Box-set Round-up: November 2024 (Prêtre, Celibidache, Jansons)

Rob Cowan

Friday, November 1, 2024

Rob Cowan on the legacies of a trio of conductors in the music in which they excelled

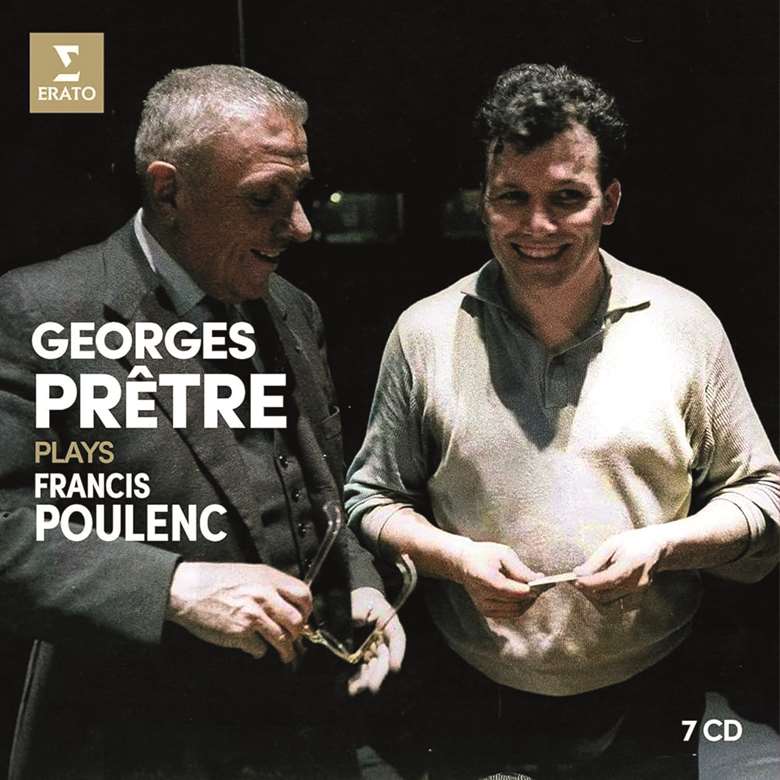

The French conductor Georges Prêtre, whose birth centenary we celebrated in August this year (he died in 2017), studied harmony under Maurice Duruflé and conducting under André Cluytens. Two boxes have appeared commemorating Prêtre’s art, the first from Erato, bringing together recordings that he made for the label between 1959 and 1988 of music by a composer he was especially associated with, Francis Poulenc. Prêtre gave the premiere of Poulenc’s opera La voix humaine at the Opéra-Comique in 1959 and conducted the first performance in France of his Sept Répons des Ténèbres in 1963. Both works are included in the set, La voix humaine with Denise Duval, Répons with the Maîtrise de la Sainte-Chapelle. Among other compositions featured are the concertos for one and two pianos (with Gabriel Tacchino in both and Bernard Ringeissen in the two-piano work), the Organ Concerto (with Duruflé), Concert champêtre (with Jean-Patrice Brosse, harpsichord), two versions of The Story of Babar the Elephant (with Peter Ustinov, narrating in French and English), Stabat mater (with Barbara Hendricks) and numerous other works. Various orchestras are involved, mostly from France, though there’s a cracking version of the delicious ballet with singers in one act, Les biches, with the Ambrosian Singers and the Philharmonia. Prêtre seemed to relish Poulenc’s mischievous – and often miraculous – mix of wit, rhythmic élan and occasional visits to darker climes. The transfers are excellent and so are François Laurent’s booklet notes. Irresistible.

In 1996 Prêtre took over the creative direction of the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, and our second Prêtre box brings together a wide range of mostly live recordings dating from between 1994 and 2004, the majority made in the sympathetic acoustic of the Liederhalle Stuttgart. Some performances are tailed by applause, others not, but all shed fresh light on Prêtre’s considerable talent. Six symphonies – including Beethoven’s Third, Brahms’s First, Dvořák’s Ninth, Bizet in C and Bruckner’s Fourth – are flexibly handled with plenty of excitement, though in each case the slow movement is a highlight. Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique is fired with temperament, the first movement especially (and note the dramatic timps in the ‘March to the Scaffold’). Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé Second Suite is about as close to perfection as we’ve a right to expect, from the burbling winds at the beginning to the wildly racing ‘Danse générale’ at the end. La valse also packs a punch or two (as does ‘Kashchei’s Dance’ from Stravinsky’s 1919 Firebird Suite), though Mahler’s Todtenfeier (which was to become the first movement of the Resurrection Symphony) doesn’t quite hit the target. Respighi’s Pines and Fountains of Rome draw on Prêtre’s vivid sense of orchestral colour, as do Richard Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel, Don Juan and Der Rosenkavalier Suite. All in all, an enjoyable Prêtre centenary showcase, very well recorded.

At the opposite end of the interpretative extreme from Prêtre is Sergiu Celibidache, most specifically with the Munich Philharmonic. In Celibidache’s hands (we’re talking 1993) the last two movements of Bruckner’s Eighth Symphony play for a mere seven minutes less than Eugen Jochum takes for the whole symphony (same edition, on his 1964 DG recording). But given the sustained intensity of Celibidache’s readings, timing is almost an irrelevance. Got to 23'45" in the Fourth Symphony’s finale, where Celibidache turns the accompaniment into a marching figure and the music becomes a triumphant arrival … inspirational is the word (unrecognisable too, maybe). No one else’s reading is even remotely similar. Atsuo Fujita’s ‘overtone reconstruction’ remastering for hybrid SACD improves on anything we’ve had before, and in addition to Symphonies Nos 3‑9, we’re also given the F minor Mass and the Te Deum. Detailed commentary is of little use. The thing to do is listen, to allow the Bruckner/Celibidache symbiosis to carry you away (the conductor considered ‘Bruckner’s existence as God’s greatest gift’), which it will do, trust me. An interesting extended rehearsal for the Ninth (in German) is also included.

A fascinating English-language rehearsal for Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony (surely his greatest?) involving the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra under Mariss Jansons factors in the human, cultural and political issues that faced Shostakovich and the Russian people during wartime and helps explain the symphony’s sense of terror. This is an excellent cycle (recorded 1988-2005) that calls on the skills of various first-rate orchestras (including the VPO, BPO, LPO, Bavarian RSO, Oslo PO, Leningrad PO and Philadelphia Orchestra) and includes various extras, not least excellent accounts of the two piano concertos with Mikhail Rudy and the cello concertos with Truls Mørk. Jansons’s experience with his highly gifted conducting father Arvīds, not to mention the great Mravinsky, ‘rubbed off’ (so to speak) and the least one can say about this fine-sounding set is that it carries the authority of ‘being there’. Certainly recommended by me.

The recordings

Poulenc Georges Prêtre (Erato 5419 79937-8)

The SWR Recordings Georges Prêtre (SWR Music SWR19155CD)

Bruckner Symphonies, etc, Sergiu Celibidache (Warner Classics 2173 22485-5)

Shostakovich Symhonies, Mariss Jansons (Warner Classics 5419 79571-7)

This article originally appeared in the November 2024 issue of Gramophone. Never miss an issue – subscribe today