gondoliera (DG), its luminous die-away cherishing F sharp major Liszt, the incense wafting more than smothering.

Berman and Cziffra galvanised the Seventies. Not, though, before a rash seven-minute Tarantella from John Ogdon (RCA, Tokyo 1972). Lazar Berman was ‘a bear of a man … like a character actor in a Chekhov play’ (The Times) – ‘a great believer’, his Bulgarian-born disciple Nadejda Vlaeva remembers, ‘in the importance of silence and the place it had in music … he’d warn that speed and rushing should not be confused’. Venezia e Napoli was core repertory for him: he first recorded it in London in 1958, shortly before his B minor Sonata for Saga. His May 1977 Munich taping has appeal yet a touch too much carefulness, the measured tempo, pauses and held-back leanings of Gondoliera and (especially) the canzona bordering on mannerism. Preferable was his Melodiya version two years previously. Spiralling technique, ‘pouring sonic diamonds out of his sleeve’ (Liszt’s rapid 4-3-2-1 finger-changes glittering), pricked ‘Fiorentino’ accents, manly emotion, adrenalin climaxes and a wonderfully spun rallentando-intensive canzona inhabiting the mountain lands of high Affekt are all to be savoured. A film of his Tokyo Bunka Kaikan recital in January 1988, even more acute accents spicing the Tarantella, shows him garnering long-honed elements from the ’75/’77 studio visits. ‘The greatest swashbuckler of them all’, Bryce Morrison deemed Georges Cziffra (Gramophone,March 1995). Venezia – from his Années cycle, mostly recorded in Paris between September 1975 and May 1976 – is a ‘cannons and flowers’ affair, free and feral. Surprises capricious and profound abound. Gondoliera wakens thoughtfully. Canzone, V/ii no less, sorrows dolorously in its subterranean rumbles and triple-dotted rhythms. The Tarantella dances with Romani fires andboudoir ravishment – shifting tempos, sensually reinforcing lower registers, adding octaves and generally teasing. An earlier version, released in 1963, is mercurial, those repeated notes lighter still. Trauma of the decade (though, not released until 2017, it had yet to dawn on us) was the ‘gargantuanly bizarre’ Hungary-to-Hollywood, riches-to-rags spectre of Ervin Nyíregyházi at the Century Club of California in December 1972. His Tarantella left hand was a maelstrom of ocean breakers, cyclonically ‘orchestrating’ the canzona (as well as prolonging its opening à la Petri), the whole climaxing in a pugilistic earthquake of jangling dynamics, shattered chords and splintered notes, neither audience nor piano with anywhere to go.

The modern era

One of the anticipations of the early Eighties was Jorge Bolet at Kingsway Hall, 19-22 October 1983 – among the last Decca sessions from that temple to sound. His allegretto slant on Gondoliera is briskish, contemplation only creeping in during the last page or so. Canzone is declamatory, leading directly into an upfront, measured Tarantella. This is a serioso reading, big on pianism (and forward microphoning). But, expressively, it’s on chilly side, more hedgerow frosts than ‘wine dark sea’. If you want flame and personality, less constraint, ‘flexibility within the pulse of the music’, Bolet on stage, physically daunting, Bechstein in full cry, then listen on YouTube to a Dutch radio broadcast from Utrecht days later (29 October). A thrilling adrenalin-fuelled fest, responding to moment and sentiment with time for foxed-mirror images, before us a man reminiscing a youth apprenticed to Godowsky-Hofmann-Saperton-Rosenthal. Of the same generation but younger – Juilliard rather than Indiana/Curtis associated, Vengerova-Samaroff-Kapell-Steuermann-Cortot polished – Jerome Lowenthal, surprisingly, didn’t release Venezia (Canzone V/ii) until pushing 80 in 2010. Contrasting his compatriot Jeffrey Swann’s pacy 1989 Italian cover, it’s a classy achievement, reminiscent of the big-boned approach of studio Bolet but with fuller heart and more yielding touch. Stirring memories of Terence Judd, the old soul the gods loved too much, Norma Fisher’s 1985 BBC Venezia (released in 2019) sailed a graciously cultured voyage of cypress-shaded languor, coloratura projection and vernal sap – Russified Lithuanian-Polish-Jewish/German ancestry somewhere indefinably in the mix. A couple of years later, Stephen Hough, pre-Hyperion, gifted us a vintage stand-alone Tarantella (Henry Wood Hall) – a sensitively graded reading with individual touches (the near-cessation rallentando, bars 156-57).

Leslie Howard launched his hundred-CD Hyperion Liszt edition in the mid-Eighties, laying down two versions of Venezia in 1992 (S159) and 1996 (S162). S162, at 19 minutes, is not without competitive edge, proffering a leisured Gondoliera, the inclusion of Canzone V/ii and a Tarantella racing the furlongs yet with time to negotiate finger-twisting nightmares. S159, though, makes a lesser impression, catching something of the gravitas of the Tasso opening but with a third movement that lacks composure and an against-the-clock finale bent on getting the notes down. For Naxos’s Liszt series, Jue Wang (winner of the Maria Canals and Paloma O’Shea Santander competitions) is superior, his Tarantelles napolitaines flattering Liszt’s imperfect design, making more musical sense at 11 minutes than nine. Jenő Jandó, stalwart of the Naxos catalogue in its foundation days, entered the arena in Budapest in 1991. His 16-minute survey is crisp, clean and commendable, on the brisk side maybe but neither ordinary in spirit nor display-centric. A reliable, technically assured choice breathing musicality, he features Canzone V/ii as well. So too, more menacingly, does his technically consummate French-based compatriot Irène Polya – her pedigree emanating from Hernádi, Kurtág, Lefébure and Nikolayeva – who in the same year scaled the peaks in a commodious performance marrying the Grand Manner with modern sensibilities channelled through an aristocratically voiced instrument. In recital, reissued in 1996 from a December 1977 concert in Pécs, the phenomenal Zoltán Kocsis built edifices and alcoves, echt magyarok in nuance, allowing himself tears in the E flat fragility of Canzone (maggiore whitening minor) and the Tarantella, his rubato and sad dreaming in the latter persuading more than Berman’s ruminations months earlier, the line better sustained. An attacca version by Frederic Chiu (2000, Canzone V/ii) has brillante points, theatrical gestures and expressive respites but transient foibles prevent it entirely meshing.

