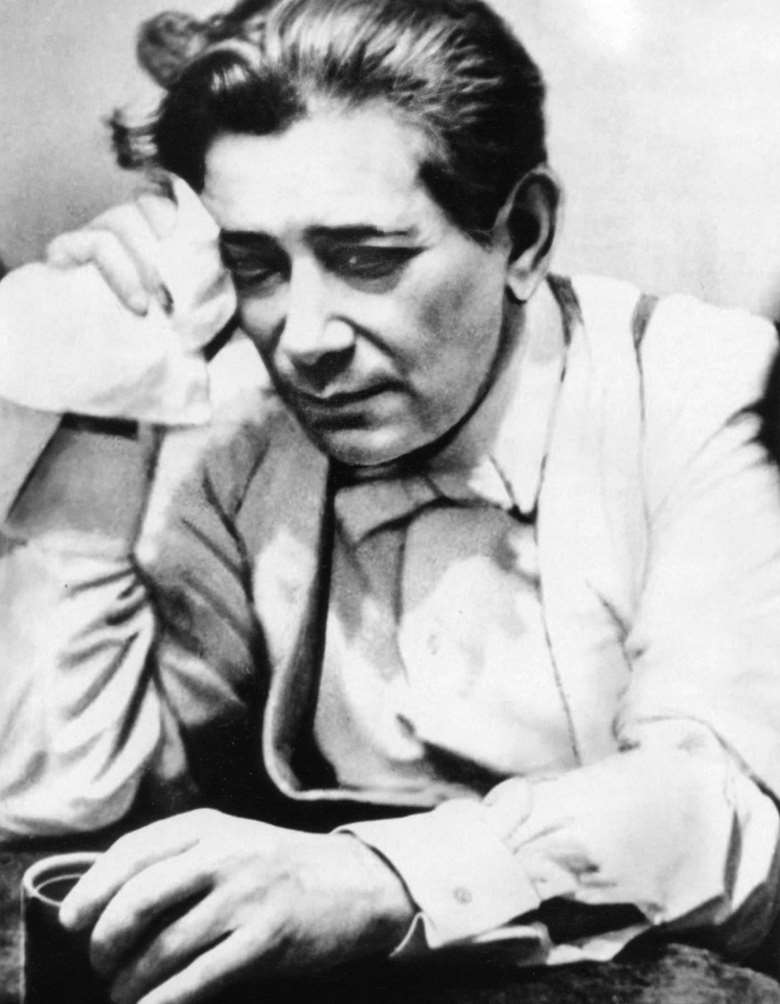

Grigory Ginzburg: a refined virtuoso

Farhan Malik

Friday, May 24, 2024

In his latest exploration of the life and playing of great Russian pianists of the 20th century, Farhan Malik investigates the astounding pianism of Grigory Ginzburg and celebrates a lasting legacy

In the annals of Soviet pianism, three great artists in particular stand out for the disparity between their artistic stature within their native Russia and the almost complete lack of awareness of their existence outside of the Eastern bloc. The first two of these, Vladimir Sofronitsky and Samuil Feinberg, are finally receiving their due recognition, but the third member of this triumvirate, Grigory Ginzburg, remains the least known and in many ways the most misunderstood of these great artists.

Grigory Ginzburg was born on 29 May 1904 in Nizhny Novgorod, which lies at the confluence of the Volga and Oka rivers about 400km east of Moscow. His parents noticed his unusual affinity for music and started him on the piano at the age of five. ‘Already when I was five, I liked to spend time and play by ear what my older brother played. Everybody was shocked by that,’ Ginzburg recalled. He progressed so rapidly that the following year they took him to play for the renowned pianist and pedagogue Alexander Goldenweiser at the Moscow Conservatory. Ginzburg was accepted as a student by Goldenweiser, who put his wife Anna in charge of the child’s early pianistic development. Tragedy struck a year later. Ginzburg’s father died unexpectedly, leaving the family in dire financial straits. Goldenweiser offered to take him in, and so the young boy continued his studies while living with the Goldenweisers. One advantage of living with such an illustrious figure was the circle of friends and colleagues who frequently visited. During those formative years, Ginzburg met and heard Rachmaninov, Medtner, Scriabin, Blumenfeld and many other important musical figures.

