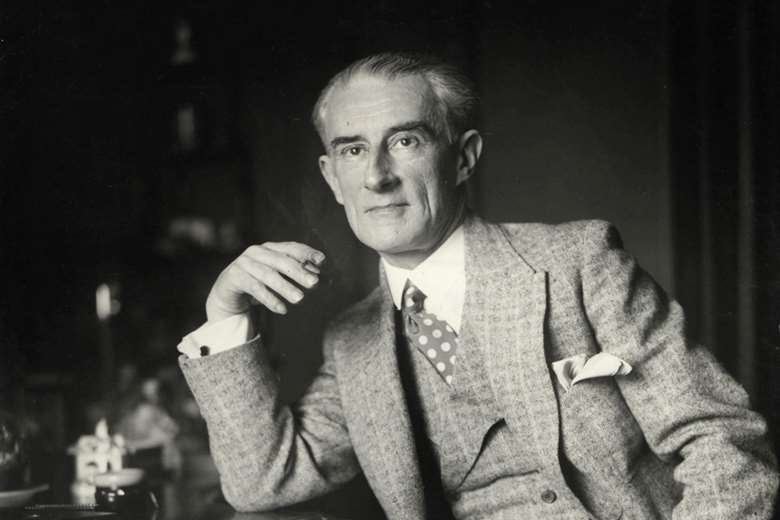

Unravelling Maurice Ravel: a portrait of the composer at 150

Mark Pullinger

Thursday, February 13, 2025

To mark the 150th anniversary of Maurice Ravel’s birth, Mark Pullinger conjures a portrait of this multifaceted composer through his exquisitely crafted works

Vaughan Williams, who briefly studied with Ravel in 1907-08, recalled that the French composer’s motto was ‘complexe mais pas compliqué’, a description that could equally apply to a man who was something of an enigma.

In terms of output, Ravel composed a relatively modest catalogue of works, but each was exquisitely crafted. Listening to the Piano Concerto in G, you get an aural picture of him: stylish, sophisticated, a dapper dresser. Alma Mahler, with whom Ravel once stayed when he gave concerts in Vienna, called him a narcissist. He could carry a certain bourgeois air. Fellow Paris Conservatoire student the pianist Alfred Cortot recalled him as ‘a deliberately sarcastic, argumentative and aloof young man, who used to read Mallarmé and visit Erik Satie’.

His repeated failure to win the conservatoire’s coveted Prix de Rome caused something of a scandal (known as ‘L’affaire Ravel’) in 1905, and his distrust of – or disdain for – the Establishment is a possible reason he declined the Légion d’honneur in 1920. Ravel certainly had a caustic wit and occasionally a short fuse too. Paul Wittgenstein, who commissioned the Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, was prone to making changes to the score, justifying them by claiming, ‘Performers must not be slaves.’ Ravel responded, ‘Performers are slaves!’

Listening to the Piano Concerto in G, you get an aural picture of Ravel: stylish, sophisticated, a dapper dresser

In concert and on disc, Ravel is often paired with Debussy. The relationship between the two men was complex, although both intensely disliked the term ‘Impressionist’ to describe their music. Ravel was bowled over by the premiere of Pelléas et Mélisande and allegedly attended all 14 performances of its initial run at the Opéra-Comique. Debussy admired the young Ravel, and in 1904 he went to the run-through of the latter’s String Quartet, which owes a debt to the older composer. But thereafter, relations between the men cooled. When, in 1905, the Érard company commissioned Ravel’s Introduction and Allegro to showcase its new double-action pedal harp, it was perhaps trying to capitalise on the growing rift between him and Debussy, who had recently composed his Danse sacrée and Danse profane for Pleyel’s chromatic harp.

A cigarette was almost permanently wedged between Ravel’s fingers. In his outstanding biography, Roger Nichols quotes Paul Valéry, who used to say, ‘Ravel’s continual need for tobacco served to increase the smokescreen between him and the fools of this world.’

Ricardo Viñes, his fellow student and close friend, described Ravel as secretive, ‘a man at odds with his surroundings’. He kept his private life private, once confessing, ‘The only love affair I have ever had was with music.’ And I propose that it’s through his music – via four connections or routes – that we get to know the different aspects of the real Ravel.

