Mieczysław Weinberg: a complete guide to the composer's life and music

Thursday, January 23, 2020

To mark Mieczysław Weinberg’s centenary, David Fanning explores the ever-growing catalogue of the Russian composer’s extraordinary and underappreciated music

Welcome to Gramophone ...

We have been writing about classical music for our dedicated and knowledgeable readers since 1923 and we would love you to join them.

Subscribing to Gramophone is easy, you can choose how you want to enjoy each new issue (our beautifully produced printed magazine or the digital edition, or both) and also whether you would like access to our complete digital archive (stretching back to our very first issue in April 1923) and unparalleled Reviews Database, covering 50,000 albums and written by leading experts in their field.

To find the perfect subscription for you, simply visit: gramophone.co.uk/subscribe

Twenty-five years ago, bedridden, with only 14 months to live, Weinberg celebrated his 75th birthday. The Russian musical world, however, did not. Concert life in post-Soviet Russia was in poor shape – one wry observer commented that ‘the concert halls were empty and porn cinemas full’. Even before the death of Shostakovich in 1975, concert-goers’ tastes had been changing, as audiences gradually became aware of the ‘underground’ music of a younger generation (Schnittke, Denisov, Sofia Gubaidulina and others), leaving the darkly unflamboyant, resolutely humanist utterances of late-period Shostakovich and his closest musical friend with an aura of déjà entendu.

Mieczysław Weinberg (1919-96) lived just long enough to witness the beginnings of a new wave of interest. A series of CDs on Olympia began to be released in the 1990s, and his friend Tommy Persson (the Swedish judge who had brought medicines from the West which almost certainly gave the composer a few extra years of life) was able to present Weinberg with the third and fourth of those issues, containing suites from the ballet The Golden Key and the Piano Quintet and Twelfth String Quartet. The first of the series – a 1994 reissue of Symphonies No 6 and 10 recorded in the 1970s – contained an essay by Persson’s friend the broadcaster and documentary maker Per Skans, who was collecting materials towards a life-and-works study up to his death in 2007. Skans went straight to the point, describing Weinberg’s neglect as ‘scandalous’. How amazed he and the composer would have been at the plethora of recordings now available in this centenary year; and how bittersweetly gratifying for Persson to realise that his unsung initiative in underwriting several of the 17 Olympia Weinberg CDs that appeared between 1994 and 2000 not only kept the music alive for specialist collectors but touched off what has been described in Russia as the ‘Weinberg boom’. Since 2006 there have been five international conferences, books in Russian, Polish, English and German, and countless performances, not least a belated triple debut at this year’s BBC Proms (the Cello Concerto, the Third Symphony and String Quartet No 7).

Join the lobby for Melodiya to make transfers of LPs of the Sixth Piano Sonata by Yablonskaya and/or Mdivani

Not that Weinberg had been obscure in his lifetime. His dramatic life story was no secret. He had grown up in Warsaw, had two narrow escapes from German invasions, and finally settled in Moscow from September 1943. There he gained in Shostakovich a close musical friend and indefatigable supporter. The first five Moscow years were conspicuously successful. Then the ‘anti-formalism’ and ‘anti-cosmopolitan’ campaigns beginning in 1948 put the brakes on, and after five years of being tailed by the secret police Weinberg was briefly incarcerated in the Lubyanka and Butyrka prisons. Following a steady recovery, in the 1960s (his ‘starry years’, as he described them) he was championed by the likes of Kondrashin, Rudolf Barshai, Mstislav Rostropovich, Emil Gilels, Leonid Kogan, the Borodin Quartet and Kurt Sanderling, and later on by Vladimir Fedoseyev. Even so, his Polish-Jewish background and his reluctance to assume official positions or to take on teaching meant that his music was never top-priority export material. Avid collectors in the West could have found his Fourth Symphony, Violin Concerto and Trumpet Concerto on EMI LPs under the licence agreement with Melodiya in the 1970s, and dribs and drabs had come through earlier than that on the Westminster and Monitor labels. Mail order outlets and (for British enthusiasts like myself) Collet’s bookshop in London’s Charing Cross Road brought occasional Melodiya treats, stimulating but hardly satisfying the appetite.

