Working with Pavarotti: demands, differences & riveting results

Michael Haas

Wednesday, July 3, 2019

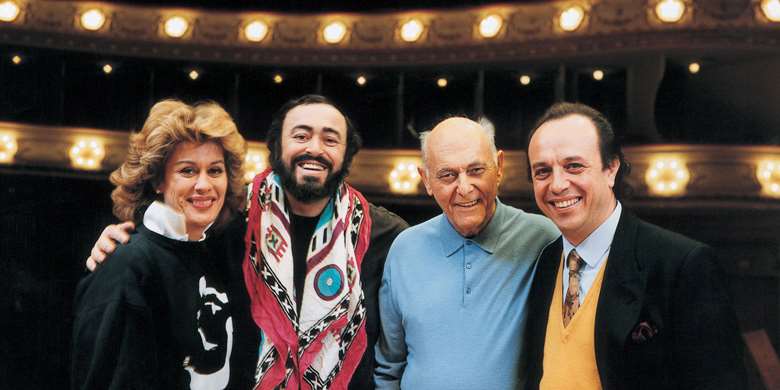

Recording Pavarotti in Otello meant balancing his very specific views with Sir Georg Solti’s often completely opposing ones, recalls producer Michael Haas – but the results were well worth it

The call came at 8am as it did every morning while we were rehearsing and recording in New York: ‘Michael! This is Herbert Breslin. Luciano says he isn’t going to sing tonight if …’ There then followed a litany of caveats: the lights – they shouldn’t be bright enough to allow the audience to follow the libretto (of which Pavarotti disapproved), and the question of when they should actually go up (there was a request for the tenor to enter the stage in pitch darkness so that nobody could see him squeeze past the orchestral players); and the order in which the soloists entered the auditorium – Pavarotti was too large to enter gracefully, and being flanked by more elegant and sprightly singers would only highlight this fact.

I was the recording producer placed in a booth in the basement and absolutely none of this had anything to do with me. Actually, it mostly had to do with the Frankenstein’s monster that Pavarotti’s manager, Breslin, had created. It was only one of very many issues during the making of Otello that indicated the utter stressfulness of any project involving Big Lucy.

And this recording, as the ‘farewell’ event for Sir Georg Solti after 22 years as Music Director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, was already stressful enough! The event was as high profile as it could be, with performances of Otello scheduled to be recorded live, first in Chicago then at Carnegie Hall in New York: different venues, different acoustics, different publics. Pavarotti had already surpassed the acceptably decent sales figures of a successful classical artist, and he supposedly vulgarised classical by going on to outsell many a pop star – to the great and good of the day, this was unforgivable. He was also making a number of people very, very rich. With piles of money came the stress and expectation that it might just all go horribly wrong.

‘Every ensemble, according to Pavarotti, was a tenor aria with everyone else an obbligato in the background’

I had forgotten how generally positive Alan Blyth’s Gramophone review of the recording in November 1991 is. As ever, there are shades of condescension, with references to historic recordings that would inevitably appeal owing to their proximity to the first performances. It was hopeless to compare a modern recording (even a live one) with the stage-crafted performances of an age when opera was more theatre than music. The post-war recording industry had driven opera into the studio, and that came with unexpected artistic costs. If the voice could be recorded, who cared if the singer couldn’t, or wouldn’t, act? They were in an environment where nobody could see them and you could create your own image in your mind while listening. The theory was good, but in practice, opera recordings had become dramaturgically lazy: panoplies of slightly disembodied and disconnected lovely voices. And yet, Pavarotti was somehow different. His genius with the Italian language was an art form in itself. Nobody could act so completely with only his voice. It was not just the ability to pronounce every consonant and vowel clearly, it was the ability to characterise them with a vibrancy that left most other singers of his generation blindsided, including his devoted Dame Joan Sutherland.

In theory, Pavarotti was both everything wrong and everything right with modern opera recording. He was wrong because, quite frankly, on stage he was unable to bring body and voice into dramatic harmony. He was perfect in the studio, where he more than compensated for what he lost on stage. There are many singers with perfect ‘recording voices’, but very few of them could also spit out such dramatic characterisations as he did from behind the safety of the microphone.

My first encounter with Solti was coincidentally enough during Decca’s recording of Otello in 1977 at Vienna’s Sofiensaal, where I was musical assistant. It was with Carlo Cossutta and Margaret Price. Solti was terrifying, and Price was captivating. My first encounter with Pavarotti was a couple of years later as Decca’s studio producer on Riccardo Chailly’s recording of Guglielmo Tell. At the time, Decca had one producer in the booth and an assistant producer in the studio with the performers, both with scores so that issues could be addressed expediently. This time, it was Pavarotti who was terrifying. He seemed indifferent to anyone else in the cast – and the cast of Guglielmo Tell was pretty much as all-star as could be assembled at the time. No ensemble, no chorus, no solo could ever offer enough ‘tenor presence’ in his opinion. Every ensemble, according to Pavarotti, was a tenor aria with everyone else an obbligato in the background. Mirella Freni, Sherrill Milnes and Nicolai Ghiaurov shook their heads in well-worn resignation. The producer James Mallinson suffered continuous abuse and threats. And yet Mallinson was the first colleague to tell me that Pavarotti was one of the most musical people any of us would ever work with. The more Pavarotti threatened and shouted, the more Mallinson did everything he could to accommodate him.

