Yunchan Lim interview: ‘I decided that I will give up everything for music’

Jeremy Nicholas

Monday, May 20, 2024

Yunchan Lim shot to prominence when he won the Van Cliburn competition at the age of 18. Now 20 and attempting to remain detached from his superstar status, he releases his eagerly anticipated debut album for Decca. Jeremy Nicholas meets him

There is footage on YouTube of Yunchan Lim playing Rachmaninov’s Third Piano Concerto in the final of the 2022 Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. So far it has been viewed more than 14 million times. As he storms to the work’s conclusion, there is a roar of approbation as the audience gives Lim a standing ovation. Unusually, instead of genteel taps of bows on music stands and a desultory stomping of feet, applause also comes from the orchestra. Look closely at the bottom right of the screen and you will see a cellist wearing a face mask who puts down her bow so she can raise her hands above her head to clap. You won’t see that very often.

This performance of Rachmaninov’s Third Concerto is one of those rare occasions when pianist, piano, conductor, orchestra and composer come together as one. Jean-Efflam Bavouzet said afterwards that he and his fellow jurors left the hall ‘in an ecstatic way – we didn’t talk, but our eyes said it all!’ Orchestra and audience knew they were watching a star being born.

Gramophone has followed Lim’s progress since the Van Cliburn, but perhaps his name has not registered with you yet, just another in the seemingly unstoppable procession of brilliant young Asian keyboard talents that have emerged in the past few decades. Lim is in another class. For once, you can believe the hype. His progress has been documented in a way that past generations of musicians cannot have envisaged, as performances that chart his rapid development have been filmed and uploaded to the internet. You can marvel at jaw-dropping accounts of Liszt’s Mephisto Waltz No 1, one when he was 15 and another when he was just 13. Close your eyes and you could be listening to Vladimir Ashkenazy, Boris Berezovsky or Evgeny Kissin, rather than a boy just into his teens. You might then alight on footage of him at 15 with a violinist friend in a practice room playing the final pages of Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto. They’re mucking about, exaggerating, having fun, but the passion, commanding technique and musicality (to say nothing of the trademark Beatles haircut that lends its own drama to proceedings) are all there.

You don’t have to be a piano connoisseur to realise that you’re in the presence of an exceptional musician. Most refreshing is his willingness to confound expectations

Above all, I recommend you follow his journey at the Van Cliburn. He embraces repertoire ranging from François Couperin to Sir Stephen Hough, and after every performance you will come away thinking, ‘Well, that’s about as good as it gets.’ But beware! To follow Lim on YouTube is to go down a rabbit hole: once you start viewing, it is very hard to stop (‘Well, perhaps just one more before bed’). The preliminary round saw him play the prescribed piece commissioned by the competition, Hough’s Fanfare Toccata, followed by some Couperin, a Mozart sonata (K311) and a sparkling account of Chopin’s Variations on ‘Là ci darem la mano’. For the quarter-final programme he presented the three-part Ricercar from Bach’s The Musical Offering, Scriabin’s Sonata No 2 and Beethoven’s Eroica Variations. So far so good. His semi-final concerto choice was Mozart’s No 22 in E flat, K482. Few will have heard it given with such delicate, understated simplicity – or with Edwin Fischer’s cheeky cadenzas.

What set the ‘pianorak’ world talking was Lim’s semi-final solo recital, given the night before. For this he had made the daring decision to play Liszt’s complete Études d’exécution transcendante. Here, everything was on display – virtuoso technique, tonal colouring (Lim seems to be incapable of producing an ugly sound), characterisation, risk-taking, lyrical repose, expressive rubato and, most unexpected in a competition setting, he was clearly having the time of his life: watch him in ‘Feux follets’, generally considered to be the most digitally and musically challenging of the set, and you’ll see what I mean.

After this, there was little doubt as to the winner. As I wrote in these pages (9/23) after that semi-final Liszt performance was released on disc, ‘This is, unquestionably, a great piano recording. In this young pianist’s hands you will hear one of the finest-ever performances of the 12 Transcendental Studies, and I include all those made in the studio or captured, as here, live in front of an audience without a safety net. To play this ferociously demanding music with such technical perfection and poetic insight in any concert performance is something, but to do so while taking part in the semi-finals of a major international piano competition is nothing short of miraculous.’

