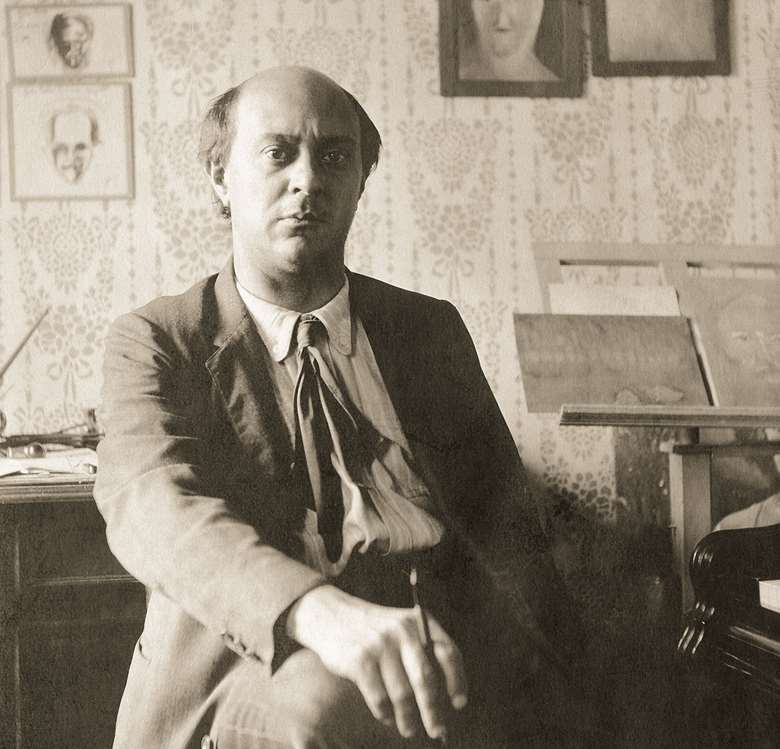

Impressions of Schoenberg: celebrating the composer at 150

Peter Quantrill

Friday, June 14, 2024

How should we view the composer whose music still divides audiences 150 years after his birth? Peter Quantrill and key Schoenberg advocates set his work in the context of his own era, and of ours

Register now to continue reading

Thanks for exploring the Gramophone website. Sign up for a free account today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Free access to 3 subscriber-only articles per month

- Unlimited access to our news, podcasts and awards pages

- Free weekly email newsletter