Inside Bartók's Solo Violin Sonata

Rob Cowan

Friday, February 5, 2016

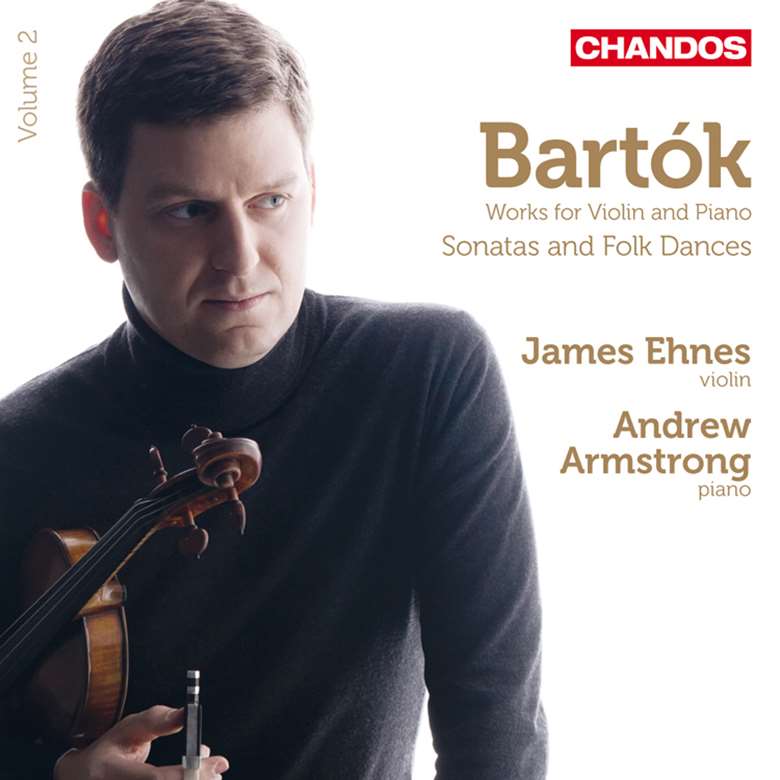

Rob Cowan talks to violinist James Ehnes about the demands of Bartók’s Solo Violin Sonata

James Ehnes joins me over coffee to discuss one of his abiding passions, the music of Béla Bartók. Ehnes and Bartók share at least two characteristics, a quiet manner and a caring though not over-literal respect for the letter of the score. How does he square his sensitive musical instincts with the indications on the printed page? Just suppose that the two don’t tally. Ehnes is unequivocal: ‘There’s always a reason why an indication is there,’ he tells me. ‘If I can’t justify my interpretation as being the best way of bringing those indications to life, then I feel I’m missing something crucial enough that I maybe need to take a little more time to figure things out.’ He sees the score as a roadmap for getting to a specific musical destination and confirms that different composers use notation in very different ways. He says that if you take an approach that’s both too literal and too consistent, you can end up getting yourself into trouble. So ‘tempered freedom’ might be his credo.

Ehnes’s latest recording opens with one of the cornerstones of the 20th-century violin repertory, Bartók’s Solo Violin Sonata, written to a wartime commission from Yehudi Menuhin. He’s fascinated by various extant textual sources, including the original manuscript, emendations that Bartók and Menuhin cooked up between them, and Peter Bartók’s Urtext of 1994 (published by Boosey & Hawkes).

We leaf through this Urtext, looking at where – in the closing Presto – passages involving quartertones are printed beneath the less colouristic alternatives, ‘colour’ being Bartók’s primary reason for using quartertones in the first place. But some of the most striking chordal passages are in the other movements, for example bar 44 in the first movement (2’49’’ into track one), which is one of those instances where if you play it the way it’s written you basically have to forget what you’ve been told about concepts of hand shape and traditional technique.

Getting your head around bars 40-42 (2’35’’–2’45’’), really hearing those harmonies and intervals clearly – that’s another challenge. From a purely violinistic standpoint, Ehnes has learnt so much by playing this piece. Take for example the trills in bar 83 of the fugue (3’12’’ into track two): here he had to contort the hand in a way that’s pretty uncomfortable but that proved useful when later on he was playing solo Bach and needed to use the same type of hand contortion. The educating process of recording Bartók over the last few years has revealed to Ehnes many passages of extraordinary delicacy, ‘and to be honest, that’s where you sink or swim. A lot of the swashbuckling Bartók will work just great, guaranteed. It’s hard to mess up the Romanian Folk Dances. But a movement such as the Melodia from the Solo Violin Sonata or the slow movement of the First Violin Sonata should draw the listener into a world that’s so personal as to be even a little uncomfortable. That for me is the real challenge of a movement like this…and certainly the Melodia’s middle section [poco più andante, 3’06’’ into track three] is technically very uncomfortable for the hand. With many of these tremolos, particularly the wider ones, if your hand isn’t really strong then it starts to create accidental harmonics, a kind of whistling – weird and…unsuccessful.’

The CD includes Hungarian and Romanian folksong arrangements, ‘entry-level, user-friendly Bartók’, says Ehnes, ‘pizza-pieces – meaning that even when they’re bad they’re still pretty good! Some kid in a competition performs them and gets everyone all fired up, even if they’re not especially well played.’ An amusing thought, though not one that Ehnes’s playing will prompt. That much I can guarantee.

The historical view

Malcolm Gillies – The Bartók Companion (1993)

‘While in Asheville, North Carolina in 1944, Bartók allowed the experience of Menuhin’s Bach performance [C major Sonata, BWV1005] to mingle with his own compositional ideas…The fugue from the Sonata for Solo Violin was Bartók’s ultimate offering as a contrapuntalist.’

Yehudi Menuhin – Menuhin: A Life (Humphrey Burton, 2000)

‘I regret that I was not able to let him [Bartók] hear it in a truly finished interpretation, for over the years the music has come to speak to me, and I believe all of us, in the deepest musical terms…[The fugue] was perhaps the most aggressive, brutal music I was ever to play.’

Béla Bartók to Menuhin – Unfinished Journey (Yehudi Menuhin, 2001)

‘I am rather worried about the “playability” of some of the double-stops, etc. On the last page I give you some of the alternatives. I sent you two copies. Would you introduce in one of them the necessary changes in bowing[…] and also indicate the impracticable difficulties? I would try to change them.’

This article originally appeared in the January 2013 issue of Gramophone.

Visit Gramophone's Reviews Database to read the review of James Ehnes's recording.