So to the final, which required two concertos, one Classical, one Romantic. First Lim played Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No 3, elegant, refined, stylistically assured with a palpable meeting of minds between soloist and conductor Marin Alsop. Then, as we have seen, came Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No 3, a work that is a personal favourite. It is a subjective judgement, of course, but for me Lim’s is one of the greatest performances of this concerto that I have ever heard. The ending moves me to tears every time I watch it.

‘Decca’s people came to many concerts and did their best to share their vision for my future and its evolution. I got fascinated with their passion, energy and interest’

Lim was born in Siheung, 25km south-west of Seoul in South Korea, as recently as 2004. This is the first Gramophone cover feature about an artist who was born in the 21st century. It was no easy matter setting up an interview with him, for having won the Van Cliburn – the youngest person to do so – with its $100,000 and world tour as first prize, he has since had, let us say, a hectic life. Everyone wants a piece of the action. In his home country he is a national hero, mobbed like a rock star wherever he appears, with fans wearing T-shirts bearing his image (something I am told he loathes). The fan pack issued in Korea as a taster for his debut album sold out before the album was released, an event which made the national news. Unprecedented.

We eventually meet via video link, he in Paris, me in the UK. It is the morning after his triumphant debut with the Orchestre de Paris and Klaus Mäkelä playing Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto. Conversation is conducted through a genial translator in Seoul for, at present, Lim speaks little English. He has done very few media interviews prior to this. Yunchan greets me silently with a bow and a wary smile. He is charmingly diffident, touchingly humble, and clearly does not relish this aspect of his chosen career. Even in his native tongue, he speaks hesitantly, economically and thoughtfully in a low monotone. It is, to be frank, not the easiest of encounters, with long Korean exchanges eliciting short answers in third-person English. Yunchan is an intensely serious young man whose sole aim in life is to practise the piano, get better at playing the piano, learn more piano music and play the piano in front of as many people as possible. Like the late great Nelson Freire, he is a very private person who has chosen a very public profession, a dichotomy with which few of us have to contend.

Recording at Henry Wood Hall in London: Yunchan Lim with record producer John Fraser (photo: Karolina Wielocha)

Liszt’s Transcendental Études (live from the Van Cliburn competition, released on the Steinway & Sons label as part of the competition deal) was Lim’s first solo album released in the West. What we are here to discuss is his first studio recording. This is for Decca, the label that won the race to sign him last year: Chopin’s Études, Opp 10 and 25, another audacious choice. Given that he seems to thrive in front of television cameras and an audience, why did he opt for a studio recording instead of a live event, perhaps from his performances in Amsterdam or his Carnegie Hall debut? ‘Of course, I admire all the live recordings of my illustrious predecessors, but for my debut album I wanted to increase the quality of my work, so I could make a lot of takes and choose the best of them. There were two other advantages. One: I could exclude all external barriers and really enjoy the chance to explore the different interpretative possibilities. Two: although I was confined in a studio, I had four days to make the recording, allowing me to focus on the music without interruptions.’ And why choose music that has been recorded many dozens of times before? ‘First, I wanted to tread in the footsteps of all the great pianists I admire. Second, it is my first album ever and I want to record the études as an announcement of this “epic” which is the journey of my musical life.’

Having explored Lim’s playing online (including a complete Liszt Années de pèlerinage – année 2: Italie from 2020, ending with a stunning Dante Sonata that threatens to spin out of control but doesn’t, Beethoven’s Fourth and Fifth Concertos, Rachmaninov’s Second, the Schumann Concerto, Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons, Chopin and hyphenated Bach encores), I guess that he is well acquainted with the pianists of the ‘golden age’ – the era of Hofmann, Levitzki, Horowitz and Rachmaninov. There’s tonal beauty, the ability to inhabit the music from within, the pure joy of music-making and willingness to add a mischievous little something of his own if he feels like it (there’s a clever octave rewrite towards the end of the Dante Sonata, for instance, and some doubled octaves in the finale of Rachmaninov’s Third Concerto). My guess proves correct, and Lim’s face lights up. ‘I first started listening to the great names when I was 13,’ he tells me. ‘My teacher recommended I listen to Friedman. I was walking home on my way back from school and I was electrified. Shocked. I just stood there on the road amazed by the freedom of the playing and then felt almost remorse about my own playing. That was the moment when I became determined to improve my playing. Vladimir Sofronitsky was another. So was Mark Hambourg. And Busoni playing Chopin. These pianists are maybe not so familiar to the general public, but I strongly recommend that young artists like me should listen to them.’

