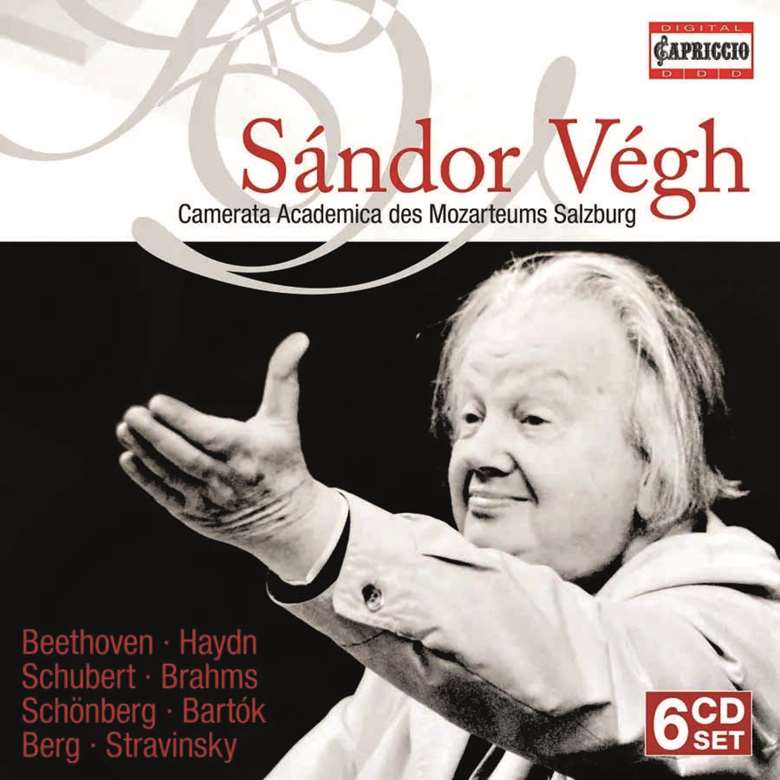

Box-set Round-up: January 2025 (Sándor Végh, René Jacobs, Beethoven: The Mahler Re-Orchestrations)

Rob Cowan

Friday, January 3, 2025

Rob Cowan on a great Hungarian conductor and some symphonic surprises

Among the highlights of Capriccio’s newly reissued set in which Sándor Végh conducts the Camerata Academica of the Salzburg Mozarteum are major chamber works writ large for orchestra, Brahms’s great G major String Quintet (Op 111) being especially successful. Those intoxicating first few bars – a chamber equivalent to the Third Symphony’s inspired opening – launch us into the midday sun. Like his older colleague Pablo Casals, Végh is both forceful and lyrical, with an impeccable sense of rhythm and spontaneity always a given. Four Schubert symphonies (Nos 5, 6, 8 and 9) benefit from Végh’s rustic approach, and it goes without saying that this master of Bartók’s quartets (as leader of the Végh Quartet, twice recorded) makes hay with the composer’s dancing Divertimento, balancing Bartók’s concerto grosso-style forces with a perfect sense of aural perspective. While on the subject of quartets, Végh and his players upscale Beethoven’s Op 131 Quartet (and Grosse Fuge, both with Soloists of International Musicians Seminar), controlling dynamics while lending the music symphonic proportions: they fairly thrust the Fugue into action, holding the tension for the movement’s duration, while effectively enriching the textures of Haydn’s The Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross. A musician of lesser stature might have allowed these ‘orchestrations’ to sound overblown but such was Végh’s artistry that that never happens. We’re also given Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night, Berg’s Lyric Suite – both feelingly played – and an account of Stravinsky’s Apollon musagète that scores top marks for fire (in the Coda) and mystery (Apothéose). A remarkable collection, realistically recorded.

Végh’s muscular Schubert contrasts markedly with brighter, more transparent and more buoyant Schubert symphony cycles under the likes of Harnoncourt, Dausgaard and de Vriend, now joined by the B’Rock Orchestra under René Jacobs – a set of performances which, although nurtured within the period-performance tradition, is original in detail and execution, the playing brilliant, elegantly turned and full of refreshing, even unexpected ideas. Take the Fifth’s Menuetto, which accelerates wildly towards its close (from 5'11"), or the stark drama of the Fourth’s opening. There are rhetorical pauses too, in the Fifth’s Menuetto and the Ninth’s Scherzo. Jacobs is generous in his observance of written repeats and his choices of tempo avoid the manic extremes favoured by some of his rivals (especially in the Ninth), though the outer sections of the Second’s Menuetto – which segues into an exhilarating finale – match anyone’s for excitement. If you fancy sampling, I’d suggest trying disc 2, which couples the Second and Third Symphonies. Among the best of the best, definitely. The Unfinished includes portions of narration dealing with parental influences (texts are available online). Kasper van Kooten explains.

The most interesting aspect of Beethoven: The Mahler Re-Orchestrations is that without having access to Mahler’s scores it’s often mere speculation as to which ideas are his and which are brought out by the conductor. Christoph Becher explains that Mahler doubled the winds, filled in some voices, cut others or transposed them by an octave, all in order to make the melody come through more clearly, which it invariably does, the timpani too (especially in the Ninth). It’s hardly surprising that the symphonies that best benefit from this treatment are the big odd-numbered works (Nos 3, 5, 7 and 9), all of which are scrubbed clean – though listen to recordings by Toscanini, Szell, Gardiner and others and the process of clarification works equally well without Mahler’s help (had he been around to record in the stereo era I doubt he would have bothered rescoring). Still, with good performances by the Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz under Michael Francis, the recordings are well worth troubling over. Various overtures are also included.

And from reorchestrations to a performing version of Tchaikovsky’s ‘Symphony of Life’ (or, as Eugene Ormandy would have it, the Seventh Symphony). Most familiar is the first movement, otherwise known in its guise as the Third Piano Concerto. The Russian State Cinematographic Orchestra under Sergei Sk∑ipka acquit themselves with all guns blazing, while recordings of the last three symphonies under Yevgeny Mravinsky (stereo DG), Nos 2, 3 and Manfred under Gennady Rozhdestvensky and a musical if rather more sober account of the First under Konstantin Ivanov are of exceptional quality. All these are Russian recordings, as is a superb Third Suite under Vladimir Jurowski. Other highlights include the Violin Concerto with David Oistrakh (and Ormandy conducting), Richter, Karajan and the VSO in the First Piano Concerto and Gilels under Kondrashin in the Second. A real Tchaikovsky‑fest, this, musically rich and mostly distinguished, performance-wise, in generally good stereo sound.

The recordings

Bartók. Beethoven. Brahms. Schubert. Stravinsky, etc

Camerata Academica of the Salzburg Mozarteum / Sándor Végh (CapriccioC7422)

Schubert Complete Symphonies

B’Rock Orch / René Jacobs (Pentatone PTC5187 353)

Beethoven The Mahler Re-Orchestrations

Staatsphilh Rheinland-Pfalz / Michael Francis (Capriccio C5484)

Tchaikovsky Complete Symphonies, etc

Various artists (Alto ALC3)