This may be the place to say that Melodiya’s recent survey of selected Weinberg chamber recordings from the Soviet era is both eminently collectable and something of a missed opportunity. Although there are treasures (Alexander Brusilovsky in the Second Solo Violin Sonata; Fyodor Druzhinin in the First Solo Viola Sonata; Weinberg accompanying his two cello sonatas; Timofey Dokshitser in the Trumpet Concerto), the three discs could comfortably have been accommodated on two; alternatively, the extra space could have been given over to Weinberg’s own superb account of his Piano Quintet with the Borodin Quartet and, say, Gilels’s superb reading of the Fourth Piano Sonata.

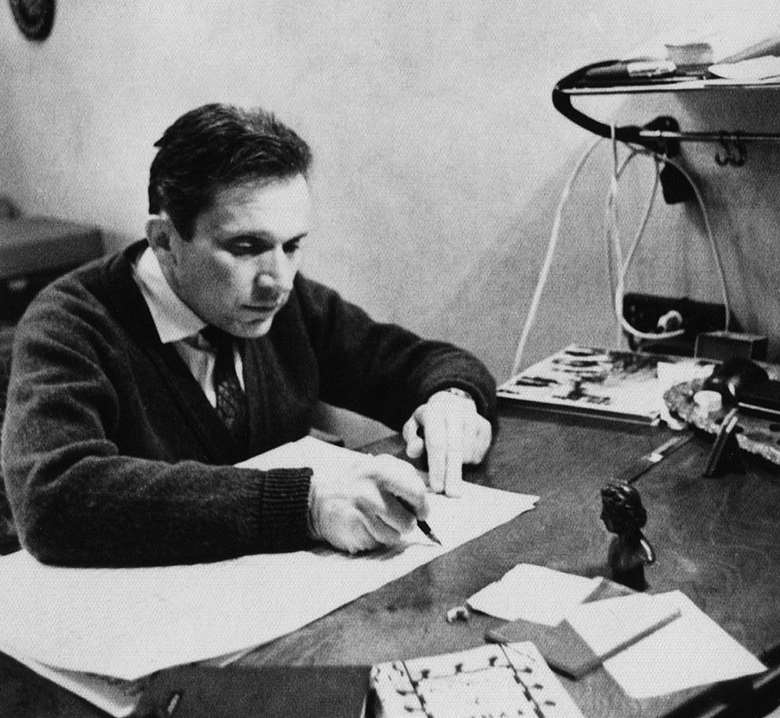

Weinberg accompanies Oistrakh, Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich in the premiere of Shostakovich’s Op 127 in Moscow, 1967 (photography: courtesy of Olga Rakhalskaya)

For all the sterling work of the Olympia pioneers (Murray McLachlan in the six piano sonatas, Yosif Feigelson in the solo cello works, the young Dominant and Gothenburg quartets in some of the string quartets, Thord Svedlund conducting the Second Symphony and three of the chamber symphonies), it was a second wave of champions that put Weinberg indelibly on the map. The Danel Quartet began their Weinberg journey in the same year that Olympia kicked off its recorded series, leading to six CPO CDs (released as a set in 2014) of the complete 17 quartets (1937-86). David Pountney took the bold decision to mount Weinberg’s first opera, the Auschwitz-based The Passenger (1967-68), in its first ever staged production, in Bregenz in July 2010. Gidon Kremer put his own services and those of his hand-picked Kremerata Baltica behind an ongoing series of performances and recordings. Other doughty advocates feature in the course of this survey.

The Trumpet Concerto is in many ways the most distinctive of his concertos, and Håkan Hardenberger is about to take it on

Virtually all the genres Weinberg worked in have now been covered (see Claude Torres’s comprehensive and regularly updated online discography at musiques-regenerees.fr/Vainberg/WeinbergDiscographie.html). Even the 70 or so films for which he provided scores are almost all traceable online; the Palme d’Or-winning The Cranes Are Flying (1957) is on DVD, and subtitled versions of the three Soviet Winnie-the-Pooh (Vinni-Pukh) cartoons he scored – their charming music as familiar to Russians as that of any Walt Disney cartoon to Westerners – can be found at a few keystrokes. I shall come on to the remaining gaps in my conclusion. The only other necessary preliminary is a declaration of interest, since a number of the CDs I shall mention contain my own booklet essays or reflect some level of consultation with me. I won’t let that sway my judgement, though I cannot promise to have heard every single available version of the more frequently recorded works.

