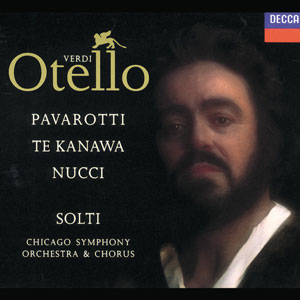

Verdi Otello

View record and artist detailsRecord and Artist Details

Composer or Director: Giuseppe Verdi

Genre:

Opera

Label: Decca

Magazine Review Date: 11/1991

Media Format: CD or Download

Media Runtime: 0

Mastering:

DDD

Catalogue Number: 433 669-2DH2

Tracks:

| Composition | Artist Credit |

|---|---|

| Otello |

Giuseppe Verdi, Composer

Alan Opie, Montano, Bass Anthony Rolfe Johnson, Cassio, Tenor Chicago Symphony Chorus Chicago Symphony Orchestra Dimitri Kavrakos, Lodovico, Bass Elzbieta Ardam, Emilia, Mezzo soprano Georg Solti, Conductor Giuseppe Verdi, Composer John Keyes, Roderigo, Tenor Kiri Te Kanawa, Desdemona, Soprano Leo Nucci, Iago, Baritone Luciano Pavarotti, Otello, Tenor New York Metropolitan Opera Children's Choir Richard Cohn, Herald, Bass |

Author: Alan Blyth

Forget all the hype, forget the larger-than-life figure of outdoor events, listen to the sincere and serious musician captured here as Otello. Nobody, I imagine, needs telling by now that Pavarotti was tackling the role for the first time, nor that he was out of sorts for the Chicago performances. By the time he and the caravanserai reached Carnegie Hall in New York the famous tenor was back in best voice and—as most of this recording derives from Carnegie Hall—we can hear just how noble and moving his assumption had become. In the publicity material accompanying this set, producer Michael Haas comments that, after years of non-Italians singing the role, we now once again have an Italian tackling it. Although he conveniently forgets Trieste-born Carlo Cossutta on Decca's earlier version under Solti (9/78—nla), his voice, like the Spaniards and Americans who have sung it, had a baritonal tinge. Haas quite rightly says ''It's time we had a tenor Otello''—and here he is.

Like the great Martinelli (Panizza/Music and Arts) before him, Pavarotti's voice hasn't the heft of the traditional tenor, but like his noble predecessor Pavarotti achieves the illusion of power through the focus of his tone, its incisive quality and, above all, by his precise attention to note and word values. Few Otellos since Martinelli have enunciated the text with such beauty and meaning. Whether in authority, joy or despair, this Otello is supremely articulate and moving. Listen in the opening scene to ''Abbasso le spade!'', in the love duet to ''A questa tua preghiera'', in the Third Act duet to phrase after phrase, in the final scene to ''E il ciel non ha piu fulmini'' (as Otello at last realizes Iago has duped him) and you hear Boito's memorable words delivered in authentic Italianate accents. Then there is the sense of line evident throughout combined with the consummate breath control—the opening phrase of the love duet taken in a single span—and the use of vibrato to enhance the emotion of the moment, as at ''Ma, o pianto'' in the Act 3 monologue and at the cries of ''Desdemona, Desdemona'' in the death scene. All this is the work of a serious artist who has scrupulously studied the score and followed what it tells him. Above all, his native emotions enable him to portray the Moor, set on the rack by Iago's wiles, with heartrending conviction.

Of course there isn't here the huge, clarion-like sound of a Zenatello (Bellezza/EMI—nla), Del Monaco (Karajan/Decca) or Vickers (Serafin/RCA), but that hardly matters when the heart of the matter is so achingly achieved, all in the service of a portrayal that is, in vocal terms, fully rounded. How amazing that this can be the work of a tenor in his mid-fifties. Faults? Just a single major one, chiefly found in the first two acts. Pavarotti, perhaps because he is unnecessarily anxious that his voice may not last the course, tends on occasion to hurry the music, sometimes giving the impression of getting ahead of the beat. That reduces the nobility and force of some key passages, most notably ''Ora e per sempre'', the farewell to arms. If you compare this performance with the measured declamation of Tamagno, the first Otello, at perhaps half the pace (various reissues), the music is almost unrecognizable. A happy mean is struck by the underrated Cossutta on Solti's earlier Decca version—though the voice sounds cloudy beside Pavarotti's clarity—by Vickers (very fine hereabouts) and by Domingo. In any case, by Act 3, Pavarotti begins to take his time, and the music responds.