The teacher he mentions is Minsoo Sohn, making Lim the latest member of a particularly distinguished piano family tree: Sohn (Korean-American, born in 1977) was taught by the late Russell Shermann, who was taught by Eduard Steuermann, who was taught by Busoni – this lineage can be traced further back through Reinecke to Liszt and thence to Czerny and Beethoven. Sohn moved from Korea to study at the New England Conservatory, Boston, where he graduated in 2004. After holding positions at Michigan State University and the Korea National University of Arts, he joined his alma mater in the autumn of 2023. Lim has been studying with him since the age of 13 and has followed him to Massachusetts. ‘Minsoo Sohn and I have built a great trust between us for a long time,’ Lim says. ‘Mr Sohn is a great pianist and I became hooked on the way he plays the piano. I really love it. We know each other very, very well. The lessons I have had from him are more than great, and during those years I have felt no need to go to any globally prominent music schools.’

Hearing or watching this young man, just turned 20, you do not have to be a piano connoisseur to realise that you are in the presence of an exceptional musician. What is most refreshing is his willingness to confound expectations. Except for Liszt’s Liebestraum No 3, one of the encores, his UK debut at London’s Wigmore Hall in January 2023 eschewed the high-Romantic gestures that most people in the sold-out audience might have expected. He began with Pavana lachrymae, Byrd’s arrangement of Dowland’s song Flow my teares. Few of even the most assiduous pianophiles will have come across this work, but Lim thinks that ‘Byrd is the greatest of all British composers’. This was followed by Bach’s 15 Three-Part Inventions (or Sinfonias), BWV787-801, and Beethoven’s Op 33 Bagatelles – far from your standard recital fare, let alone from an 18-year-old making their London debut. Beethoven’s Eroica Variations completed the programme.

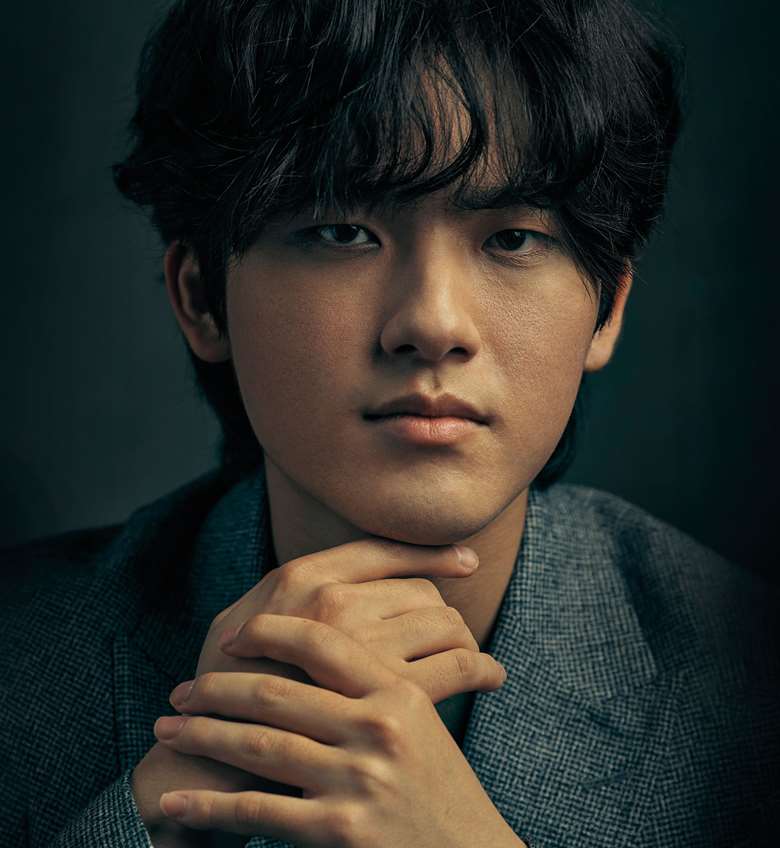

Yunchan Lim is a private person who has chosen a public profession (photo: Karolina Wielocha)