The most recent recordings

‘Play the right key with the right finger,’ Ganz, invoking Liszt, was fond of saying, ‘the right finger, the right tone and the right intention – that’s all!’ Prodigious modern Venezias abound. Leading the field in the Liszt bicentenary year, 2011, were the Canadian ‘Ramillies/Resolution’ big guns Marc-André Hamelin and Louis Lortie, recorded in England the year before (Henry Wood Hall, Potton Hall). Both excel in different ways. With Lortie (broader than his 1995 Port-Royal release) you get greater resonance and bass end. A bewitching painter (those tricky-to-balance black-note triads at the end of Gondoliera glowing in sepulchral light), he drapes the Tarantella’s central heart in stained-glass nostalgia. With Hamelin (who recreated his performance at the 2011 Proms) you get more physical clarity (less open pedalling) and a Tarantella sharper in its outer sections. Neither plays the cadential extension in Canzone V/ii; nor Alexander Krichel. Michael Korstick and Sinae Lee do. Bertrand Chamayou also, in a high-octane, blue-blood reading of Venezia no one should miss. Watch his Mezzo telecast, visceral and in-the-moment. Attracted, like Mūza Rubackytė, to an alternative Canzone solution, Nicholas Angelich takes time with the Tarantella, doing beautiful things with the canzona, conceiving a performance that, paraphrasing Liszt, ‘has other uses than the beguiling of idle hours [or] the futile distraction of a passing entertainment’. In similar vein, Nadejda Vlaeva’s fine-wine Venezia is about grace and perception, her Gondoliera unassumingly alert to the fact that the music opens on the off-beat, an aspect Ragna Schirmer, a poet in reflective moments, also communicates tellingly. Similarly Benjamin Grosvenor (Wyastone Concert Hall, December 2015), a pianist trading on physical contrasts and beautiful sound (Gondoliera), crystalline technique and ‘cinematic melodrama’ (Dominy Clements). Despite an arguably passé reversion to Canzone V/i, his is an attacca,conscientiously crafted, groomed overview. From Timişoara, Suzana Bartal studied with Frankl at Yale. In Lisztian spirit she curves to climaxes and protracts cadences, and in a French priory acoustic très ancien she mines the sonority and power of her Steinway from deep recesses. Trills and arpeggiations have shape and meaning, grace notes speak and pedalling is as rich or secco as contexts demand. Canzone V/ii evokes. The central pages of Tarantella float like rays of sunset.

For a century and a half Gondoliera and Tarantella have lent themselves to stand-alone programming, understandably given their nocturne/showcase parameters. Among post-2000 Tarantella front-runners, the Ukrainian Alexander Gavrylyuk (Piano Classics), Gold Medallist at the 2005 Arthur Rubinstein Piano Masters in Tel Aviv, impresses with his command, imagination and keyboard finesse. Another Ukrainian, London-based Vitaly Pisarenko, winner of the 2008 Utrecht Liszt Competition, is enriching too, penetrating comprehensively. Mariam Batsashvili, a former BBC New Generation Artist, unfolds a different story. Every fibre of her being, like Bartal’s, depends on Liszt. A videoed Tarantella from the Gyeonggi Arts Center (2015, available on YouTube) may not be the tidiest but its chemistry, the adrenalin rush, her body language, is knife-edge stuff, the ‘thrown’ chest-voice projection of the canzona oddly bringing to mind Erich Kleiber’s trumpet-gilded inter-war Berlin 78s of Karl Müller-Berghaus’s 1883 orchestration. China’s refined, modulated Yundi Li impresses with a high-status Berlin Teldex reading (DG, 2002).

‘Touch’, Amy Fay wrote in The Etude (May 1902), is such ‘a wonderful and subtle thing, [revealing] the whole personality of the musician in a most mysterious way’. Liszt performance has long been dogged by temporal and stylistic issues, infiltrated more and more by pyrotechnicians intent on Olympic targets. Sauer used to fret that ‘Liszt wouldn’t recognise his music as it is usually played today … piano-playing now is too loud and too fast’ – for which Rosenthal, Godowsky and the four-minute 78 must in part have been responsible. A few years ago Brendel worried that ‘much of Liszt’s music is nowadays played at overheated speeds. The last thing Liszt deserves is bravura for its own sake. Likewise, he should be shielded from anything that sounds perfumed.’ Bolet was of the opinion that ‘speed is the enemy of excitement’. Auditioning more than a hundred Venezia pianists, 16 or thereabouts make a provisional shortlist: Bartal, Berman (1975), Chamayou, Ciccolini, Cziffra (1963, 1975/76), Fiorentino, Fisher, Grosvenor, Hamelin, Jandó, Kocsis, Lortie, Lowenthal, Polya, Richter, Vlaeva. Aloft among the halcyon legends: Fiorentino and Berman. Desert island companion? Bertrand Chamayou.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of International Piano. Never miss an issue – subscribe today