I have mentioned the dread name of Domingo. It would perhaps be more than daring to make too many comparisons with Domingo's assumption (Levine/RCA and Maazel/EMI) except to say that both are deeply eloquent readings of the role, both valid in their own right, but the chance to hear once again a bright, open, Italianate timbre in the role proved especially rewarding.

In consequence of the fast speeds in Acts 1 and 2, Solti gets through them some six or seven minutes more quickly than say Karajan or Serafin—or indeed Solti himself in his earlier set. My point is further confirmed when his pacing of Acts 3 and 4 is only marginally quicker than in his previous version. As a whole, I found his direction, which marked his much-touted final appearances with his Chicago players, satisfying, but not offering any special insights. As in the other reading on disc, he is inclined to push the music along, not allowing it time to breathe, but the overall shape of each act is well conceived. As for the Chicago Symphony, in spite of its technical strengths, it cannot quite equal the Vienna Philharmonic as heard on the earlier Solti or on the Decca Karajan.

Dame Kiri made her unheralded debut at the Met as Desdemona 17 years ago. Returning to a role she has never recorded, she begins with little sense of involvement. Much of her contribution to the love duet is marred by inattention to consonants (more marked when heard alongside Pavarotti's exemplary enunciation) and, at climaxes, by some hardening in her lovely tone. She begins to find her form in voice and interpretation in her battle of words with Otello in Act 3. She sings the Willow Song and Ave Maria with care over weighting of tone and phrase. But in vocal terms she is surpassed by Tebaldi (Karajan), Margaret Price (when a damehood for her?) on the earlier Solti and in terms of moving interpretation, by virtue of Italianate diction and interior feeling, by Scotto on Levine (RCA) and by Ricciarelli (Maazel).

Nucci is a disappointing Iago. Manuela Hoelterhoff, the witty critic of the Wall Street Journal, wrote after the Carnegie Hall performance of his ''first at-least-one-size-too-small Iago''. Perhaps in compensation he over-accents practically every word and aspirates in an ungainly way. This may be effective in a rather obvious, playing-to-the-gallery way, but it quite misses the subtleties of great Iagos of the past, such as Gobbi (Serafin), Bacquier (Solti 1), even more Tibbett (Music and Arts) have found in the part. Listen to ''Era la notte'' in these performances as evidence.

Two British singers make an impression in lesser roles. Anthony Rolfe Johnson is a pleasingly lyrical Cassio, Alan Opie a resonant Montano. Dimitri Kavrakos makes more than most basses of Lodovico's brief announcements.

I very much admire the recording as such, which sounds a truthful, unexaggerated reproduction of what was heard in the concert-hall with only one or two distant coughs to worry the most sensitive. Likewise in a live context, we are spared all those stage 'effects' so beloved of producers in a studio. In sum this set houses a great Otello rather than great Otello for which you might turn to Panizza (a blazing night at the Met in tolerable sound, see 9/91) or Serafin, but remember Toscanini's legendary performance is expected any day from RCA.'

Like the great Martinelli (Panizza/Music and Arts) before him, Pavarotti's voice hasn't the heft of the traditional tenor, but like his noble predecessor Pavarotti achieves the illusion of power through the focus of his tone, its incisive quality and, above all, by his precise attention to note and word values. Few Otellos since Martinelli have enunciated the text with such beauty and meaning. Whether in authority, joy or despair, this Otello is supremely articulate and moving. Listen in the opening scene to ''Abbasso le spade!'', in the love duet to ''A questa tua preghiera'', in the Third Act duet to phrase after phrase, in the final scene to ''E il ciel non ha piu fulmini'' (as Otello at last realizes Iago has duped him) and you hear Boito's memorable words delivered in authentic Italianate accents. Then there is the sense of line evident throughout combined with the consummate breath control—the opening phrase of the love duet taken in a single span—and the use of vibrato to enhance the emotion of the moment, as at ''Ma, o pianto'' in the Act 3 monologue and at the cries of ''Desdemona, Desdemona'' in the death scene. All this is the work of a serious artist who has scrupulously studied the score and followed what it tells him. Above all, his native emotions enable him to portray the Moor, set on the rack by Iago's wiles, with heartrending conviction.