Ravel the Swiss clockmaker

When Stravinsky described Ravel as ‘the most perfect of Swiss clockmakers’ he probably meant nothing derogatory, being a meticulous composer himself; but he can hardly have realised just how close to the mark he came. One of Ravel’s great-great-grandfathers, Denis Gabriel Rousset, was described on his marriage certificate as a maître horloger (master clockmaker), so the composer was literally a descendant of a Swiss clockmaker. Ravel’s father, Pierre-Joseph, was a Swiss inventor and civil engineer who in 1868 patented a steam generator heated by mineral oils and who subsequently invented the supercharged two-stroke engine. After the Franco-Prussian War, Pierre-Joseph went to Spain as an engineer on Gustave Eiffel’s railways, and in Aranjuez in 1872 he met Marie Delouart, descended from Basque gypsies, who would soon become his wife.

Centre: the house where Ravel was born and lived for a short while as an infant, in the port of the French-Basque town of Ciboure (photography: Hemis, Alamy Stock Photo)

Stravinsky’s quip was probably referring to the precision of Ravel’s writing. When I wrote a cover story for the centenary of Debussy’s death (3/18), the differences between him and Ravel arose. Composer Robin Holloway described Ravel to me as ‘a fantastic machine which cannot go wrong if you obey the instructions … All conductors would say the same: Ravel you obey, Debussy you have to interpret.’ Ravel’s scores are so intricate, so detailed, that performing them should go like … clockwork.

Clocks and bells themselves chime through much of his music. In his earliest song, Ballade de la reine morte d’aimer (1893), the little bells of Thule toll away in the piano part as the story is told of the king’s sister, who dies of love. A bell tolls ‘unwearyingly’ (Ravel’s description to pianist Henriette Faure) in ‘Le gibet’, the central panel of Gaspard de la nuit where a corpse hangs on a gibbet in a desert.

Miroirs, another piano suite, closes with ‘La vallée des cloches’, inspired by the sounds of Paris. The bell sounding in rolled chords at the end evokes (again according to Faure) ‘Le Savoyarde’, a 19-tonne monster, the largest bell in France, which had been installed in the Basilique du Sacré-Coeur in Montmartre in 1895. It’s remarkable to think that Ravel’s tintinnabular picture precedes Debussy’s masterpiece La cathédrale engloutie by five years.

Clocks are central to Ravel’s L’heure espagnole, an operatic farce about 18th-century Toledo clockmaker Torquemada, who every Thursday leaves his workshop to tend to the town’s municipal clocks. During his absence his wife, Concepción, entertains two lovers, poet Gonzalve and rich banker Don Iñigo Gomez, but her rendezvouses are foiled when muscly muleteer Ramiro calls to have his watch repaired. Cue her two amours hiding in clocks and being carted up to her bedroom and back by the unwitting Ramiro. Ravel had tremendous problems getting it staged by the Opéra-Comique. Thanks to the prudish director Albert Carré, its premiere was delayed by a few years.

With typical precision, Ravel demands the ticking of three clocks together from the first down-beat of the introduction to L’heure espagnole, proceeding at 40, 100 and 232 beats per minute respectively, so that they coincide at every 18th crotchet. ‘What a miraculous masterpiece,’ wrote Poulenc later, while he was composing Les mamelles de Tirésias. ‘But what a dangerous example … When you don’t have Ravel’s magical precision, which alas is the case for me, you have to set your music on sturdy feet.’

Around the same time as he was working on L’heure espagnole, Ravel was tinkering with another opera, La cloche engloutie, based on Gerhart Hauptmann’s 1896 play, but nothing came of it and the project sank without trace.

Ravel in the nursery

L’enfant et les sortilèges, Ravel’s second opera, takes us from Spain back into the nursery. A world of childhood is evoked in this fantastical work, composed to a libretto by Colette, in which a naughty child is confronted by objects in his room: a teapot and a Chinese teacup dancing a foxtrot, anyone? He is then transported to the garden, which is populated by singing animals and trees that have been tortured by the Child; in revenge, they attack him, but in the ensuing mêlée a squirrel is injured. The Child bandages its paw and the animals, seeing this kinder side to his nature, help him back home to his mother. The Child’s falling fourth cadence as he calls ‘Maman’ at the end can reduce stronger souls than I to tears. It surely struck a resonant chord with Ravel himself, whose own maman, Marie, died in January 1917, shortly before he began work on the opera. Ravel was very close to his mother – both he and his younger brother, Édouard, were still living at home when she passed away.