He often made the front page of newspapers and was compared not unfavourably to Cortot, Hofmann and Rachmaninov

It was during these years that Ginzburg built up his legendary piano technique. Although Anna Goldenweiser was his main teacher, her illustrious husband also worked with the boy. ‘He gave me fantastic technical preparation. I played all kinds of scales with different accents and rhythmic patterns. I really knew all 60 Hanon exercises in all keys and I could play each one perfectly,’ Ginzburg later said of his studies with Goldenweiser.

In 1916 Ginzburg formally entered the Moscow Conservatory. As he recalled, ‘they considered me a prodigy, especially in technique’. His work with Goldenweiser continued: ‘I played Czerny’s Op 299 [The School of Velocity] and Op 740 [The Art of Finger Dexterity] … Absolute accuracy was required. Goldenweiser could come in the room at any time and check. He was very thorough with me and generous with his time. Sometimes it was very difficult. One time he got mad and threw all my notebooks out the window from the fifth floor and I had to run and get them.’

In 1924 Ginzburg graduated from the Moscow Conservatory with a gold medal. In the Conservatory he had been a star, always praised, but after graduating things didn’t come easily to him. For the first time in his life his playing was criticised, and as he had no management he found it difficult to get concert engagements. Ginzburg began to feel dissatisfied with his playing and technique, and finally decided that a full re-evaluation was in order. Although this was a difficult realisation for the young pianist, he later stated that had this not happened he never would have developed into the pianist he became.

A turning point in Ginzburg’s career occurred in 1927. He was selected to compete in the First International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw, where he won fourth prize (his countryman Lev Oborin took first). Following that success, his career took off. A wildly successful tour of Poland quickly followed. More and more engagements came, including an invitation to tour America, and critics were universally enthusiastic about the playing of this young virtuoso. Interestingly, in the midst of all this, he received a letter from Anna Goldenweiser in which she expressed fear that this success might change him for the worse. ‘Never feel that the quality of your performance is measured by external success, which is so capricious … Please don’t misunderstand me, I know more than anyone what you are worth … No matter what they say and no matter how they shout, you yourself should know better than anyone what the truth is.’ Ginzburg took this advice to heart and decided to return to Russia. He turned down numerous engagements, including the USA tour, so that he could finish his studies, continue to improve his playing and learn more repertoire.

Despite adding works by Brahms, Schumann, Ravel and Scriabin (all of the Op 8 Études) to his repertoire, as well as various transcriptions, Ginzburg continued to be associated most of all with the music of Chopin and Liszt. Critics singled out his exceptional virtuosity, finding him an ideal interpreter of Liszt. In the 1930s he further expanded his repertoire with works by Beethoven, Mozart and, surprisingly, Kabalevsky, a contemporary composer whose music he particularly enjoyed. In 1936 he toured Sweden, the Baltic countries and Poland again. His success was overwhelming everywhere he played. He often made the front page of newspapers and was compared not unfavourably to Cortot, Hofmann and Rachmaninov, who were also touring Poland at that same time. However, the demands of such an intense touring schedule took their toll. ‘During 12 days [in Poland] I played 10 concerts,’ he recalled. ‘I hardly slept a single night because I was travelling all the time.’ Despite the exuberant reviews and ecstatic public reception, Ginzburg again began to have self-doubts. There was never time to develop his artistry and he became more and more dissatisfied with his playing. Adding to his workload, he had accepted a position at the Moscow Conservatory in 1932, and he was frequently invited to sit on piano competition juries.

Ginzburg’s Chopin is highly refined and elegant with tasteful but expressive rubato

Over the next five years, Ginzburg maintained a busy schedule, but also worked on his art. It was the beginning of a transformation in his playing towards a more mature style that penetrated deeper into the music’s meaning. Works by Beethoven started to feature more often in Ginzburg’s programmes: whereas in 1936 he played a series of concerts devoted to Liszt’s music, on 14 May 1940 he played an all-Beethoven programme for the first time. In the past, with few exceptions, he had avoided playing chamber music, but he began to add this increasingly to his activities. Such a transformation was difficult for the critics to grasp, as virtuosos are typically typecast as not being deeply penetrating musicians or sensitive collaborators. This was an issue that plagued him for the rest of his life, and even today he is often described as a virtuoso who excelled in Liszt rather than the well-rounded, fine musician he actually was. As one critic wrote, with a note of surprise: ‘Ginzburg is a brilliant virtuoso. But at the same time, he is also a subtle chamber musician.’