Chamber Music

There are good reasons for beginning a survey with the chamber music. It was in the string quartet that the young Weinberg first made his mark. He composed six by the age of 26, with no duds (as the Danel Quartet’s complete cycles this year in Manchester, Washington DC, Hamburg and Amsterdam have amply proved). It is here that his personal voice is revealed in its most developed form: its blend of stoical lyricism, defiance, painful intimacy, subtle shades of Jewish klezmer idiom and a willingness to experiment (to a Bartókian level, at least). And it’s here that the relationship with Shostakovich is most apparent, with a mutual influence flowing between Weinberg and his great mentor and friend. The Danel’s six discs for CPO are an obvious recommendation, for the excitement of their pioneering zeal as much as for their top-notch performance values, though the Silesian Quartet’s cycle on Accord, comprising Quartets Nos 7 to 13 at the time of writing, offers a scarcely less distinguished alternative. In his last decade, Weinberg revised and recast the Second, Third and Fifth Quartets as his first three chamber symphonies, the first two of which won him his only USSR State Prize (1990). It seems that no one realised their origins, but instead they were taken for bona fide late masterpieces, which must have been a source of some wry amusement for him. The Kremerata Baltica recordings of all four chamber symphonies are an obvious choice (coupled with an arrangement of the Piano Quintet for piano, strings orchestra and percussion), though personally I could have done without the arrangement, convincing though it is, because that would have allowed room for the first movement repeat in the Second Chamber Symphony, which is, after all, one of Weinberg’s most neoclassical works. Of the various rival versions, I warm especially to the recent issue on Naxos of Nos 1 and 3 from the East-West Chamber Orchestra (reviewed next issue).

Given its memorable ideas, confident working out and quota of surprises (including a rumbustious Irish-sounding gigue in the last movement), it is natural that the Piano Quintet should be one of Weinberg’s most frequently recorded works. I’ve heard most of the 11 recordings to date, and while none is less than respectable, it would be absurd not to nominate first and foremost the composer’s own with the Borodin Quartet. He was shaping up for a career as concert pianist before the Nazi invasion of Poland, and only tuberculosis of the spine contracted in wartime compelled a shift in focus to composition. Thereafter, he still played to a high professional standard: hear him in the famous duet recording of Shostakovich’s 10th Symphony with the composer, or the premiere of the latter’s Blok Romances, Op 127, with Galina Vishnevskaya, David Oistrakh and Rostropovich, when he stood in for the indisposed Sviatoslav Richter. Apart from the sheer vitality of the Quintet performance, it’s a valuable document of the kinds of liberty he took with his own text. So, too, is his accompaniment of Alla Vasilieva in his two Cello Sonatas (on the above-mentioned Melodiya chamber music set).

Of Weinberg’s 29 sonatas, the six for violin and piano have been particularly favoured – unsurprisingly, given their winning blend of substance and idiomatic writing. Of the three excellent sets that include all six, I favour Linus Roth and José Gallardo (Challenge Classics, 9/13). Kremer can be heard on a recent Deutsche Grammophon CD in the uncompromising Sixth Sonata, along with a terrific account of the Piano Trio, which has been as frequently recorded as the Quintet and is comparable in its passion, dramatic immediacy and command of large-scale structure. To hear Kremer with Martha Argerich in the Fifth Sonata (my personal favourite), you’ll need Warner Classics’ three-disc set of her live recordings from the 2014 Lugano Festival.

For sundry other chamber works, including the only current version of the Bassoon Sonata (on CPO, valuably coupled with other rarities and the top-notch Clarinet Sonata), pianist Elisaveta Blumina has been a prime mover (mainly for CPO, but also for Naxos). She herself has been working her way impressively through the solo piano sonatas. For comprehensive coverage of the piano works we have to thank Allison Brewster Franzetti; she alone has tackled the fiendishly difficult Partita, Op 54, for instance (on a four-disc set from Grand Piano). For the very finest in piano recordings, do seek out Gilels in the Fourth Sonata, and join the lobby for Melodiya to make transfers of LPs of the Sixth Piano Sonata (my personal favourite) by Oxana Yablonskaya and/or Marina Mdivani.