Of course there isn't here the huge, clarion-like sound of a Zenatello (Bellezza/EMI—nla), Del Monaco (Karajan/Decca) or Vickers (Serafin/RCA), but that hardly matters when the heart of the matter is so achingly achieved, all in the service of a portrayal that is, in vocal terms, fully rounded. How amazing that this can be the work of a tenor in his mid-fifties. Faults? Just a single major one, chiefly found in the first two acts. Pavarotti, perhaps because he is unnecessarily anxious that his voice may not last the course, tends on occasion to hurry the music, sometimes giving the impression of getting ahead of the beat. That reduces the nobility and force of some key passages, most notably ''Ora e per sempre'', the farewell to arms. If you compare this performance with the measured declamation of Tamagno, the first Otello, at perhaps half the pace (various reissues), the music is almost unrecognizable. A happy mean is struck by the underrated Cossutta on Solti's earlier Decca version—though the voice sounds cloudy beside Pavarotti's clarity—by Vickers (very fine hereabouts) and by Domingo. In any case, by Act 3, Pavarotti begins to take his time, and the music responds.

I have mentioned the dread name of Domingo. It would perhaps be more than daring to make too many comparisons with Domingo's assumption (Levine/RCA and Maazel/EMI) except to say that both are deeply eloquent readings of the role, both valid in their own right, but the chance to hear once again a bright, open, Italianate timbre in the role proved especially rewarding.

In consequence of the fast speeds in Acts 1 and 2, Solti gets through them some six or seven minutes more quickly than say Karajan or Serafin—or indeed Solti himself in his earlier set. My point is further confirmed when his pacing of Acts 3 and 4 is only marginally quicker than in his previous version. As a whole, I found his direction, which marked his much-touted final appearances with his Chicago players, satisfying, but not offering any special insights. As in the other reading on disc, he is inclined to push the music along, not allowing it time to breathe, but the overall shape of each act is well conceived. As for the Chicago Symphony, in spite of its technical strengths, it cannot quite equal the Vienna Philharmonic as heard on the earlier Solti or on the Decca Karajan.

Dame Kiri made her unheralded debut at the Met as Desdemona 17 years ago. Returning to a role she has never recorded, she begins with little sense of involvement. Much of her contribution to the love duet is marred by inattention to consonants (more marked when heard alongside Pavarotti's exemplary enunciation) and, at climaxes, by some hardening in her lovely tone. She begins to find her form in voice and interpretation in her battle of words with Otello in Act 3. She sings the Willow Song and Ave Maria with care over weighting of tone and phrase. But in vocal terms she is surpassed by Tebaldi (Karajan), Margaret Price (when a damehood for her?) on the earlier Solti and in terms of moving interpretation, by virtue of Italianate diction and interior feeling, by Scotto on Levine (RCA) and by Ricciarelli (Maazel).

Nucci is a disappointing Iago. Manuela Hoelterhoff, the witty critic of the Wall Street Journal, wrote after the Carnegie Hall performance of his ''first at-least-one-size-too-small Iago''. Perhaps in compensation he over-accents practically every word and aspirates in an ungainly way. This may be effective in a rather obvious, playing-to-the-gallery way, but it quite misses the subtleties of great Iagos of the past, such as Gobbi (Serafin), Bacquier (Solti 1), even more Tibbett (Music and Arts) have found in the part. Listen to ''Era la notte'' in these performances as evidence.

Two British singers make an impression in lesser roles. Anthony Rolfe Johnson is a pleasingly lyrical Cassio, Alan Opie a resonant Montano. Dimitri Kavrakos makes more than most basses of Lodovico's brief announcements.

I very much admire the recording as such, which sounds a truthful, unexaggerated reproduction of what was heard in the concert-hall with only one or two distant coughs to worry the most sensitive. Likewise in a live context, we are spared all those stage 'effects' so beloved of producers in a studio. In sum this set houses a great Otello rather than great Otello for which you might turn to Panizza (a blazing night at the Met in tolerable sound, see 9/91) or Serafin, but remember Toscanini's legendary performance is expected any day from RCA.'

Discover the world's largest classical music catalogue with Presto Music.

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £8.75 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Full Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Full website access

From £11.00 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.