L’heure espagnole, Glyndebourne, 2012 (photography: Simon Annand, Glyndebourne Productions Ltd)

Marie Delouart was born in Ciboure and descended from the Cascarots, a racial minority of Basque gypsy origin established in the coastal area, especially in Saint-Jean-de-Luz. There was a societal gulf between her and Ravel’s father: he was educated and an engineer; she was illegitimate and practically illiterate. The change of life for her on moving to Paris must have been enormous. Ravel himself was also born in Ciboure, shortly after Marie returned there to attend to her dying mother in 1875.

Ravel and his mother were devoted to each other. Little Maurice had long hair until his teens; a friend described the young boy as resembling ‘a Florentine page’. Marie sang Basque and Spanish lullabies to him when he was an infant, and her influence found its way into several scores, from the Rapsodie espagnole through to his final work, the song-cycle Don Quichotte à Dulcinée. The Cascarots of Ciboure were credited with introducing the fandango, the dance that Ravel initially intended to use in creating a ballet for Ida Rubinstein, but it was the infamous Boléro that ultimately resulted from this commission.

Ravel never really left childhood behind. Ibert’s widow recalled a time when the adult Ravel’s absence from a party was noticed and he was eventually found in the nursery, playing with the children’s toys. He loved fairy stories and spending time with children. It was for the children of Cipa and Ida Godebski, Mimie and Jean, that he composed his four-hand piano duet Ma Mère l’Oye, a suite of pieces depicting stories such as ‘Sleeping Beauty’, ‘Tom Thumb’ and ‘Beauty and the Beast’. Decades later, Mimie recalled, ‘Ravel was my favourite because he used to tell me marvellous stories. I would sit on his knee and indefatigably he would begin “Once upon a time …”’

Ravel orchestrated Ma Mère l’Oye in 1911, then expanded it to accompany a ballet, almost doubling the length of the suite. The delicate gossamer textures of Ma Mère l’Oye are enchanting, Ravel truly seeing the world through the eyes of children. In ‘Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes’ one can hear the influence of the Javanese gamelan, which the composer first heard at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris.

Ravel and the Russians

It was during the same Exposition Universelle that the 14-year-old Ravel regularly made the two-mile walk to the Trocadéro, where he saw Rimsky-Korsakov conduct concerts of Russian repertoire by Glinka, Tchaikovsky and the Mighty Handful. They included Rimsky-Korsakov’s own Antar, which must have made an impact because eight years later Ravel and Ricardo Viñes played it as a piano duet.

In 1910, Ravel even made use of Rimsky-Korsakov’s score when commissioned to provide incidental music for Lebanese writer Chekri Ganem’s new play based on the Arabic epic The Romance of Antar. He did some cutting and pasting, inserted part of the ‘vision of Cleopatra’ scene from Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera-ballet Mlada and added his own interludes (Leonard Slatkin’s premiere recording with the Orchestre National de Lyon is worth a listen).

Ravel clearly had a fascination with Rimsky-Korsakov and orientalism. Sheherazade (1888) made such an impression that his first (surviving) orchestral work was an 1898 ouverture de féerie that was intended as the prelude to an Arabian Nights opera. Critic Henry Gauthier-Villars accused Ravel of ‘clumsy plagiarism’ and the operatic project went nowhere. The composer himself later admitted it was ‘a clumsy botch-up and full of whole-tone scales; so many indeed that I was put off them for life’.

But Ravel did return eastwards with another Shéhérazade (1903), three songs to heady texts by Tristan Klingsor (the Wagnerian pseudonym adopted by Léon Leclère) which imaginatively evoke the perfumed atmosphere of The Arabian Nights. ‘It’s full of things that I am ashamed today to have written,’ Ravel later told his pupil Manuel Rosenthal. ‘But there is something in this composition that I have never found again.’

It wasn’t just Rimsky-Korsakov that fascinated Ravel though. He proposed that the secret signal for the private meetings of Les Apaches – a group of young Parisian artists who met to share ideas – should be the opening motif of Borodin’s Second Symphony. And in ‘Scarbo’, the final part of Gaspard de la nuit, Ravel was aiming to outdo Balakirev’s finger-crunching Islamey. ‘I wanted to write an orchestral transcription for the piano!’

Ravel hugely admired Mussorgsky’s music. As a critic, he reviewed Feodor Chaliapin in Boris Godunov (he was not impressed by his ‘sinister cacklings and cavernous groans’), and he was decades ahead of his time in calling for a return to Mussorgsky’s original orchestration.

Ravel’s association with Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes led to a mutually supportive friendship with Stravinsky. Ravel was one of the few who understood Le sacre du printemps at its premiere. Stravinsky later wrote: ‘In the chaos of conflicting opinions, my friend Maurice Ravel was almost the only one to put his finger on the nub. He … said that the novelty of the Sacre lay not in the detail, the orchestration or the technique of construction, but in the musical essence.’ Invited by Diaghilev, Ravel collaborated with Stravinsky on an orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina.