The one area in which Weinberg composed but Shostakovich did not is the solo string sonata; there are three for violin, four for viola, four for cello and a single one for double bass. They range from the wistfully lyrical First Sonata for cello, to the finger-torturing First Sonata for violin, to the remarkably sustained, almost symphonic Sonata for double bass. For the violin sonatas, Roth is again the obvious recommendation, conveniently available on a Challenge Classics disc (9/16); but for the viola sonatas I’m torn between excellent versions by Julia Rebekka Adler (Neos, 6/10) and Viacheslav Dinerchtein (Solo Musica), and for the cello sonatas between Yosif Feigelson (reissued on Naxos, 11/97) and more recently Marina Tarasova (Northern Flowers). Much as I like Tarasova’s heart-on-sleeve passion, Feigelson’s two volumes also come with the highly experimental 24 Preludes and the alternative first movement of the Fourth Cello Sonata (for the revised version of the Second we can turn to Emil Rovner on Divox). Kremer’s resourceful solo violin arrangements of the 24 Preludes can be heard not only on CD (Accentus, 6/19) but also on DVD (also Accentus) complemented by moody photographic images.

Orchestral music

Weinberg’s 22 symphonies (in addition to the four chamber symphonies) run through his entire career, from No 1 in 1942-43, dedicated to the Red Army (which he regarded as having saved him from the Nazis), to No 22, left unorchestrated at his death in 1996. The only significant chronological gap is between his Third of 1949 (the one much lauded at this year’s Proms) and the Fourth of 1957 – the years of his tailing by the NKVD, persecution, imprisonment and recovery. The symphonies comprise three layers: straightforward non-programmatic instrumental works, symphonies with programmes and/or vocal or choral elements, and symphonies for strings.

Chandos and Naxos have been parcelling out the symphonies between them, with some additional sterling pioneer efforts from Toccata Classics (the plangent 21st, Kaddish, which is dedicated to the victims of the Warsaw ghetto – A/14; and the 22nd in a plausible orchestration by Kirill Umansky). Several of these are first and only recordings (Nos 1, 3, 8, 13, 16, 20, 22), and for others the only rival is long since out of print (Nos 18, 19). I have to single out No 13 on Naxos (12/18) for the sheer heroism of the Siberian State Symphony Orchestra in tackling one of Weinberg’s most challenging scores. Kudos, too, to the Siberian Symphony Orchestra and Dmitry Vasiliev for giving us the Six Ballet Scenes (1973-75), also known as Choreographic Symphony (Toccata Classics; coupled with Symphony No 22), a piece that restores something of Weinberg’s 1958 ballet The White Chrysanthemum (to a maudlin post-Hiroshima tale), which never made it to the stage and may never have been orchestrated in full (surviving only in piano score). The add-ons in the Six Ballet Scenes are horrendously difficult, but are of special interest for their unexpected intersections with the style of Schnittke.

The only genres conspicuously underrepresented in the Weinberg discography are his songs and cantatas

Where choice exists, it’s worth seeking out Kondrashin for Symphonies Nos 4, 5 and 6 (Nos 4 and 6 on Melodiya, 12/06), which are probably the first to go for anyway, since they represent Weinberg at an early peak of his symphonic powers; and Barshai in Nos 7 (with both sinfoniettas on Melodiya) and 10 (most recently coupled with Kondrashin’s No 5 on Melodiya). At the moment it is hard to find these other than as downloads. On CD, the Chandos alternatives are more than decent, while for No 10 Kremerata Baltica is superb (ECM). The coupling of Symphonies Nos 2 and 21 by the Kremerata Baltica and the CBSO with Mirga GraΩinyt˙e-Tyla on DG has attracted loud plaudits, not just from me in these pages. We’ll see whether this breakthrough onto a major label heralds a step change for Weinberg orchestral recordings.

All six of his concertos, plus two concertinos and a fantasia for cello and orchestra, are represented in high-quality recordings too numerous to mention. The two flute concertos are helpfully coupled with the Clarinet Concerto and the Cello Fantasia on Chandos (9/08). The classic Soviet accounts of Weinberg’s Cello Concerto (Rostropovich), Violin Concerto (Kogan) and Flute Concerto No 1 (Alexander Korneyev) are on Melodiya, though again currently as download only. The finest version of the Trumpet Concerto (played by Dokshitser) is in the above-mentioned three-disc Melodiya chamber music set, which is in my selected discography; this is in many ways the most distinctive of Weinberg’s concertos, and Håkan Hardenberger is about to take it into his repertoire. Don’t forget the delectable Violin Concertino (as on the Kremerata Baltica set with Symphony No 10 and various chamber works) and the recently rediscovered Cello Concertino, which Weinberg later expanded to form the Concerto, played by Tarasova on a Northern Flowers disc (12/18).

