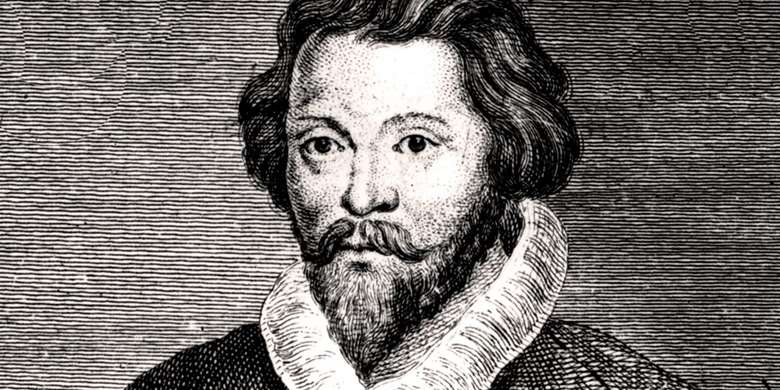

How William Byrd's music continues to inspire composers and musicians 400 years after his death

Tuesday, June 27, 2023

Ahead of a 12-day BBC Radio 3 celebration of the music of William Byrd, leading composers of today reflect on what his work means to them

Nico Muhly

Every time I listen to Byrd’s music, either for pleasure or for study, I am struck by how he moves so elegantly between passages of enormous complexity and then simplicity. The counterpoint is finely wrought and unimpeachably crafted; then, suddenly, the ear lands on a moment of harmonic simplicity which has a heart-breaking and intense effect. Byrd always seems to be walking the razor-thin edge between craft and heart, proving that the two can coexist. For me, this is hugely in evidence in Infelix Ego. Towards the end, multiple lines of counterpoint dissolve, and, after a moment’s pause, six glorious chords chime out on the word ‘Misericordiam’. It’s as dramatic a moment as you can find in any opera, and so beautifully crafted.

Gabriel Jackson

I’m a huge admirer of William Byrd, of course but, to be honest, his music has not had the same influence on my work as that of previous generations of English composers. My favourite Byrd piece, which I’ve loved since my chorister days at Canterbury Cathedral, is his perfectly formed little masterpiece Justorum animae, especially the gently descending scales at ‘in pace’. When I made my own setting of Justorum animae a few years ago I quoted that scalic figure, slowed down, and it always amuses me how so many experienced choral singers fail to notice that.

Roxanna Panufnik

In 2015, conductor Suzy Digby OBE asked me if I would write a Byrd-inspired piece for her new super-choir, ORA. My son had just become a Westminster Abbey chorister so Byrd’s extraordinarily beautiful music was only just really becoming known to me. As I studied his Five Part Mass, I was struck by how quickly and suddenly he would transpose and was happily surprised at his radical (for his time) harmonic changes. My favourite piece is his Ave Verum Corpus – the false relation on the word ‘misere’ still catches my breath, even though I know it’s coming.

I also hugely admire his courage at sticking to his Catholic guns despite living in a time of brutal persecution for being of the ‘wrong’ faith (a Catholic in the time of Protestant Elizabeth I). I’m about to start work on a new Byrd-inspired harpsichord piece, commissioned by the London International Festival of Early Music for Jane Chapman.

Harry Christophers

I first encountered the music of Byrd when I was a chorister at Canterbury Cathedral; one piece stuck in my memory, his rarely performed Christmas anthem This Day Christ was born. I loved it; little did I know that 60 years later I would find out that it came from his last publication Psalmes, Songs, and Sonnets which we recorded during the Covid years – for me, one of the few good things to come out of that dire time.

Byrd’s music is extraordinary – often incredibly complex, always inventive and emotionally challenging. If there is one piece I could not do without, it would be the two section motet Ne irascaris / Civitas sancti tui. Its brooding text is so powerful, at times intensely stark, on occasions sumptuous and then closing with 54 entries of the words “desolata est” where weariness and desolation abound simply staggering.

