Mahler's Symphony No 2, by Mariss Jansons

Gramophone

Thursday, January 1, 2015

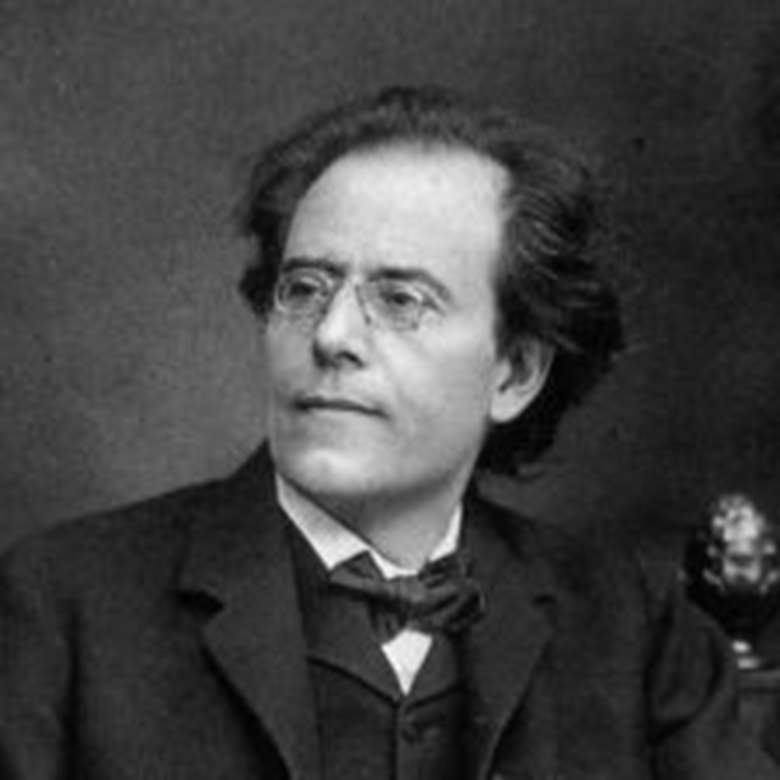

Mahler is one of the most significant composers in the world, in all of history. The questions he sets out in his works are enormous. Why is his music so popular? It’s because in his music there is everything. It’s universal. You find nature, sarcasm, love, hatred, the grotesque, tragedy and comedy. Like finding his own face in a mirror, every listener can find something to relate to, a bridge into the content of the music. There is something for everyone – and people find echoes of their own fears, doubts and suffering.

The Second Symphony is typical of how he puts for himself and for listeners the big questions. What is life? Why are we living? What will be next? Is there an afterlife? The piece questions a lot, then he describes the mood of the human soul and in the last movement he answers the questions he raises in the first movement. His answer is the Auferstehung – the resurrection – because he believes we live many, many lives. That first movement is a funeral march for the hero of the First Symphony and that heroic element is very typical of Mahler, in almost all his symphonies. Who is the hero? Man, Mahler himself. In this respect Shostakovich is very close to him, for Shostakovich is another composer who represents himself as the hero in his own music. Mahler never observes from a distance. He is 'inside' every situation. He wrote at the time that he imagined himself in his own coffin. Then we go through the moments of life. The second movement recalls nice, beautiful moments. These are nice memories. The third movement raises more philosophical questions. It’s based on Mahler’s own song about St Anthony of Padua preaching to the fishes, which of course is really addressed to human beings. The movement is full of phantoms and darkness. The fishes listen, then they forget. They don’t learn. This is Mahler’s view of human beings. The conclusion is that you can tell people what you want. You can preach, you can tell people how to live, what not to do, but the reaction is nothing. Satire, sarcasm and irony are there in the form he used, and Mahler believed only a few people would understand his message.

The conclusion is very modern. In the 21st century our technical development is so advanced and our scientists have achieved so much, so our spiritual development too should be at such a very high level, but the development of the heart and soul is far behind. People can fly to the moon but spiritually they are at a low level, because we don’t learn from our mistakes and we don’t take care of our spiritual development. It’s interesting that he should put such a light melody – almost a street melody – into such a serious and philosophical symphony, but that is typical of his use of the grotesque. In the fourth movement, 'Urlicht', we are dealing with very deep music from the soul, and the love of God. This should be sung in a childlike voice, to capture the innocence and pure soul of a child. This was Mahler’s credo – true honesty can be found in how a child reacts. The fifth movement is an incredible fantasy. There is a frightful, terrifying march of the dead, then comes the big call – God and judgement. This is – or should be – the softest entrance by a choir in all musical literature. The chorus speaks with God and prays, with a special optimism. Here is the answer. Everybody is waiting for God’s judgement, then it doesn’t happen. In that movement, everyone is equal. There is no judgement in the end for him. Everything is calm. This is very special – you are in another world already, and you start a new, different life, like a child. Such music could only be written by a genius and only Mozart could compose this quickly.

The latest edition from Universal corrects another 500 or so mistakes. There are instances where it is possible Mahler himself made a mistake, which every human being can do. There is no clear evidence either way and only Mahler could have given a definitive answer. Even in Beethoven there are mistakes and my old teacher used to say 'we don’t correct this, because we are happy to repeat the mistake of a genius'. It’s really important to establish what Mahler really wanted, but he was polishing this symphony right up until the last performance he gave of it, in Paris in 1910. We can take account of the changes he made but with Mahler there are no ultimate answers.

Interview by Michael McManus (Gramophone, March 2010)

Explore Mahler's symphonies with the leading Mahler conductors:

Symphony No 1, by Charles Mackerras

Symphony No 3, by Lorin Maazel

Symphony No 4, by David Zinman

Symphony No 5, by Simon Rattle

Symphony No 6, by Christoph Eschenbach

Symphony No 7, by Valery Gergiev

Symphony No 8, by Michael Tilson Thomas

Symphony No 9, by Esa-Pekka Salonen