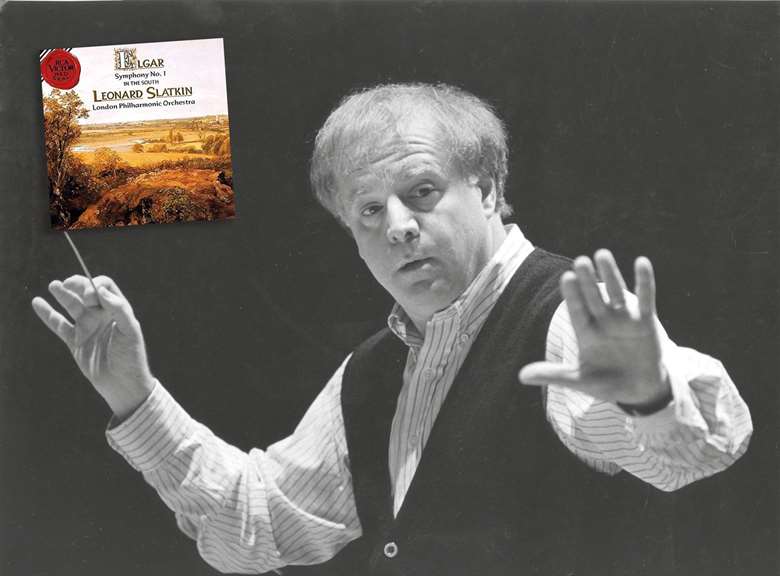

Classics Reconsidered: Elgar Symphony No 1 (London Philharmonic Orchestra / Leonard Slatkin)

Friday, February 21, 2025

David Gutman and Andrew Farach-Colton discuss Leonard Slatkin’s 1989 recording of Elgar’s First Symphony with the LPO

The original review

Elgar Symphony No 1

London Philharmonic Orchestra / Leonard Slatkin

RCA Victor Red Seal

Slatkin’s devotion to, and understanding of, Elgar is again impressively evident in his recording of the First Symphony. RCA have given him a richer, clearer sound than for his splendid interpretation of the Second (8/89). Like Menuhin, on his recent Virgin Classics recording, Slatkin stays nearer to Elgar’s own handling of this work. The brisk tempo of the second movement, for example, is very much in the composer’s own manner. The scintillating playing of the London Philharmonic in this movement makes it a virtuoso demonstration of Elgar’s skill as an orchestrator.

Where Slatkin brings his own view of the symphony most firmly into focus is in the first movement. Without in any way sentimentalizing the music, or pulling it about, he makes the listener – this listener, at any rate – painfully aware of its underlying note of tragedy. Some idyll of happiness seems repeatedly to be just eluding Elgar’s grasp – every time it seems he will reach it, it proves to be a mirage and vanishes. In the poignant coda, most beautifully played, he accepts that his paradise is lost. Only Barbirolli, in his earlier 1957 Pye recording with the Hallé (currently unavailable), brings home so touchingly the resigned despair of this movement.

The symphony’s Adagio, paradoxically, emerges in this performance as marginally less moving. Just why, it is hard to say. It is marvellously played, especially the interplay of oboe, clarinet, flute and bassoon, and there is a real ppp in the last six bars. But Slatkin, though only in the slightest degree, misses the ultimate atmosphere of the rapture with which this movement is enveloped. The finale, on the other hand, is totally satisfying. In all, a most distinguished addition to the Elgar discography. Michael Kennedy (6/91)

David Gutman This Leonard Slatkin recording was runner-up in the Orchestral category of the 1991 Gramophone Awards, but it’s Slatkin’s Second Symphony that I’ve long had on my shelves, presumably because it won more consistent acclaim this side of the pond. The First may not be a ‘classic’ in the usual sense of the term but it does receive a refreshing and, in several respects, distinctly ‘modern’ kind of reading. It’s never overlarded with rubato and is reluctant to swagger. I can see why you wanted to revisit it.

Andrew Farach-Colton Slatkin is at least partly responsible for my becoming a devoted Elgarian. I was a conducting fellow at the Aspen Music Festival in the summer of 1989, when Slatkin visited and conducted Elgar’s First on one of his programmes (this was just a few weeks before this recording was made). At that point, I loved the Enigma Variations and had heard the First on record but it hadn’t yet resonated with me. Attending Slatkin’s rehearsals and hearing him take the piece apart and put it back together, followed by an intensely passionate performance, left me absolutely obsessed with the work. I was overjoyed when this recording came out but agree that while it’s refreshing and even ‘modern’, it can now seem studio-bound at times.

DG That might be the miking more than the performance, but we’ll get to that later. In the first two movements, tempos are faster and/or more consistently maintained than was common at the time, although Elgar himself was no slouch, and Sir Georg Solti had attempted a famously brisk rethink also with the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1972. Many swore by the results, others found Solti as insensitive in Elgar as he was in everything else. The drive of Slatkin’s second movement is certainly ruthless. Then again, Elgar’s scherzos are often tauter nowadays, and that approach always excites me. It’s in keeping with the notation but also perhaps ‘unidiomatic’. What, I wonder, does that mean though?