Having described how ‘the sighing phrases of the Dowland were transmuted into subtly coloured, immaculately voiced arcs’, and admired the ‘imaginatively dispatched’ Bach miniatures, one London critic in his five-star review praised ‘the range of moods explored in Beethoven’s Eroica Variations, where Lim’s virtuosity was at its most dazzling, yet as always deployed so as to highlight the idiosyncratic exuberance of the music.’ Quite right. But, having reported that at the end of the recital ‘virtually the entire audience rose excitedly to its feet, mobiles held aloft to capture the young star’s image’, this reviewer concluded: ‘Lim could well prove to be the Lang Lang of his generation.’ True, he may be able to inspire his fellow Koreans to take up the piano in the same way that Lang Lang has done in China, where it is said tens of millions of people now play the instrument; he may well earn the huge sums of money that have allowed Lang Lang to become a musical philanthropist. I hope so, but I doubt it. The diffident Lim is on a different trajectory. At this point of his career, celebrity status bothers him. He is also a far more refined and sophisticated musician: his address of the keyboard, economy of gesture, impassive face and quiet hands are marks of high quality. And, of course, there are none of the physical mannerisms and illustrative gurnings that are so much a feature of the colourful Chinese superstar’s performance persona.

The concert was streamed online. John Gilhooly, artistic and executive Director of Wigmore Hall, revealed in these pages (9/23) that it had had a million views. ‘We offered to take it down as per the contract with [Lim] but he said, “No, leave it up.” He wrote to me directly and said, “I want it there because it was a very good concert.” So obviously a young person sees that as part of his brand. And that opened up a whole South Korean audience to us on online, but I also noticed that coming through in visitors when they’re in London. So you’ve an audience that comes just for the pianists, and they’re selling out.’

I asked Lim about his childhood – his family, the place where he grew up. The response was not illuminating. He remembers very little. He was just ‘told to go out and play’. There was a piano at the ‘local teaching centre’ which he took to, and his mother instigated piano lessons when he was seven. Only then did the family purchase a piano for their home. Just a year later, he participated in his first competition. In an interview with my colleague Jed Distler for International Piano magazine (July/August 2023) Lim revealed that ‘the piece I played in that competition was Chopin’s Waltz in B minor, Op 69 No 2. At that time, my first teacher, Ms Kim Kyung Eun, recommended that I listen to recordings by Evgeny Kissin and Sergey Rachmaninov. Looking back now, it seems like starting my musical life with Kissin and Rachmaninov was a divine intervention.’

Who, I wonder, first told him that he had a special talent that needed nurturing in the right way? ‘Nobody. I realised myself that I needed education and training at the age of nine. In Korea we have the Music Academy of Seoul Arts Center, which has courses for talented children and I auditioned for that and was accepted.’ I wonder how he will cope with this apparent conflict of having a public career and a private life. I had read that he had a fantasy of buying a log cabin in a remote mountainous area. ‘You can translate that in two ways,’ he says. ‘One is actual – but not right now! The other is a metaphor expressing my long-term goal in music. That can be directly related to my career and the number of concerts I choose to play.’ At the moment, he tells me, that amounts to about 60 a year.

As for future recording plans, he’s not saying. There will be one concerto album, one solo, but he’ll need Decca’s approval before he discusses the matter. Why did he choose Decca? ‘First, because of the sound quality. It’s the best in the world. Second, because their people came to many of my concerts and did their best to share their vision for my future and its evolution. I got fascinated with their passion, energy and interest in my concerts.’ Does he have any time for hobbies? ‘No,’ comes the translation. ‘He puts greater value on appreciating the great pianists and practising the great composers. He sees that activity as very cool. Very cool. And that’s how, as a young person, he wants to spend his time at present. So no hobbies.’

Speaking at a press conference after the 2022 competition, Yunchan said, ‘I made up my mind that I will live my life only for the sake of music, and I decided that I will give up everything for music … I want my music to become deeper, and if that desire reaches the audience, I’m satisfied.’ It’s a noble aspiration. To say he has made a good start is an understatement.

Read the review: Chopin Études (Yunchan Lim)

This article originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of Gramophone magazine. Never miss an issue – subscribe today