Operas and vocal music

Weinberg’s seven operas (eight if you count the operetta The Golden Dress) are returning to the stage at varying rates. He regarded The Passenger as his most important work, and Shostakovich described it as a masterpiece. See and hear it for yourself on the DVD/BluRay of Pountney’s Bregenz production, which has since travelled the world. This production has its problematic aspects, but overall it is overwhelming and much to be preferred to the Yekaterinburg staging (Dux DVD, 9/18).

For entry-level Weinbergians, his last opera, The Idiot (completed in 1987), after Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel, is harder going. Its drama is more interior and slow burn, but in many ways it’s just as crucial as The Passenger to an understanding of the composer’s personality, in that the central figure of Prince Myshkin shares some of his core character traits of empathy, vulnerability, naivety and the urge to see good in all human beings. Kudos to Thomas Sanderling for masterminding the wonderfully performed Mannheim production, which in 2013 constituted the world premiere of the full-length version and which was recorded live in 2014 for Pan Classics.

The House of Opera website lists in-house recordings of Weinberg’s comic opera Lady Magnesia, after George Bernard Shaw’s send-up melodrama Passion, Poison, and Petrifaction; and his psychological tragedy The Portrait, based on Nikolai Gogol’s tale of an artist’s fateful sell-out to fame and fortune. These made-to-order recordings are no more than basic soundtracks, but the works themselves are again crucial to a rounded picture of the composer’s interest. Here’s hoping for commercial issues – preferably less heavily cut in the case of The Portrait – in the future.

The only genres conspicuously underrepresented in the Weinberg discography are his songs and cantatas. At least the austerely impressive Requiem is available – in a live recording from Bregenz (Neos, 5/12). This Soviet response to Britten’s War Requiem is a sternly uningratiating score, but again vital to an understanding of Weinberg’s ethical outlook. As for the songs, the three opuses out of a total of thirty announced as ‘Volume One’ by Toccata Classics (1/09) in 2008 are all winners, and the performances, especially of the wonderful Op 13 Jewish songs, are excellent. Private recordings of other song collections are tantalising indications of the riches that have yet to find their way to CD.

Conspicuous Gaps

The language barrier is surely one main reason why the songs are so sparsely represented. Weinberg’s closest tie to his homeland was through the poetry of Julian Tuwim, which he turned to for no fewer than seven of his song collections, a cantata and two of his symphonies. Singers are gradually rediscovering the power and beauty of these settings, but I look in vain for signs of CD companies queuing up to record them. The Ninth Symphony is an equally conspicuous gap. This magnificent succession of Tuwim songs, orchestrated and arranged for choir, derives from collections that Weinberg had not been able to publish and the title Lines that Have Escaped Destruction evidently refers both to his ‘rescuing’ of his own songs from oblivion and to Polish culture having survived Nazi depredations. This is not one of the tougher symphonies to perform. So why have we not heard it? Partly because it would take a massive investment to prepare the materials, but partly also because Weinberg chose to frame the settings with a Prelude, Interlude and Postlude apostrophising the Soviet role in liberating Poland. He may well have been unaware of the atrocities committed by the Red Army in that process, and he would probably have been disinclined to believe it, had he been told – and may have calculated that without such framing the symphony would be unperformable in the Soviet Union (it still awaits its world premiere). Whatever the case, those added texts make performance in present-day Poland problematic, to put it mildly.

For much the same reason, it is not easy to see how, despite some wonderful music, his second opera, The Madonna and the Soldier, could be restaged without radical producerly intervention, given that it is premised on the supposedly comradely fellowship between wartime Polish villagers and their heroic Red Army liberators. Perhaps the as yet unperformed Symphony No 11 will be heard at some point, despite its dedication to the Lenin centenary and some extreme difficulties for the orchestra; likewise, the less demanding No 15, to solidly conformist texts and composed for the 60th anniversary of the October Revolution, which more or less vanished after its premiere. Such rehabilitations would greatly complicate Weinberg reception, which for the time being draws sustenance and justification from the painful circumstances of his life. But maybe when the time is riper, that complication will be a necessary thing.

This article originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue – subscribe today!