AFC Slatkin’s tempos are at the extremes almost throughout. The introduction is quite slow, but then the Allegro has tremendous impetus. I’m a huge fan of Solti’s Elgar, actually, and the sense of nervous energy he captures, especially as it’s so like Elgar’s own recordings. Slatkin (who apparently made a point of not hearing any of the composer’s interpretations until he’d formed his own) takes the second movement even faster than Solti, and it may be pushed too hard. With that hair’s breadth of a difference, Solti conveys an appropriate sense of menace. That said, what I like about Slatkin’s approach is that it’s almost Mendelssohnian – a connection I hadn’t really considered before. Perhaps it’s idiomatic in that way, even if Elgar himself was far less mercurial in his own performance?

DG I can’t say Slatkin struck me as deft exactly – certain magical moments feel slightly wooden, but again the sonics may be a factor. Andrew Keener and Mike Hatch placed the orchestra further back than was customary in Walthamstow Town Hall, although the sound roars into life once you turn the volume up. There’s often surprising clarity and linearity in places where listeners might be accustomed to a pea-souper blend. Brass punch through more abruptly than in the ‘warmer’ string-heavy EMI recordings of Sir Adrian Boult or Sir John Barbirolli. They’re mostly able to do what is asked of them too, in a way that was probably impossible in Elgar’s day. Did the band have difficulties at Aspen?

AFC Absolutely, and I’m sure the score was brand new to almost all of the Aspen players, as one rarely encounters Elgar’s symphonies stateside. I agree the balance here isn’t ideal; I far prefer the in-your-face sound Decca provided for Solti in those halcyon analogue days. Still, I think the LPO strings fly through those long streams of semiquavers rather deftly indeed, and with thrilling results. My one real disappointment is the Adagio. It’s slow, yes, but I think the issue isn’t so much about tempo as it is about a lack of frisson; it’s precisely where the performance seems studio-bound. Bernard Haitink with the Philharmonia is just as leisurely but with an expressive magic that keeps my rapt attention. Does it fall a bit flat for you, too?

DG I think a certain short-term flexibility is lacking. You sense the conductor keen to derive his moves from the score rather than the tradition, but when he does admit an inflection ‘from the outside’ it sounds momentarily Mahlerian. The pluses include some very beautiful and some very soft playing. Might that different ‘feel’ even be a good thing?

AFC I agree about the soft and beautiful playing, but I never sense Mahlerian leanings. Tradition is such a curious concept when it comes to Elgar, particularly as his own recordings were never treated as interpretative templates in the supposedly good old days.

DG Yes, and of course the anomalies go further. There’s nothing local about this music – it was, as we know, strikingly successful internationally in its early years. Then, in no time, it’s as if everyone is embarrassed by it. Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor in The Record Guide of the early 1950s eviscerate the whole Edwardian era: ‘Boastful self-confidence, emotional vulgarity, material extravagance, a ruthless philistinism expressed in tasteless architecture and every kind of expensive yet hideous accessory: such features of a late phase of Imperial England are faithfully reflected in Elgar’s larger works and are apt to prove indigestible today.’ This is not to say that the authors doubted Elgar’s genius, marvelling as they did at the way the substance of the First Symphony’s scherzo is transformed into that of the Adagio at a fraction of its original speed. Slatkin tackles the piece very much that way, as an abstract symphonic entity. Or at least that’s how I hear it.

AFC Point taken, and perhaps conductors like Slatkin, Solti, Haitink and others outside the English tradition weren’t freighted with those prejudices. From today’s perspective, I find this performance most compelling in the two outer movements. I agree with Michael Kennedy that Slatkin makes us painfully aware of the opening movement’s ‘underlying note of tragedy’, with happiness always just out of reach. And I find the finale similarly moving. I get a real sense of a fight for one’s life. Note the sense of inexorable motion at figure 126 (around 5'50"), and how even in the final two minutes or so the battle still rages around us. Even the victorious end feels precarious.

DG Cards on the table. I prefer Sir Colin Davis at his subjective, singalong best in concert with the Dresden Staatskapelle in 1998 (Profil, discussed as part of Replay, 3/24). Davis offers a different realisation of ‘massive hope’ at the close, the victory grander and more velvety but to my ears more meaningfully contested. With Slatkin, I hear the formal rounding off of an overly stiff, somewhat protracted discourse. That said, part of my problem is that Elgar’s splashes of colour are undersold by that normally ultra-reliable sound team. Take the episode in which Elgar transforms his slightly militaristic idea into a soaring vision at half the speed. The harp arpeggios seem dulled. And weren’t you put off by the dispiriting thud of the timpani? I did like the way those vaguely Wagnerian depths are coloured at the start.

AFC The distant perspective certainly robs the sound of its necessary oomph. Davis’s Dresden recording was made live, so it has that tension that’s ultimately missing in Slatkin’s interpretation. I should add, putting my own cards on the table, that I was greatly disappointed with Davis’s awkward LSO Live account, but while the German performance has some distracting fussiness here and there, it’s convincing and emotionally potent taken as a whole.

DG Last time this work was the subject of a Gramophone Collection (8/19), older recordings with foreign connections mostly fared badly. Davis’s Dresden version – my favourite despite missed entries and woozy sound – was passed over. So too this altogether straighter, Anglo-American take.

AFC An increasing number of foreign conductors now dip their toes into Elgar’s music. What’s special about Slatkin, I think, is that he’s all in. I’m eternally grateful that he brought his zeal to a largely student orchestra in Aspen decades ago – that changed my life, at least. Is this performance a ‘classic’, or even an ideal representation of his Elgarian bona fides? Maybe not, but taken in the context of the RCA box collecting all of his Elgar recordings, I’d say Slatkin’s insights and deep affection make it well worth a hearing.