Any hopes Ginzburg had of touring outside of the Soviet Union were dashed by the outbreak of the Second World War. During the war Ginzburg was kept extremely busy. He taught not only his own students but also those of Lev Oborin when the latter was on tour. Ginzburg’s own concert tours within Russia continued, and he also played numerous times for soldiers and for the radio. ‘Today I play at 2, 6, and 9pm on the radio … I am very tired … the radio always orders new things and I never refuse anything.’ When the war ended, Ginzburg’s activities ramped up even further with over 100 concerts a year and frequent trips to the recording studio. He also got more interested in Russian repertoire and added many works by Tchaikovsky, Arensky, Anton Rubinstein, Scriabin, Borodin, Balakirev, Glinka and Medtner to his repertoire. In the late 1940s Ginzburg became increasingly interested in the music of Mozart. ‘When I was younger I loved the Romantics and was scared of the Classics. When I was older it was the reverse … When I play Mozart I feel every note. I breathe this music. There is a real creative joy when you feel you have discovered the composer’s hidden treasures.’ The one composer conspicuously missing from his programmes (not just then but throughout his career) was Rachmaninov. His reason for this was simple. He idolised Rachmaninov but could not imagine playing this music better than the composer himself – although it should be noted that he did play Rachmaninov’s Suites for two pianos several times during his career.

Ginzburg was never in favour with the ruling Communists, but in 1956 the regime finally allowed him to leave the Soviet Union to perform in Hungary. After huge success there, he was allowed to tour Czechoslovakia in 1959. His concerts were received so enthusiastically that further foreign tours and engagements were planned. There was great optimism for the future, but health issues tragically interfered with those plans. In May 1960 he suffered a heart attack and spent two months in hospital. After regaining his strength he resumed playing concerts, and was able to tour Yugoslavia in early 1961. Those concerts were also a resounding success, but Ginzburg’s health was in serious decline. He had been diagnosed with an untreatable cancer, and by August 1961 it became clear that the end was near. On 10 November 1961 Goldenweiser, who was also very ill at the time, sent him a deeply touching letter: ‘Dear Grisha … I love you so much that I fell ill together with you … Unfortunately your illness seems more serious than mine … Get well soon! I think about you all the time. I love you very much like a dear son. Your old (very old) A Goldenweiser.’ On 26 November Goldenweiser died. His student, Grigory Ginzburg, followed nine days later, on 5 December 1961.

Ginzburg’s death was a huge loss to the music world, but his legacy lives on through his brilliant transcriptions, his many students and his wonderful recordings. From his earliest days of concert-giving, Ginzburg often included transcriptions by Liszt, Busoni, Godowsky and others in his programmes. His virtuoso renditions would drive his audience into a frenzy. This fascination with transcriptions led to his creating his own. The most famous of these is of Figaro’s cavatina from Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia, which is still played today by a few pianists. He also transcribed Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite, Kreisler’s Praeludium and Allegro (in the style of Pugnani), Róz˙ycki’s Casanova waltz and Rakov’s Russian Song. The sheet music for all of these is available in a beautiful edition from the Jurgenson publishing house in Moscow.

As a professor for nearly three decades at the Moscow Conservatory, Ginzburg taught many students who went on to have successful careers. The pianist Gleb Axelrod is widely considered to be his greatest student. Although Axelrod is barely known in the West, he taught for many years at the Moscow Conservatory, and his recordings for Melodiya show him to have been a formidable pianist. Another student, Sergei Dorensky, became a legendary teacher in his own right, whose students include Nikolai Lugansky, Denis Matsuev and Olga Kern. Sulamita Aronovsky, another Ginzburg pupil, was for years one of the most sought-after piano teachers in England.

