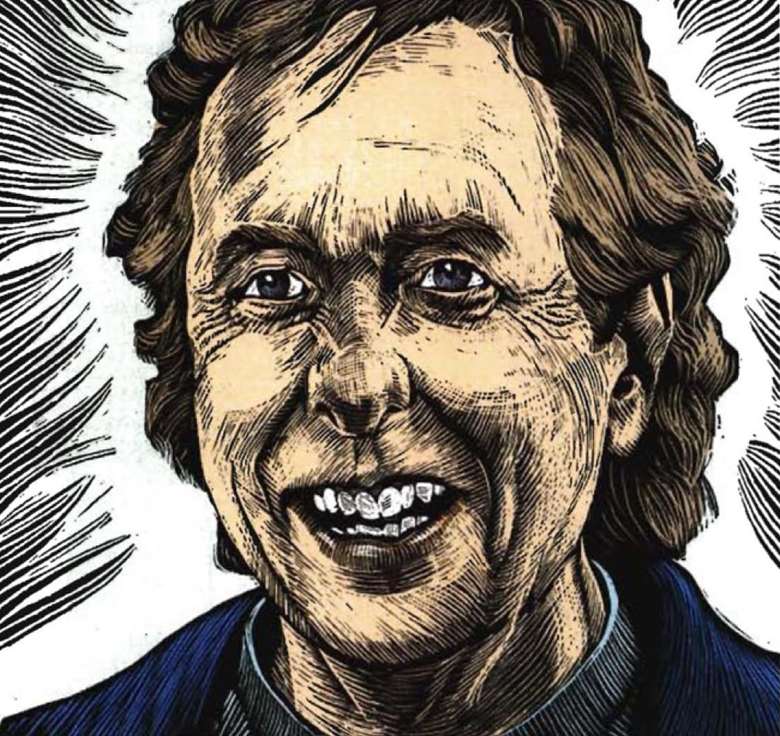

Eric Idle | My Music: ‘At a time when everything is aiming for superficiality, classical music shows the bravery of not compromising’

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

‘We Pythons were first in a field with TV comedy so we could go anywhere we liked. It was much harder for those who came afterwards’

For my generation, music first touched many of us in the forms of Elvis, the Everly Brothers and their like. When that late-1950s wave went away, I discovered classical music and jazz. Then The Beatles came along and it was OK to like pop music again. But the love of classical stayed with me, and I listen to 90 per cent classical music all day and have done most of my life.

At school in Wolverhampton they had a good collection of recordings, which was a lifeline – boarding school being a brutal place for me. The only thing about an unhappy childhood is that it can give you so much better a life. I learnt to retreat into my head and music became an escape, a way to fill all those hours. I can cope with almost everything now, including, I should think, prison.

‘There's so much that tickles you and very little in the world that actually moves you. That's what is so reassuring about classical music; it doesn't have to be funny’

Early loves included Brahms and of course Gilbert and Sullivan. Many years later, playing Ko-Ko in The Mikado at English National Opera changed my life. The director Jonathan Miller gave me my second career when he asked me to update the lyrics of Ko-Ko's patter song. At a stroke I became a musical comedy writer.

I love that form. Immediately I finished The Mikado I knew I wanted to write a musical. Musical comedy had died; it had become all about helicopters and big effects – MTV theatre. There was a cultural void waiting to be filled.

One idea I had in the 1980s was to tum Mel Brooks' film The Producers into a musical. I would have played Bloom, Mel himself Bialystock and Jonathan Miller would have directed. But Mel finally declined; he was devoted to making movies at the time. It was when I went to see his stage version of The Producers years later I knew I could sell Spamalot. The audience just went 'yes!' – they realised that they'd been missing this vital thing called laughter.

Sullivan remained my inspiration. Spamalot is very much a musical written by a Ko-Ko. Sullivan himself was always funny; his Ivanhoe period only came late on when Queen Victoria wanted him to get serious. In that first flush of his talent, when he first partnered Gilbert, he had that wonderful sense of a lightness of touch. He had great tunes in his head, and as a lover of Schubert also had a natural sense of how melody should work.

Cleverly, Sullivan doesn't give a nudge and a wink the entire time. It's a constant balance between light and darkness – and that's very Dickens, a very Victorian strain. I find in my shows that you can get very close to real emotion and still be moving. It isn't just parody. When one character sings about being alone in Spamalot, people have actually cried, but yet they can see it's funny.

Similarly, 'Always look on the bright side of life' is a war song at heart. The Monty Python team inherited that genre, it's what we came in with – 'The White Cliffs of Dover'. We just put inverted commas around it, and lo and behold, it becomes funny! Now, ironically, ours has actually become a wartime song; it was sung in the Falklands on HMS Sheffield, and then in the Gulf War.

There's so much that tickles you and very little in the world that actually moves you. That's what is so reassuring about classical music; it doesn't have to be funny. It gets to places that are deeper. At a time when everything is aiming for superficiality, classical music shows the bravery of not compromising. Art is finally about putting your feelings on the line.

That said, each musical form lasts about 80 years. Jazz does that, rock'n'roll does that and the symphonic form does that. After that time, you reach the limits of what you can explore and of course the freshness and freedom of being first into a field is gone. We Pythons were first in a field with TV comedy so we could go anywhere we liked. It was much harder for those who came afterwards.

I'm about to combine comedy and music again with a Handel-style oratorio based on The Life of Brian, entitled Not The Messiah (He's A Very Naughty Boy). We're doing it, conducted by my cousin Peter Oundjian, at the Caramoor and Toronto festivals. It jumps into different classical genres and whole realms of fun, with numbers like 'Hail to the shoe'. The idea is to attract a different crowd back into the concert hall.

This article originally appeared in the August 2007 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue of the world's leading classical music magazine – subscribe today