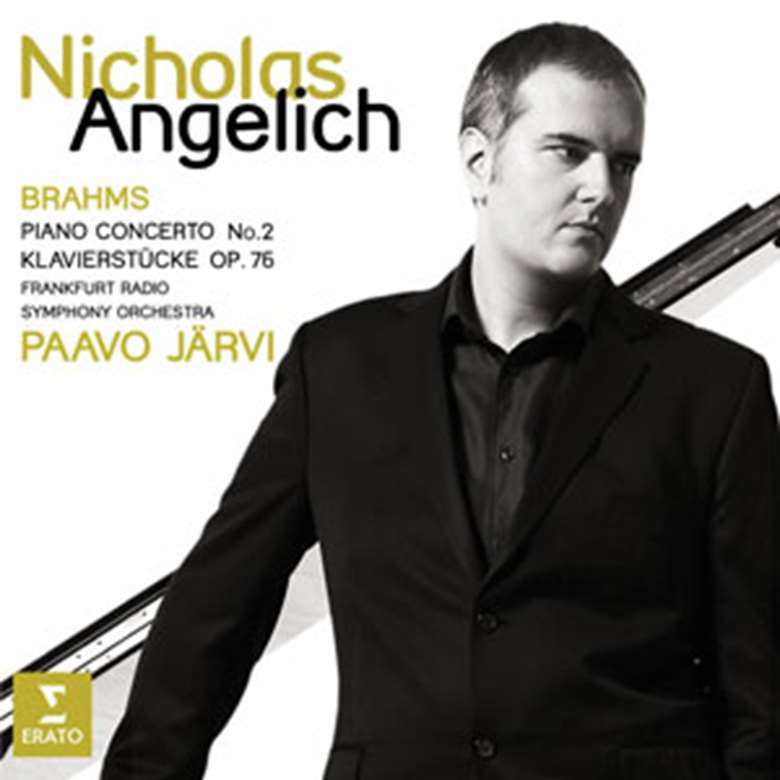

Brahms Piano Concerto No 2, by Nicholas Angelich

Gramophone

Monday, September 5, 2016

The American-born, Paris-trained pianist on Brahms’s ‘symphony with piano obbligato’

When I was a student at the Paris Conservatoire, I started by learning this piece, not Brahms’s First Concerto. Many people were more attracted initially to the latter, maybe because it has a typically Romantic feeling about it, a dramatic gesture. Perhaps it often appeals to younger, or maybe even not so young, performers because there is this dark Romantic quality to it, this terribly tragic atmosphere around it: the whole connection with Schumann and his suicide attempt, and all the incredible emotional outpouring, the reaction to all of this. And, of course, it feels like the music of a younger man – which may be a simplistic thing to say, but I really think there is a kind of quality there that might be more instantly appealing. Right from the start it is completely new and experimental.

The Second Concerto (written more than two decades later) is experimental too, but it’s a bit more complicated. I was more attracted to it because I had listened to it much more at home with my parents. I was very familiar with it and had several recordings I really loved. The one I loved the most was by Wilhelm Backhaus – it was a huge source of inspiration and joy.

There’s a subtle kind of maturity in the way that Brahms expresses himself in the piano-writing, in how he constructs the piece and in the orchestra’s interaction with the piano. As I said, this piece’s character is very different from that of the First Concerto: it’s a completely different universe in terms of sound, emotions, inspiration – everything.

My teacher, Aldo Ciccolini, wanted me to play the Rachmaninov Third. I started working on it, but it didn’t interest me at all at the time. When I asked him if I could work on this instead, he was apprehensive, thinking that this was more a piece for an older musician, with a more mature point of view, more experience in music and in life in general – but I stuck to my desires and my ideas.

Simple yet complex

Ciccolini was very demanding, but it was a great learning experience. It is of course an extremely difficult piece in peculiar ways because, pianistically, technically, the language that Brahms uses to express his ideas is very simple, but at the same time very complex, very difficult, very elaborate and very subtle. It’s a symphony, really, with piano obbligato; and it’s always important to have an understanding with the conductor. If you don’t have a good relationship, it’s very difficult because if you’re not happy with the tempo, if you’re not happy with something, there’s not really that much you can do. The piano is, of course, a very important element, but at the same time it needs to integrate into the whole structure, which is very difficult and makes the piece very different from other piano concertos. There is an incredible amount of interaction and you have to think about the unity. This can be very beautiful but, at the same time, it’s one of the most challenging aspects of the piece. There’s an incredible variety of things going on, but there has to be a sense of structure. This is connected with tempo, with many things, including sound.

The first movement has such incredible scope, and the way Brahms develops all of the thematic material is quite amazing. Then you have this second movement, where there is a very grand quality and, suddenly, this duet with the principal cello in the third movement – a beautiful moment of intimacy and peace which is so touching. There’s a lot of things like that going on in the other movements too, but this section really is a duet. It has a special quality. I also think it’s necessary, just in terms of having a moment of, not relaxing, but of gathering your energy and expressing things in a totally different way. It helps you. No matter how many times you’ve heard it, no matter how many times you’ve played it, it’s always so moving.

After everything that has happened musically, emotionally, in terms of the orchestra, in terms of the colours…After all of this, suddenly you have this last movement which does have depth, but which is also very light. There’s a dancing quality to it, and it has incredible grace and charm. There is also that beautiful Hungarian theme. You can feel these Hungarian and Viennese qualities; and the orchestration is so beautiful. It’s truly a masterwork – the focus here is about being playful, having fun.

Putting the music first

There are some very difficult moments in the whole concerto, and I think it’s important never to think of these as ‘virtuosic’. The solution is to think of things in a musical way – how do you make sense musically of something? It should obviously not be superficial, but when you’re just trying to understand pianistically how to do things better, you must think in a musical way. It should never be just about technique.

I made my recording with the Frankfurt Radio Orchestra and Paavo Järvi. He’s a wonderful musician, with a lot of humour. He’s very demanding and inspiring to work with. He had a clear understanding about details and, of course, about the structure and the sense of how to make things work. He’s an interesting musician. You need to have this kind of partnership with somebody you can really understand, who understands you and the piece, with whom you can build something momentous.

Explore more great piano concertos

Beethoven Piano Concerto No 5, by Paul Lewis

Grieg Piano Concerto, by Leif Ove Andsnes

Mozart Piano Concerto No 27, by Angela Hewitt

Prokofiev Piano Concerto No 3, by Jean-Efflam Bavouzet

Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2, by Stephen Hough

Ravel Piano Concerto in G, by Pierre-Laurent Aimard

Schumann Piano Concerto, by Ingrid Fliter

Shostakovich Piano Concerto No 2, by Alexander Melnikov

Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No 1, by Yevgeny Sudbin