We are fortunate that Ginzburg left several hours of recordings for posterity. His recordings are consistently of a very high level, which is in no small part due to the fact that he enjoyed the process of making them. His recordings of Liszt’s Norma and Don Juan opera paraphrases, the Mozart/Liszt/Busoni Figaro Fantasy and the Tchaikovsky/Pabst Polonaise from Eugene Onegin are legendary. Although the virtuosic ease of the playing is what initially leaves one awestruck, the overall musicianship and ability to let the works unfold are equally impressive. He also made excellent recordings of various transcriptions by Godowsky, Galston and Tausig, his own Rossini transcription, several Schubert/Liszt songs and four of Liszt’s Paganini Études. These acclaimed recordings have always been a double-edged sword, since as fine as they were they have overshadowed his accomplishments in other areas of more ‘serious’ repertoire. For example, his recordings of Mozart’s A minor Piano Sonata, K310, and C major Piano Concerto, K503, rank among the finest recorded versions of these works yet they are nowhere near as well-known.

One of the greatest accomplishments an artist can achieve is to perform a work so convincingly that it redefines how the piece is perceived. With his recording of Tchaikovsky’s Grand Sonata in G major, Op 37, Ginzburg did exactly that. This work is generally considered rather weak and has never really entered the canon of the piano literature. Sviatoslav Richter’s over-aggressive recording of it has not helped its case. In Ginzburg’s hands, however, the sonata reveals itself to be a masterpiece. Unlike Richter, Ginzburg’s approach is lyrical and expressive throughout, full of fantasy, and he plays with such emotional intensity that one cannot help but be deeply touched. Perhaps if more people knew Ginzburg’s version the reputation of this work would be rescued.

Chopin’s works were a major part of Ginzburg’s repertoire and fortunately he left many Chopin recordings. Ginzburg’s Chopin is highly refined and elegant with tasteful but expressive rubato. Perhaps there has never been such a pristine, musically sincere rendition of Chopin’s Op 25 Études. The mazurkas and impromptus he recorded are poetic gems. Surprisingly, his Fourth Ballade is a rare disappointment – it’s so refined that it ultimately lacks the fire and passion necessary for the work to succeed.

Ginzburg’s discography also includes individual works by Arensky, Gershwin, Medtner, Myaskovsky, Prokofiev, Rubinstein and Schumann. A great starting place for those new to this pianist is his volume in the Philips ‘Great Pianists of the 20th Century’ collection. The contents of that volume were put together by the pianist’s son, and it includes his Tchaikovsky Sonata among other works. His disc in BMG/Melodiya’s ‘Russian Piano School’ is also a good starting point as it contains his phenomenal recordings of opera transcriptions. In the mid-2000s, the label Vox/Aeterna issued a series of live recordings from the Ginzburg family’s personal archives. With these, one can finally hear Ginzburg in major works that were new to his discography, including Beethoven’s Appassionata, the Bach/Busoni Chaconne, both Liszt concertos and Ravel’s Sonatine. Finally, a series of discs on the defunct Arlecchino label remains the most comprehensive reissue of his recordings to date and they are definitely worth acquiring if they can be found.

Grigory Ginzburg was held in the highest esteem by both the public and his colleagues. Though he is even today thought of as mainly a virtuoso, he was much more than that. Leonid Kogan, with whom he played many recitals and recorded several violin sonatas, remembered him as ‘this wonderful, amazing artist who lived among us, whom we all loved infinitely – one of the greatest pianists of our time.’ Fellow Goldenweiser pupil Tatiana Nikolayeva said that ‘the penetration and depth of his playing was worthy of the highest praise. He was a true artist, still undervalued.’ Ginzburg’s older colleague Samuil Feinberg lamented ‘the untimely death of one of the most remarkable pianists of our time’. Perhaps Yakov Flier put it best when he wrote ‘there are such people where the soul cannot reconcile for a very long time that this person is no longer there’.

Many biographical details found in this article were sourced from the Russian book Grigory Ginzburg: Essays, Reminiscences, and Writings (Moscow, 1984). The author also wishes to thank Dmitry Rachmanov for sharing his research on Ginzburg’s career.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of International Piano. Never miss an issue – subscribe today