Inside Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony

Gramophone

Wednesday, November 18, 2015

Conductor Manfred Honeck shares his radical thoughts on the work with Philip Clark

Manfred Honeck wants to clear something up about his new CD of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony: ‘This is a live recording. In fact, it was my debut with the Pittsburgh Symphony in 2006. I had to ask myself, would a new studio recording have been better? But no, I thought the chemistry between myself and the orchestra is incredible here. I was very happy to have it released.’ Listening to the recording, I hear a deeply personal Tchaikovsky Fifth: rethought, uncluttered, kicking against perceived wisdom. ‘Well, people say we have to interpret it in a Russian way, but my question is, what does this mean? Listen to the recordings of Gergiev, Mravinsky or Svetlanov and there are worlds between them – so what is Russian?’

Honeck answers his own question by dropping me deep inside the score. ‘Traditionally the finale is considered the most difficult movement,’ he asserts. ‘What to do? It’s loud and it gallops towards the last pages. But that’s not true. If you take time to properly work out the folkloristic elements, a different piece appears. There are hidden subtleties: the strings during the first four bars are marked forte, then, only in bar five, Tchaikovsky moves to fortissimo; in the first four bars the section leaders play, then Tchaikovsky introduces all the strings in bar five. Balalaika bands work in the same way – a small group, then it’s like 20,000 balalaikas are playing.

‘Tchaikovsky introduces this strange, nasal sound on the horn. It’s a warning that not everything in life is beautiful’

‘I became fascinated in this reference to balalaikas. Twenty bars later, the woodwind have this same “balalaika” material, but normally you can’t hear it because of the long notes in the strings and syncopated figures in the French horns. So I changed the dynamics. I felt it was right that the woodwind should echo what went before. Later, before the recapitulation, there’s a 30-bar transition section which Tchaikovsky marks più animato and then, suddenly, tempo primo. The tradition is to slow down through the transition and then jump suddenly into the tempo primo; which is fine, except that’s not what Tchaikovsky wrote. I go quicker through the transition, and by doing manfred Honeck produces a deeply personal Fifth that suddenly a Russian dance appears. It tends to sound like Bruckner or Brahms otherwise, but observing what Tchaikovsky writes produces a typical Russian dance style – the sort of music played on a balalaika.’

Gluing the symphony together is a melodic sequence, sketched out during the opening moments, that recurs in various emotionally pent-up guises throughout. I wonder how Honeck deals with the apparent danger that this so-called ‘fate motif’ could be perceived as a theatrical, not a musical, gesture? ‘The music must do it,’ he explains. ‘When the motif appears as the climax of the second movement, Tchaikovsky makes a personal statement – “I cannot live like this”. He writes triplets, then quavers, and puts accents on the quavers to emphasise: there is nowhere the intensity of feeling can go now.

‘In the Andante cantabile there is a similar sense of “We dance but this can’t be reality.”’ He’s talking about the second movement: French horn drizzled over supporting strings, usually a melt-in-the-ear window of release after the uneasy first movement. Not here. ‘The French horn is muted; why would Tchaikovsky want that? I think it’s because he wanted the horn to be a disturbing element. It’s a comfortable Russian dance. Everything seems so nice. But he introduces this strange, nasal sound on the horn. It doesn’t fit. It’s a warning that not everything in life is beautiful. There’s something coming.’

And what comes at the end might astonish some. Most conductors broaden the final few bars but Honeck does the opposite. ‘The only reason to broaden the tempo is to give the symphony a heroic ending. But Tchaikovsky’s markings indicate that, no, the tempo must be quickened. He didn’t want to have an overly confident ending. But thinking about the rest of the symphony, why would he?’

The historical view

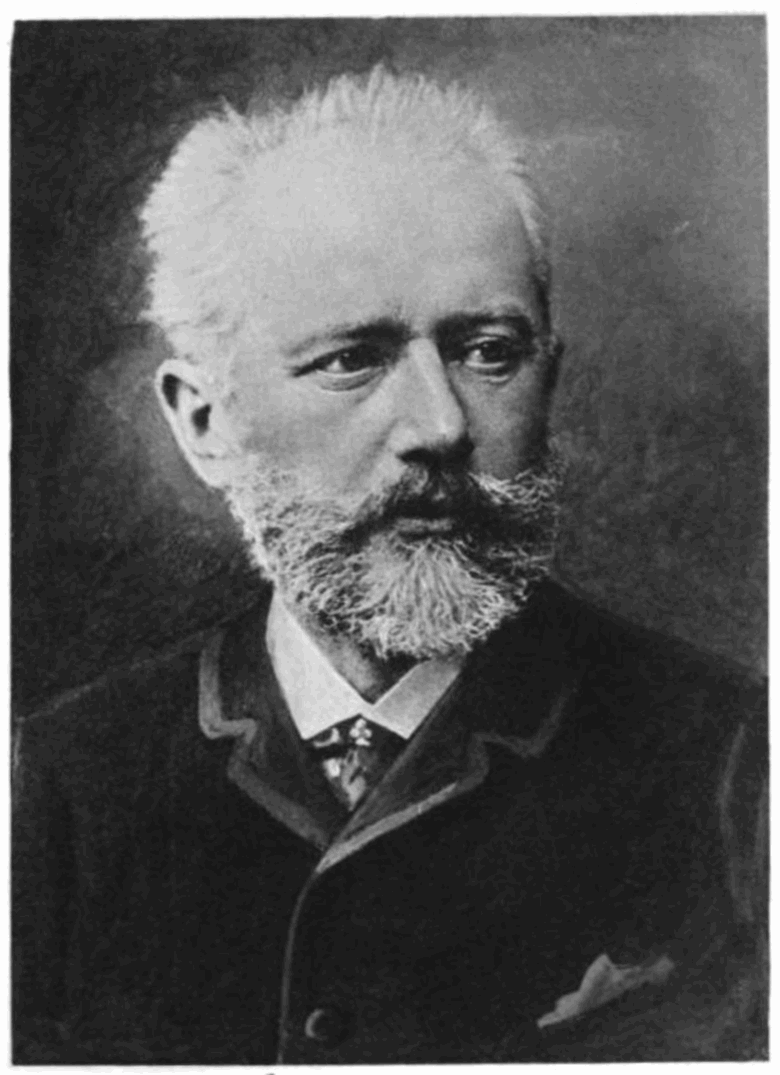

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Letter to patron Nadezhda von Meck (c1888)

‘I have become convinced that this symphony is unsuccessful. There is something repulsive about it, a certain excess of gaudiness and insincerity, artificiality. And the public instinctively recognises this. The ovations I received were directed at my previous work.’

Compton Mackenzie

Gramophone editorial (May 1939)

‘In Constant Lambert’s handling of the Fifth Symphony of Tchaikovsky I seemed to detect a deliberate attempt to put it in its place. I could almost have vowed that he had rapped with his baton the knuckles of the first violins to warn them against indulging in the slightest display of emotion.’

Valery Gergiev

Interview on Carnegie Hall’s website (2011)

‘The Fifth is maybe the most perfect symphony Tchaikovsky ever composed. You don’t expect Beethoven symphonies to take you to a theatrical world; but in Tchaikovsky you immediately imagine costume, colours – it makes you think immediately of theatre.’

This article originally appeared in the December 2011 edition of Gramophone