I continued to work with Pavarotti as studio producer on a number of other Decca recordings: La Gioconda and Mefistofele both recall an era when the studio could outmatch any opera house for sheer vocal casting. The attitudes towards Pavarotti from my senior colleagues Ray Minshull and Christopher Raeburn varied wildly. Minshull recognised that he was a gold mine, while Raeburn felt he was a bully. Yet while in the studio with Pavarotti, I had ample opportunities to speak with him and make up my own mind. His view was always in favour of fellow Italian singers; not because they were vocally better, but because he demanded the same clarity of characterisation in the language that he offered. He felt he was otherwise singing into a vacuum, like listening to one side of a telephone conversation. I saw his point of view, but at the time, international markets were such that casting a large opera for a studio recording required the biggest stars from the Met, Covent Garden, Vienna and Milan with occasional concessions to Paris and Berlin. Given the fact that rehearsals were simply establishing cues, pitches and beats, there were absolutely no discussions that determined dramatic characterisation or narrative purpose; the recording became for each big star whatever they brought to the party. Yet within this melee, Pavarotti always stood out with a declamatory vibrancy that brought the dramatic narrative to the music rather than the other way around.

Frankly, it was this particular genius of Pavarotti that irritated Solti the most during the Otello project. He had been Toscanini’s assistant and Toscanini considered Otello his personal property. Solti had only just been handed the fresh-off-the-press critical edition from Riccordi and he wasn’t going to allow Luciano to mess it up. Alan Blyth and other reviewers seemed to believe that virtually no material was taken from the first concert performance. They are mistaken. It was the only performance when Pavarotti managed to do things his way. Just listen to his Third Act ‘Dio! Mi potevi scagliar tutti i mali’ – Solti thrashed such rashness out of future performances, resulting in neither tenor nor conductor being able to exchange so much as a civil ‘good morning’ to one another.

That summer, Solti was conducting The Magic Flute in Salzburg and Pavarotti was relaxing in Pesaro. My summer was spent between the two locations. Pavarotti put us up in a small hotel near his villa but asked us to wake him first thing so we could start editing with his morning espresso. An editing console was set up in his bedroom for this purpose. He was always the perfect host, and in fact, the days in Pesaro were a delight. At home, he was unpretentious. I recall the plastic patio furniture purchased with collected motorway stamps from a petrol station. When the sun fell on them for any length of time, they became so soft that they became positively hazardous. It soon became a joke as to who would go flying as they unexpectedly settled down in a semi-melted plastic chair. Pavarotti had his family, friends, rehearsal pianist and mistress all in tow. A happy co-existence which daughters, wife and girlfriend accepted as the norm. There was no visible disharmony in this less-than-conventional set-up.

‘The musical differences between conductor and tenor meant that Solti was ready to murder Pavarotti’

Returning to Solti in Salzburg meant having to undo everything Pavarotti requested. He loathed the liberties Pavarotti took with the score and wondered rhetorically what possible value a new ‘critical edition’ of the work could offer if the tenor simply ignored what he was instructed. In addition, Pavarotti had gone beyond editing his own role. We spent painful hours trying to find takes of Kiri that he liked. It wasn’t that her Italian wasn’t crystalline in its perfection; it was simply too perfect and in many aspects, according to Pavarotti, meaningless as a result. This would occasionally result in choosing a take that was less musically literal. Solti again preferred the versions that were absolutely come scritto meaning a complete re-edit was sent back to Pavarotti, who in turn simply re-edited the opera back to his first preference. This went on until we had compromised on most points except the ‘Dio! Mi potevi scagliar tutti i mali’. Solti wanted what was in the new critical edition and Pavarotti was simply not budging. What he sang on the opening night was deeply moving and fundamentally powerful. The horse trading came to an end when someone on a higher pay grade informed Solti that Pavarotti sold more CDs. Solti’s final resigned comments on this now notorious passage was, ‘Oh well, at least it’s in the right octave’.

Listening to the recording again, I stand by my original comments: Kiri as Desdemona is the most beautiful voice available with a vulnerability that compensated for the immaculate perfection of Margaret Price’s representation. Nucci was an Italian with a grainy voice but utterly clear diction and, given the rapid-fire wordiness of the role, it would be hard to imagine making a compromise that went in favour of a more lustrous voice at the expense of the character. I parted company with Blyth’s quibbles on these points of casting. The orchestra was another matter. Recording a symphony orchestra rather than an opera orchestra in an opera performance offers its own challenges. The symphony orchestra has superb soloists who see every passage as an opportunity to shine and not as an adjunct within the dramatic fabric. Word-painting was simply less instinctive with an orchestra used to its centre-stage position rather than merely acting as musical underlay to a piece of theatre. The brass of the Chicago Symphony was like standing in front of a firing squad: your heart would beat faster as much in fear as anything else. It was not easy to control on the mixer. The final result, however, is perhaps more hair-raising than your average opera orchestra might have dared.

Other reviews were less kind, with most offering a sniffy variation along the lines of ‘He’ll never sing it on stage and the engineers have lifted him artificially’. It simply wasn’t true, and reading such commentary became increasingly frustrating. Pavarotti’s voice sailed across the loudest passages of the opera. By the final performances, the musical differences between conductor and tenor meant that Solti was ready to murder Pavarotti and so he let the orchestra off its leash. All to no avail: Pavarotti’s focus of tone was like a laser. No voice was so loved by so many microphones.

Finally, I’m asked if Pavarotti really couldn’t read music. The answer is no, he couldn’t. But then, so what? He was, as James Mallinson told me at the very beginning of my career at Decca, one of the most instinctively gifted musicians any of us would work with. It wasn’t easy, but looking back, it was miraculous.

This article originally appeared in the June 2019 issue of Gramophone. Make sure you never miss an issue, subscribe today.