Ravel’s greatest feat of orchestration, though, was the vibrant palette he applied to Pictures at an Exhibition, a lucrative commission (10,000 francs) from Serge Koussevitzky. Ravel was so concerned about being faithful to Mussorgsky that he asked Michel-Dimitri Calvocoressi to source him a copy of the original piano score, but, ironically, he was sent Rimsky-Korsakov’s faulty edition instead (Mussorgsky’s original was not published until 1931).

Ravel on the dance floor

The finest work to emerge from Ravel’s collaboration with Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes was also his longest: the ballet Daphnis et Chloé. Diaghilev’s commission came in May 1909 but it had a protracted birth and wasn’t premiered until June 1912 at the Théâtre du Châtelet, with sets designed by Léon Bakst and choreography by Michel Fokine.

It wasn’t always a happy collaboration. Fokine, who was effectively serving out notice after a spat with Diaghilev, was delivering his third ballet on an ancient Greek theme after Narcisse (which ended up using sets originally intended for Daphnis) and the sultry L’après-midi d’un faune, starring Vaslav Nijinsky. Fokine felt that Ravel’s score lacked virility. ‘Fokine doesn’t know a word of French and all I know of Russian is how to swear in it,’ Ravel wryly commented.

L’après-midi d’un faune had been allotted an excessive 120 rehearsals by Diaghilev and was premiered just 10 days before Daphnis, rather stealing the thunder from the longer work. Tamara Karsavina and Nijinsky danced the title-roles in Daphnis, and Pierre Monteux conducted the Orchestre Colonne. The score is terrific (Ravel described it as a symphonie chorégraphique) – full of lush harmonies, imaginative use of a wordless offstage chorus and one of the most evocative sunrises ever written. The closing ‘Danse générale’ is surely indebted to the finale of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazade. Critic Pierre Lalo wrote a scathing review: ‘It is lacking the first quality of ballet music: rhythm’; but Jean Cocteau was bowled over: ‘Daphnis is … one of those works that land in our hearts like a meteorite, from a planet whose laws will remain forever mysterious.’

From the early piano piece Menuet antique (1895), his first published work, to the Valses nobles et sentimentales, dance was a recurring feature of Ravel’s output. One of the most popular of these works was the Pavane pour une infante défunte (whose title was chosen for its euphonious qualities). Listening to a piano roll of the composer playing it (just 5'08") reinforces Ravel’s irritation at other pianists playing it too slowly. He once gently ticked off the young pianist Charles Oulmont: ‘I wrote a Pavane for a dead princess and not a dead Pavane for a princess.’

Ravel poured new wine into old bottles with Le tombeau de Couperin – a piano suite that pays homage to French Baroque dance. Ravel began it in 1914 (Forlane) but it wasn’t completed until 1917, each movement poignantly dedicated to friends who had died in the Great War.

‘I’ve written only one masterpiece,’ Ravel drily told Honegger. ‘Boléro. Unfortunately, there’s no music in it.’ But for me, Ravel’s real dance masterpiece is La valse. It had a long gestation period, possibly as far back as 1905 when Viñes and Ravel attended the Paris Opéra ball. In his diary, Viñes wrote, ‘I thought of death, of the ephemeral nature of everything, I imagined balls from past generations, who are now nothing but dust … What horror. Oblivion!’ Did Viñes share these thoughts with Ravel? The following year, Ravel considered a piece with the working title ‘Wien’. It wasn’t until 1919-20 that he composed it, proposing a ballet. At the two-piano playthrough, however, Diaghilev was unimpressed: ‘It’s a masterpiece … but it’s not a ballet … it’s the portrait of a ballet.’ Ravel calmly gathered his things and left the room without saying a word.

Ravel described La valse as ‘a sort of apotheosis of the Viennese waltz’, and his preface to the score sets the action in an imperial court around 1855. He vigorously denied that it was anything to do with post-war Europe. Neither did he ‘envision a dance of death or a struggle between life and death’ – although that’s a difficult association to dislodge once you’ve seen George Balanchine’s version, created for New York City Ballet in 1951, which precedes it with the Valses nobles et sentimentales, a maelstrom in which the figure of Death memorably claims his victim. Not for nothing did Erich Kleiber describe La valse as ‘poisoned with absinthe’.