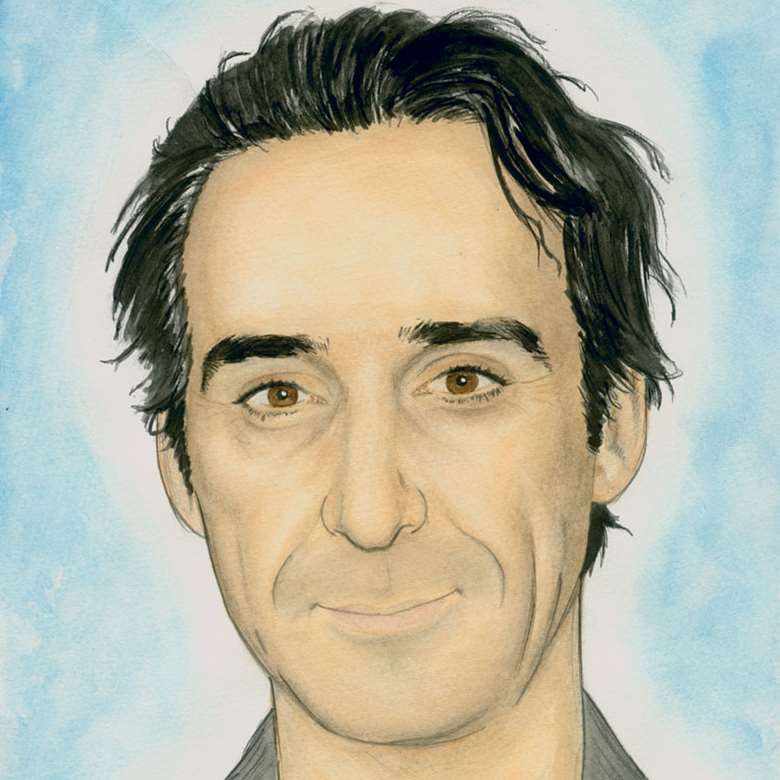

Alexandre Desplat | My Music: ‘At their best, film scores are real music, not background wallpaper, and can work equally well in a concert hall’

Gramophone

Monday, February 20, 2017

Alexandre Desplat on finding the balance between fiction and function

I always dreamt of being a composer and, more specifically, a film composer. I was less interested in writing contemporary concert music but instead wanted to combine my joint passions for cinema and music. I started my musical education as a flautist and although the flute is a wonderful instrument, I began to feel limited, so started to play a number of different instruments while fantasising about having an orchestra of my own.

The great thing about film music is that it encompasses such a wide range of cultures and styles, and by gathering this palette of colours and expressions you begin to find your own musical voice. Thus, between the ages of 13 and 20, I would listen to everything I could, day and night. I was dripping in music – from jazz to bossa nova, to Ravel, Debussy, Shostakovich, Messiaen and Boulez. Every kind of music was rich and different and exciting. In this way I started to discover a musical vocabulary of my own.

‘The best directors, such as Stephen Frears and Roman Polanski, understand that cinema is a collaborative art and is therefore something you have to share’

Young people often ask me how they can become a film composer but they must understand that film music ultimately serves the movie. This means that you must be interested in cinema and prepared to meet directors and editors – to speak less about the music and more about the actors and photography. So this is what I did. I began by writing a lot of music for the stage and one of the actors in a Shakespeare production of mine had directed a short film, so he asked me to compose the music for this. More short movies followed and eventually my first feature. It was a long process but a satisfying one.

I have had the opportunity to work with some fantastic directors throughout my career. The best directors, such as Stephen Frears and Roman Polanski, understand that cinema is a collaborative art and is therefore something you have to share. The biggest test is to challenge directors, because they want you to surprise them, to open windows and gates they have never considered for their film.

Most important is finding the balance between function and fiction. Function will ensure that the music fits well into the mechanics of the film but fiction enables you to tap into the invisible – the deep psychology, pain and notions of the characters. It has a very special strength but only works when balanced equally with function, because the music cannot be detached from the story.

No matter which film you are dealing with – large or small – the process is fundamentally the same. I recently wrote soundtracks for the latest Harry Potter and for The King’s Speech, and the main difference between these was the amount of music required – over two hours for Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 1, and less than an hour for The King’s Speech. Obviously Harry Potter comes from a lengthy franchise, with music originally written by John Williams, so you are part of a piece of cinema history. But in the end it comes down to you, locked away in a studio, scratching your head and trying to come up with ideas quickly because the director will be there in an hour.

Music for film can often be overlooked by the classical community and for this reason it drives me crazy when I hear a bad score at the cinema. There will always be someone who says, “See, I was right. Movie music is bad!” At their best, film scores – like the kinds I listened to in my teens by Herrmann, Waxman and Steiner – are real music, not background wallpaper, and can work equally well in a concert hall. Of course, we film composers must be humble, because our art is part of a larger process, but although I hear a lot of wallpaper, I always strive to write real music as much as I can.

This article originally appeared in the February 2011 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue of the world's leading classical music magazine – subscribe today