Brett Dean

The music of Byrd which first caught my attention, perhaps unsurprisingly, was the remarkable perfection and range of expression in his vocal music. Hearing the Mass for Four Voices live in Ely Cathedral was a truly awakening experience. More recently I’ve been increasingly enthralled by the keyboard music such as found in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Books. To the qualities found in his vocal music comes a significant contribution to the ‘liberation of the keyboard’ – in the words of Mahan Esfahani. Through his feel for the virtuosic capabilities of two spirited and agile hands, he proved to be a genuine pioneer in the field. The dramatic variations on the Elizabethan-era Catholic protest tune ‘Walsingham’ is a favourite.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad

It's so hard to choose my favourite piece by WIlliam Byrd, but certainly the one I know the best is O Lord, make thy servant Elizabeth. I was commissioned to write a piece in response to this work, and in preparation for writing, I played his work through endlessly on the piano, copied it out by hand twice, notated every single 'verticality' (every chord that ever occurs, including the dissonances created by passing notes and suspensions) and sang all of the individual lines repeatedly. I was particularly inspired by Byrd's final Amen, with the long held A flat in the top line symbolising devotion and constancy: in my version, the Amen is stretched to over two minutes in length, with the organ providing the 'pedal' note at the very top of the orchestra.

Kieran Brunt (Shards)

I’ve known Byrd’s work for as long as I’ve been a musician, really, and vividly recall singing Ave Verum Corpus at school; how the quiet intensity of the alto and tenor singing ‘…miserere mei’ would hit every time. It’s those moments of raw emotion, paired with the obvious technical beauty of the polyphonic writing, that remain the most transportive for me. Byrd obviously had such a deeply emotive connection with the texts he chose, writing as a devout Catholic under persecution from Protestant rule. The ‘Jerusalem motets’ - in particular Ne Irascaris Domine and Civitas Sancti Tui - stand out to me as such heart-breaking, political pieces of composition.

Georgia Ruth

Growing up, I played recorder and so Renaissance music played a huge part of my life for many years. Despite this, though, I never got the chance to play any of Byrd’s music! I’m so glad that I was given a chance – via BBC Radio 3’s Unclassified programme – to explore his work.

I was drawn to ‘The Bells’ – mostly for its title, which intrigued me. As I listened, I was struck by how the piece sounds both of its time, and inherently modern. Perhaps it has something to do with the very literal way Byrd uses the dynamic range of the harpsichord to recreate the pealing of bells. I loved how he sets the theme – so simple and beautiful – and then elaborates upon it: always layering, always building, to create something that hits you in full stereo! There’s a confidence and a joyfulness in the composing – as if he’s revelling both in his own ability and the possibilities of the instrument. This was so inspiring; the idea of limiting yourself to one instrument and seeing how far you can take it.

It reminded me of a fantastic Welsh triple harp piece – Clychau Aberdyfi (the bells of Aberdyfi) – which uses the harp’s three rows of strings to create a mesmerising pealing effect.

Laura Cannell

The music of William Byrd is embedded in my musical DNA; throughout my teenage years I played arrangements in recorder consorts and dance tunes in medieval banquets before studying the recorder at music college.

I love the sweet, dark, melancholy within the music. The contours and polyphonic suspensions ebb and flow in the most magical heart clutching ways. Byrd’s music feels like a really old friend, it makes sense to me even after years apart, when we meet, it feels crucial to my life. My current favourite piece by William Byrd is Retire My Soul (the track I recently re-imagined for BBC Radio 3’s Unclassified). When I hear it or read the score I am in a dreamworld of beautiful raw emotion.

Byrdsong, a celebration of Byrd’s music, runs on BBC Radio 3 from Saturday, July 1 to Wednesday, July 12, embracing such shows as Record Review, Music Matters, The Early Music Show, Essential Classics, Composer of the Week, Free Thinking and Choral Evensong, while on July 6, Unclassified: Byrd Reworked will see artists including Kieran Brunt and Georgia Ruth reimagine his music for today.